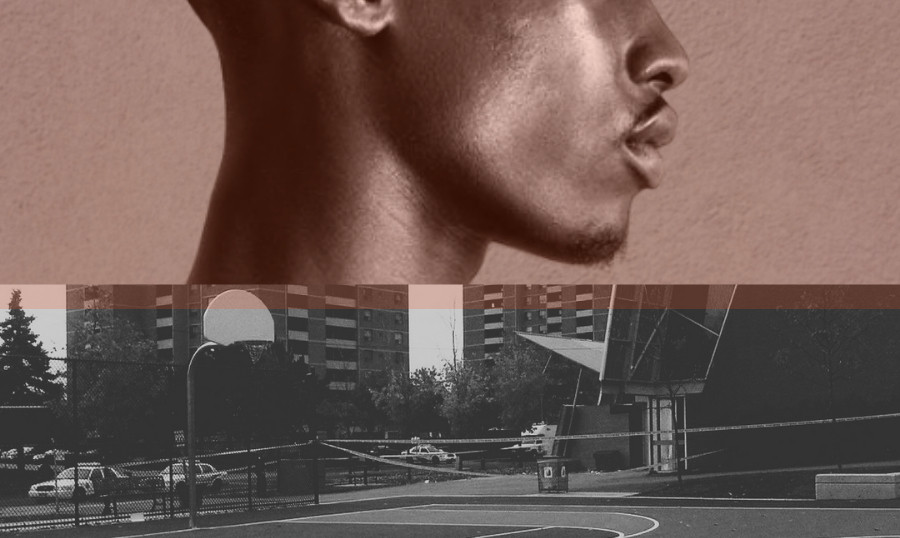

Approximately 600 murders happen in Canada each year with 232 murders in Ontario. African, Caribbean or Black (ACB) individuals account for 44% of the homicides despite accounting for only 4.7% of the population.

Researchers like Dr. Tanya Sharpe, Founder of The Center for Research & Innovation for Black Survivors of Homicide Victims (CRIB) and Associate Professor at the University of Toronto, are better positioned to explore this challenge on a deeper level. She currently holds the position of Endowed Chair in Social Work in the Global Community at the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work.

“I always refer to myself as a community-engaged researcher,” she said. “What that means to me is that the community will always tell you what it needs if we just turn our ear to listen.”

Dr. Sharpe is one of a few researchers doing this kind of community engagement work on gun violence in academia. This shortage of researchers has led to a lot of anecdotal evidence but minimal data. These researchers are working hard together to bring stories from the community to the academy and public consciousness.

One of the outcomes of this collaboration has been a framework developed by the CRIB on the Social Determinants of Homicide. It organizes information around the gun violence that has steadily been on the rise, and brings language to the structural root causes that lead to this violence.

Every victim of gun violence is someone’s child. Behind each pulled trigger of a firearm is also someone’s child. The research estimates that each homicide victim leaves at least seven to 10 family members and/or close friends struggling to cope with the violent and tragic death.

The report, researchers, and advocates highlight the need to attend to the structural violence that precedes any of the gun violence that happens in communities. The structural inequities that occur in the education, housing, justice, media, entertainment, employment and healthcare systems, create violent barriers that impact families on a consistent basis. The structural poverty that often results from many of these systems, leads to outcomes that disproportionately impact the lives of the communities most likely to be involved in alternative economies that include gun violence.

Connecting the dots

“It's not a coincidence that the same neighborhoods that are disproportionately impacted by homicide are the same neighborhoods that are disproportionately affected by Covid-19,” said Dr. Sharpe.

The same structural inequities that have led to the disproportionate health outcomes that preceded Covid-19, are the same structural inequities that have led to the disproportionate numbers of death and loss related to the virus in Black communities.

Many saw Covid-19 as a catalyst for solutions developed over the last two years. The blatant disparities of Covid-19 deaths in Black communities, in addition to the murder of George Floyd by the police, brought more attention to the longstanding challenges of structural racism and its reality. A tidal wave of support came rushing in to begin to remedy some of the problems.

“They’ve moved the world for Covid,” said Paul Bailey, Executive Director at the Black Health Alliance.

“Moving to address gun violence is simple. There just has to be commitment.”

Community leaders are working with government and decision-makers to ensure funding for systems that deliver community care and programming are made available to better serve communities in need of support.

“Responding to gun violence means that we have a coordinated and collaborative environment that allows us to work effectively together, police can't do it alone,” he said.

Leaders propose systems modeled off American programs like Ceasefire and Safestreets that are doing the peacekeeping work of interrupting violence in communities.

These programs employ credible community messengers, who have either lived in communities that have experienced high rates of gun violence, both fatal and non-fatal, or who have themselves been involved in criminal activity, transformed their lives, and want to invest in making sure that youth don't make some of the mistakes that they've made.

