Aside from the alphabet, they must have also learned the minimal value or expectation of success placed on them by society.

These inferior conditions were legally enforced through a “Common Schools Act” passed to allow for a separation of schools along religious lines; which also had the dubious effect of allowing for separation along racial lines too. These classifications included Protestant, Roman Catholic, or Coloured. This means the system literally reconfigured Blackness into a religion in order to support a racist education policy. Black parents and educators rallied against the injustice of their children’s predicament, and eventually succeeded in integrating the school system despite the excuses as to why this was supposed to be impossible. The last segregated school in the province of Ontario was shuttered. This was 1965.

Listen to the audio version of this article:

Fast forward 17 years. I am in third grade. It is the first time I was disciplined by a teacher for “talking back”. I honestly can’t even tell you what the subject matter was, or why it made her so angry, but she dragged me to the front of the class, bent me over her knee, and spanked me. This was a Catholic school in the 80’s.

I was, until I arrived in this teacher’s classroom, a pretty decent student. However, my initial report card did not reflect that. It was difficult to understand because I was doing my work in class. Both my parents asked for a meeting with this teacher, and apparently I was being graded negatively for my lack of participation in class. The irony of being spanked for participating in a class discussion, then being graded negatively for no longer wishing to participate in class discussion, is a textbook metaphor for the Black experience with White authority in the Western world. Perform like I want when I want or face the consequences. Accept you have no right to equality or there will be consequences. Demand justice and equality but do it peacefully. Demand justice and equality peacefully but don’t disturb my parade or my ride into work. This was now knowledge I had at 8 years old. Still, I managed to get to grade 4 on schedule despite this teacher. This was 1982.

I am 15 years old. I am a Grade 10 student at a Catholic high school maybe one city block away from my elementary school. I have never been what you could call gifted in mathematics and it drove my mother crazy. When I was in elementary school, she was the mom that tried her best to homeschool me after school. She would purchase educational activity books and I would do these exercises that she would mark when I was done. Grammar and math were her forte, and she was not having it any other way for her son.

I struggled through Grade 10 advanced math with a teacher who boasted of being open to tutoring after school, but whose tutoring consisted of doing the work for you, then asking “why don’t you understand?” I still went to these “tutoring” sessions after school until eventually this teacher said to me, in as defeated a tone as he could muster, “Promise me you’ll never take another math course again, and I’ll make sure you get a passing grade.” He said this with all seriousness. I of course, because I was 15 and ignorant (and wanting to go to university), thought this was a good deal. I passed Grade 10 math with a D grade that still haunts me to this day. More than that though, did this teacher ever think about what future career choices he had potentially eliminated for me? Finance, medicine, engineering, were all out of the question. This means he never really looked at me as someone worth the effort. I wasn’t worthy of being given the best chance to be something I wasn’t even thinking about as a young and unaware teen. Nope. In that moment, he had already decided for me that I was not going to possibly be any of those things, and I was an irritant keeping him from being able to take credit for the success of the kids who didn’t really need his help to begin with. This was 1989.

