I thought our identity was clear to my daughter. After all, our diverse family history is proudly recalled in the book, The Road That Led To Somewhere written by one of my maternal relatives. Our family traditions are a beautiful mosaic of many tribes both African and Indigenous. We are Ojibwe. We married into the Lubmee Tribe. We are card-carrying members of the Painted Feather Woodland Métis Tribe. One of the only tribes to recognize the Afro-Indigenous.

But on this day, my daughter was asking me a deeper question, one that the facts above would not satisfy. She was asking me to teach her how to respond to the scrutiny she innately knew would result from her application to an Indigenous Internship.

I was shaken because this explanation would require a departure from my well-articulated Canadian Black history lesson. I would have to delve into parts of my ancestry that are not as well known or understood. The specifics of which would cause me to take a closer look at my family ties and ultimately come away understanding that our Indigenous history is, in fact, more vast and interconnected than we realized.

This was hard work and a part of me was angry that once again I had to validate our existence to avoid invisibility and escape exclusion.

Let me explain what brought us to this conversation. My daughter had just graduated at the top of her class from the University of British Columbia with a Master’s degree in Water and Land Systems. She was job hunting and finally “adulting.” Anyone who has looked for work after a long educational career knows the difficulty of searching for employment and its weird required mix of self-promotion, exceptional confidence, and courage. But she was doing it and I was proud of her.

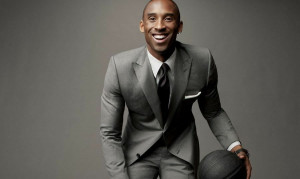

Nneka Allen & Destiny Allen-Green visiting the Grand Canyon in the fall of 2019.

Nneka Allen & Destiny Allen-Green visiting the Grand Canyon in the fall of 2019.

After weeks of applying with little response, Destiny mildly mentioned to me an Indigenous Internship position at a global company in her field. She wasn’t sure if she qualified to apply. This two-year position was an opportunity specifically for someone with Indigenous heritage. The answer was obvious to me, but my daughter was more than apprehensive. Over the next several days I found me and my daughter in a deep analysis of our identity, culture, and community. The reality of those conversations was a painful reflection of hidden histories and cultural erasure.

The unique stories of the Afro-indigenous are largely hidden in Canadiana. And in these moments Destiny felt like a fraud, despite her legitimacy. She was worried that her prospective employer would not accept her Métis status because of her apparent Blackness. And like any emerging adult, she was developing her identity. The reality was Destiny would have to quickly develop her cultural narrative and place it upon her head like a crown to legitimize her qualification for this role. She would have to find comfort in her story because she would surely need to share it many times in her life. For my introverted, peace-making science major, this reality was challenging. This would be Destiny’s first time explaining her ethnic uniqueness. And identity was the key qualifier for this employment opportunity.

My Crown - Forty Years in the Making

My family has been in Canada for over 170 years and in North America for over 450 years. Despite this truth, I felt like I had to defend our Indigenous identity because I felt unprepared and flat-footed to respond to my daughter's query.

As a result, I began to inspect how I was identifying myself both personally and professionally. I knew that my ethnic-cultural mix was common where I was from, Essex County in Ontario. But my daughter was on the other side of the country in a different province trying to explain histories omitted from the “Canadian Story.”

When visiting Toronto, the largest and most diverse city in Canada, my Blackness goes broadly unrecognized and almost always requires a detailed explanation. It was clear Destiny’s struggle would also include a rare history lesson. A lesson that would require confidence in our ancestral griots and our identity.

I am a descendant of the Underground Railroad. My family is made up of former slaves, free Blacks, and various tribes from First Nations, German, Irish and English settlers.

I am a Black Métis sixth generation Canadian Mother. It took me over forty years to fully articulate my identity.

My maternal ancestors, John and Jane Freeman Walls, escaped American slavery and found freedom in Canada in 1846 on the shores of Amherstburg Ontario. They were an interracial couple, African and Irish with a unique love story. In 1881, John and Jane’s son, James Henry married Parthena, the grand-daughter of an Ojibwe man, Thomas White Cloud Hopkins. Their granddaughter was my beloved great-grandmother, Myrtle Lucretia Walls.

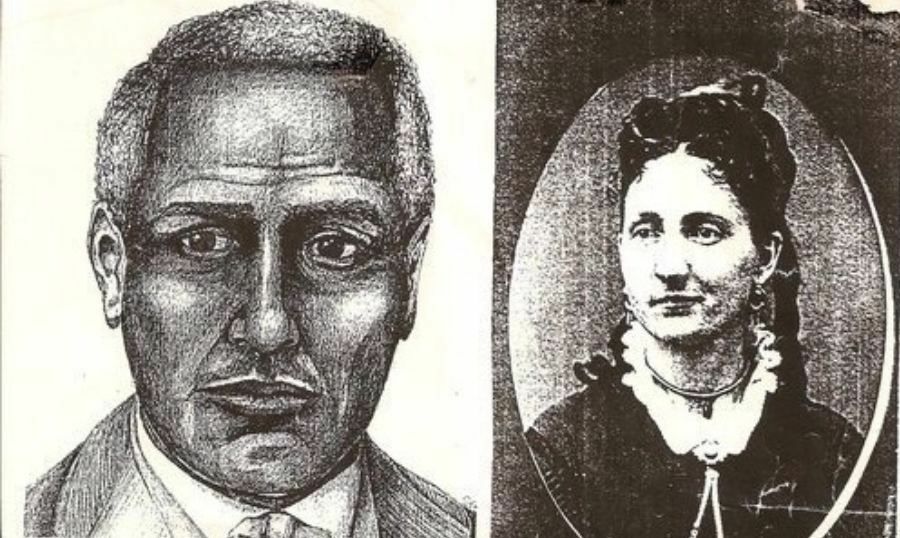

James Henry Taylor & Myrtle Lucretia Walls Taylor, my maternal great grandparents.

John Freeman Walls & Jane King Walls, 3rd great grandparents who escaped slavery in Troublesome Creek, North Carolina and arrived in Amherstburg, Ontario in 1846.

My paternal ancestors arrived in Canada around the time of the Civil War. Before and after arriving in Canada my ancestors married into First Nations communities. My second great-grandfather Benjamin Allen married Nancy Chavis descending from the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. In fact, two lines in my paternal ancestry married into the Chavis family prior to arriving in Canada.

In my pursuit of greater understanding, my ancestral research continues to produce new information about my identity despite the lack of slave records, documented oral histories and accurate racial/ethnic identification of free non-white persons. Every piece of new information is another brilliant stone in my identity, I wear proudly as a crown.

And she did it too! Destiny carefully created her identity crown, which has inspired curiosity and offered her success!

Destiny was the chosen candidate for the Indigenous Internship position. And she continues to develop her identity and narrative. This experience has given her the confidence to tell unheard stories in her unique voice. And I continue to watch her pay homage in subtle and powerful ways to our Indigenous roots. Like me, she too is clarifying her identity with every story told.

“Our crowns have been bought and paid for…All we have to do is put them on our heads.” ~ James Baldwin

By Nneka Allen

By Nneka Allen