Conditions, culture, & coping

It’s difficult to have a conversation about gun violence without having a conversation about a culture that frequently glamorizes and promotes it. Hip-hop culture and the products sold for profit therein, play a huge role in both coping and profit-making strategies that are dominant in communities impacted by gun violence. Some of the products sold and promoted under the umbrella of this culture, include violent music, drugs, and sex.

The rapper Killer Mike has been quoted saying that “Hip Hop is today’s Blues.” In a city with gun violence steadily on the increase over the last few years, there’s plenty of Blues to go around.

“Especially in the 2022 Hip-Hop era, gun violence is the number one trend,” said Marlon Morgridge, Father, Artist, and Youth Worker at Weston Frontlines.

“People like violence. People like to see people get hurt, but don’t actually want for it to be them,” he said.

The true underbelly of Street Life is the direct opposite of glamorous. It is a dark and dangerous industry. Many of those active in the lifestyle look forward to the chance to retire from it. The alternative economy and life of crime may look cool and attractive to those on the outside, but for those inside, it’s a constant cycle of survival mode.

“It’s a lot of smoke and mirrors,” said Morgridge.

“It's kind of attractive when you hear somebody talking about doing this and that and seeing the confidence, especially in the music videos. But a lot of these artists haven't even done this stuff,” he said.

“They may have experienced it, saw it around, had a friend that went through it, and they’re that voice for those people as an artist, to paint that picture.”

The music attracts a lifestyle, and the pitfalls of that lifestyle follow its artists. Artists are expected to live up to their lyrics which leads to men, adversaries, and authorities seeing them as a target. What began as a form of expression, representation, and potential income, quickly becomes a signed contract into a dangerous and lonely lifestyle.

“Anybody who may carry a gun, they’re feeling power. The thing in your brain is you have something to defend your life and, if you use that on anybody, you're in control of that person's life, not them.”

For a group of people living on the margins, and off the books, this externalized sense of control and security can be empowering. In many cases, this tool can be perceived as the only opportunity at gaining a feeling of being in control. Particularly for young men in a competitive, oppressive, and expensive city, where power is not easily attained. This illusion is only further inflamed by the facade of social media.

“It’s a trap--pun intended,” warns Toronto artist, Juice.

Juice is a Hip-Hop artist, and experienced a dose of success with his single Mopstick. The song glamorized gunplay and the bravado of the downtown fast life. After doing some soul searching as someone who identifies strictly as an artist, he came to realize he didn’t like that his music was instigating and promoting murder and that from a business perspective, it was limiting.

“There’s only so far you can go with that kind of content,” he said.

“People wanted me to keep making that kind of music, but it wasn’t really what I wanted to create. If you get stuck doing that music, it’s hard to climb out into real views because that’s your audience and box, and it’s a small box,” he said.

Since his single, he’s pivoted to making music about life that speaks to more people, not just those who are involved in criminal activity, or those who like to watch it from the safety of their screens. He believes there needs to be a resurgence of true artists, and he aims to be one of them.

Morgridge cosigned the young artist’s pivot, saying it takes experience to get to a point where you outgrow the excessive violence in your music.

“It takes for us to feel before we actually learn,” he said.

“When you've been through certain things, it’s hard to feel good about putting out content that you know is poison.”

Healing & Hip Hop

As Dr. Sharpe mentioned, if we listen, the community tells us what it needs. The art that comes out of these communities, whatever brand of Hip-Hop, clearly outlines the needs in the music.

The need to feel seen, confident, powerful, resourced, and wanted is evident and worthy of exploration.

Hip-Hop, like Black people, is not a monolith. Hip-Hop and its culture is infectious, for good or for ill. As an art form from the streets, it’s a living breathing thing with potential that people from the margins of society can take pride in.

In the best of cases, Hip-Hop highlights the resilience, confidence, wisdom, and strength of marginalized people. It laughs, cries, and crip walks in the face of oppression. It has the power to encourage, inform, inspire and soothe souls. For those who face daily hardships associated with poverty and a structurally violent system that starts causing its harm from in utero, sometimes the pen, a rhythm and some bass is the only way through.

As for the more violent forms of Hip-Hop, Dr. Sharpe sees an expression of pain that we need to spend time unpacking.

“It’s not about “What’s wrong with you? Why are you rapping that way?” But “What happened to you?” “Is it steeped in trauma after trauma, of witnessing friend after friend being murdered?” That’s a very different approach, and where I think we need to be,” she said.

She and many other leaders believe that if we can genuinely come to understand the roots of these lyrics, only then can we begin to develop effective programs and interventions that create pathways for individuals to keep themselves and others safe.

By

By