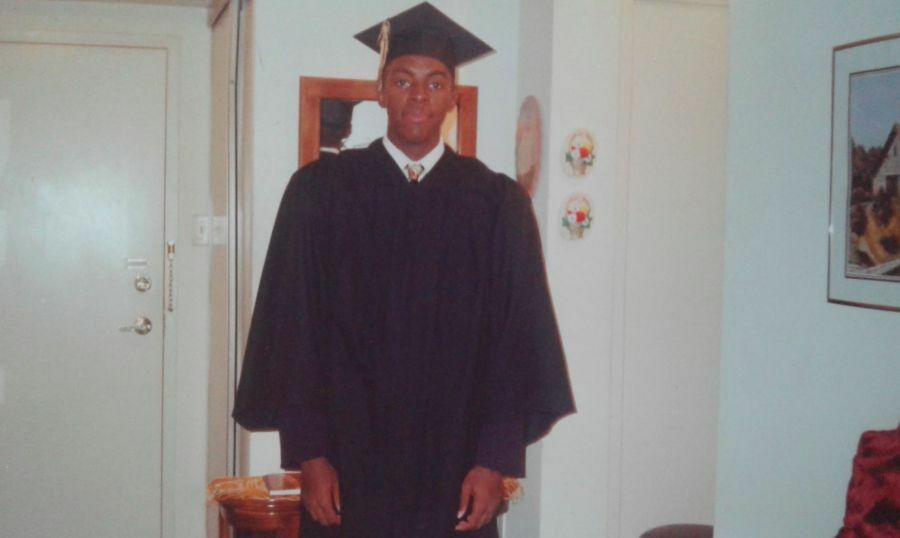

I am 17 years old. I’m in one of the easiest classes I’ve ever had in my life. I believe it’s a world history course of some sort. The teacher is also the coach of the basketball team. I’m friends with many of the guys on the team though. Entirely off stereotype, I cannot sink a basket to save my life. This teacher knows my relationship to most of the guys on the team, and upon noticing me in his classroom, approaches me at the end of class. He leans in close, places a paternal hand on my shoulder and says “as long as you try, I will pass you.” I think to myself, “isn’t that the point?” He continues to remark “Not everybody is book smart, but I respect the guys that try.” He said it so tenderly that I almost wasn’t entirely offended. Did this Caucasian coach of a basketball team of majority Black boys just basically insinuate that I wasn’t “book smart” for no other reason than I was Black, and hung out with the basketball team? I have to presume he believed I wasn’t too bright, and he didn’t think much of the IQ of the kids he coached either. I was offended on behalf of them because I know these guys actually loved this man, and thought of him as someone who really cared. I didn’t have the heart to ever tell any of them this story. As a grown man, I kind of regret I didn’t. I don’t think I did them any favours by allowing them to think this guy who respected their athleticism instead of their minds was an ally to them. During the Rob Ford era, whenever he spoke of his love of coaching his football kids, I always found myself thinking back to this moment. These sorts of people “love you” like benevolent slave masters who refrained from beating their slaves. That is to say, you’re still perceived as less capable, and the paternalistic/maternalistic treatment isn’t based on actual love, but rather, mercy. Instead of patronizing, which is actually what this is, they believe themselves to be benevolent. Still, I kept my mouth shut, nodded, and left the class. I made sure I passed that class with an “A” (an easy one at that) just to show this troglodyte Black people can do more than shoot a ball through a hoop. This was 1991.

I am 42 years old. Charline Grant is a mother of 3 children in the York region school system. She is only one among several concerned parents of Black and Muslim students who have filed a joint human rights complaint against the York Region District School Board. One of the complaints included the beating of a Black child by a group of White children as racial epithets were hurled at them. The assault was shared on social media, and initially resulted in no suspension for any of the White students involved. If they had killed this child, we would have been in our rights to call it a lynching. When you read this, keep in mind for the last five years Black student suspensions across the province have made up half of the suspensions in Ontario. There is clearly a different regard for Black student infractions than White students. Had a group of Black students beat up a White student in the same manner, would the penalty even stopped at just suspension? Would these Black students not be dissected in the media and described as thugs, savages or vermin in Toronto SUN op-ed pieces? This is only a small part of why Charline Grant was at this school board meeting to discuss equity matters with people implementing policy. This Black mother, like my Black mother, who came to the school to demand fairness and inclusion for her child, was making the same stand my mother had to make for me 34 years before. It is the same stand a group of Black parents had to make for their children 17 years before that. It is November 22, 2016.

This same system forced Charline Grant to endure the indignity of waiting for an internal investigation into a school board trustee overheard calling her a “nigger”, while ironically at a school board meeting discussing issues of racial discrimination with an adversarial board. It is the same system that allows the offending school board member the dignity of retiring rather than terminating her on the spot. It offers you half hearted assistance and steers you into a life of uncertainty or potential oblivion in 1989. It’s patronizing in its lowered academic expectations of you, while supportive and marvelling in your athletic ability in 1991. It makes inquisitive 8 year olds insolent and worthy of public humiliation through an act of violence in 1982. It is segregated schools, toilets overflowing with excrement, cramped classes with poor lighting, and the absence of equity without shame in 1965. In philosophy, it is now. Black students are still suffering. Black parents are still standing.

We have integrated the buildings, but does the separation still remain?

Byron Armstrong is a freelance writer and lifelong Torontonian, raised in Jane-Finch and living downtown.

By

By