He had been living in his car after losing his job and had slept there the night before. A civilian called the police, reporting a man talking to himself with an unleashed dog and "swinging a knife around." The knife, Fowlin later said, was one he used for cooking and prayer.

When police arrived, the knife was still sheathed in Fowlin’s waistband. Officers shouted commands and fired a Taser that failed to subdue him. As he backed away, asking them to stop, Fowlin pulled out the knife and raised it, not at the officers, but to his own neck. Minutes later, Constable Andrew Davis shot him twice, leaving Fowlin with permanent injuries.

The body-camera footage shows what’s now familiar in Toronto: a man in distress, a confrontation escalating too quickly, and no mental health professional present. What the footage doesn’t show is the alternative the city already has, which it is now quietly dismantling.

What MCIT brings to a crisis

For twenty-five years, Toronto's Mobile Crisis Intervention Team (MCIT)—a partnership between participating hospitals and the Toronto Police Service (TPS)—paired psychiatric nurses with specially trained officers to respond to 911 emergency and police dispatch calls involving individuals experiencing a mental health crisis.

These clinicians specialize in de-escalation, suicide intervention, and psychiatric emergencies. They respond to psychotic breaks, suicide attempts, children in crisis—and yes, calls involving knives.

One nurse, who asked not to be named, recalled sitting across from a young woman known to carry blades. She talked with her until the woman felt calm enough to drop the knife. No shouting. No weapons drawn. No injuries.

That kind of trust-based intervention is exactly what wasn't available to Fowlin.

“From what I read, it didn't seem like a 'person in crisis' call,” the nurse says. “But someone holding a knife to their own neck? We go to those calls all the time.”

MCIT's work often goes unnoticed because its successes are quiet. A conversation on a sidewalk. An hour spent in a living room. A voluntary hospital transport instead of a police takedown. The absence of drama is the point.

They typically have access to psychiatric histories, medication lists, and past hospitalizations before arriving—context police alone don’t have. It shapes their approach long before they open the car door. Their goal is simple: prevent a crisis from becoming a use-of-force event.

Psychotherapist Alethia Cadore, who worked in psychiatric emergency services when MCIT was first created, says the program broke patterns of fear and harm.

“The nurses brought empathy,” she explains. “People in mental health crisis, especially Black men, have been harmed so many times. MCIT interrupted that pattern.”

The program had limitations—restricted hours, too few teams, and no overnight service—but these were solvable problems. Expansion was possible. Improvement was possible.

The quiet announcement

But then came the announcement that changed everything. In October, MCIT officers received a memo saying the program would end by 2026. The nurses, who form half the partnership, weren't invited to the meeting.

“We had no idea anything was changing,” the nurse recalls. “Our police partners got the memo about a meeting at Toronto Police College, and we weren’t invited. We ride in the same cars every day, yet while they were inside, most of us were sitting out in the parking lot.” The timing was planned to coincide with shift changes. “That’s how we found out MCIT would be shut down. Second-hand. In a parking lot.”

Police Chief Myron Demkiw later softened the language, saying there’s “no timeline” and the program is being “re-envisioned.” But the direction remains: MCIT is being phased out.

Why TCCS won't fill the void

Police say non-violent mental health calls will be redirected to the Toronto Community Crisis Service (TCCS), a civilian-led program built to respond without police. TCCS is well-regarded. But it was never designed to handle the types of calls MCIT specializes in.

“TCCS is a fantastic program,” the nurse says. “But they're non-violent calls, and they're not acute calls. Anybody who's acutely suicidal, anybody with any type of weapon or aggression, or maybe even acutely intoxicated, and there's aggression, they're not going to go to. And they don't go to anybody under 16.”

MCIT responds to those calls every week: the teens on bridges, the people with knives who aren't threatening anyone, the children in crisis. They're the calls most likely to escalate toward injury or fatal outcomes when handled solely by police.

The nurse explains another critical difference: TCCS is consent-based. “The family can consent initially, but if they show up and the person's like 'I don't want to talk to you,' TCCS cannot continue that engagement.” For people experiencing psychosis or mania without insight into their condition, this becomes a barrier to care. TCCS also doesn't have access to medical records, the psychiatric histories and medication lists that help MCIT nurses shape their approach before they arrive.

Removing MCIT would leave a gap between what TCCS can do and what frontline officers are trained for. That gap is exactly where shootings happen.

The stakes keep rising

Toronto is making this shift at a time when crises are increasing, not stabilizing.

In 2023, 300 people experiencing homelessness died in Toronto, more than half from drug toxicity. Many were known to crisis teams. Others had cycled through emergency rooms repeatedly. The need for a coordinated mental health response has never been higher.

Yet Toronto approved its largest police budget in history—$1.22 billion, while mental health and housing supports lag behind. The city is choosing more enforcement; at the same time, it is dismantling one of the only programs designed to prevent violence during mental health emergencies.

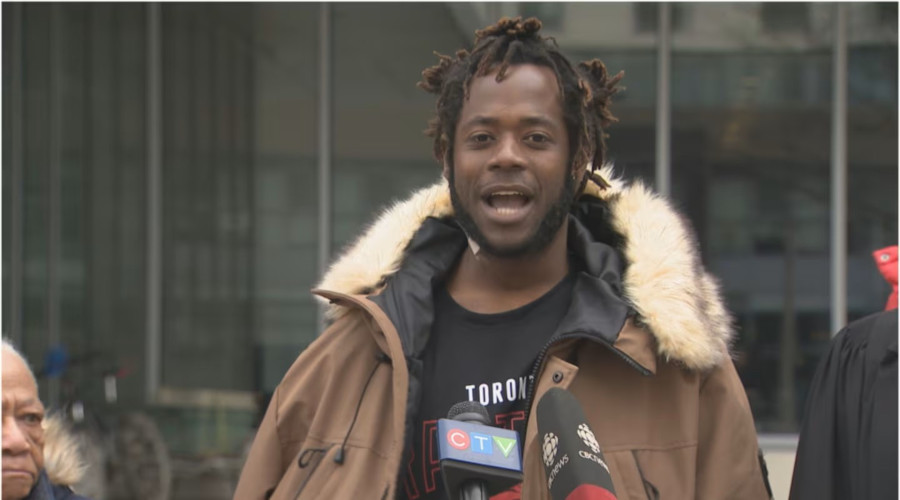

What Devon lost

Since the shooting, Fowlin has been living with permanent damage to his right arm. Recovery has been slow and difficult. A verified GoFundMe started by activist and journalist Desmond Cole has raised modest support, most of which goes toward basic needs. “Every dollar goes to essentials: food, winter gear, vet bills for his dog,” Cole says. “Devon needed housing and mental health support, but the state met him with bullets instead.”

Perhaps most striking is Fowlin’s response. “He's never been vindictive,” says David Shellnut, Fowlin's lawyer—also known as The Biking Lawyer. “Even after nearly dying, he didn't want to ruin the officer's life or family. That compassion, if only it had been mutual that morning.”

What happens when MCIT disappears

Constable Davis has pleaded guilty to reduced charges. Last month, he received a suspended sentence with one year of probation for assault causing bodily harm and a conditional discharge with one year of probation for careless use of a firearm. He will not serve time in jail. The sentence means he can keep his job as a police officer, though he still faces a Toronto Police Service disciplinary hearing and will have a criminal record.

But the consequences of eliminating MCIT will be far-reaching.

Without clinically trained responders, more calls will fall solely to the police. More people in distress will encounter officers without the tools or time to de-escalate. More misread situations will turn into confrontations.

“What happens to the high-risk calls?” the nurse asks.

Right now, there are no clear answers, and no replacement model that covers the scope of MCIT's work.

But the stakes are clear: when a city removes its ability to respond to a crisis with care, it increases the likelihood a crisis will be met with force.

By

By