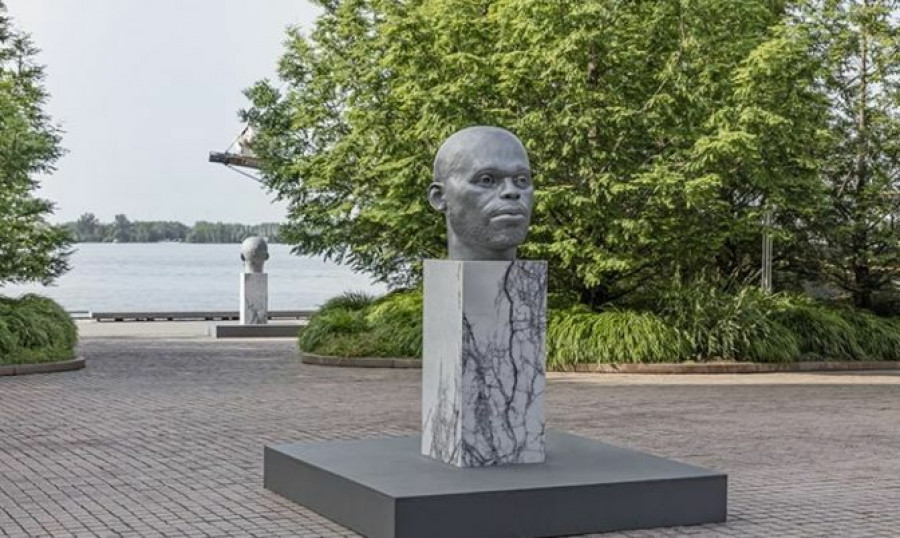

One artist has dedicated an entire installation to challenging these notions. I met up with UK based artist Thomas J. Price, who’s brought his stunning exhibit to Toronto’s Powerplant Contemporary Art Gallery. It’s called “Ordinary Men”, and it is challenging traditions with bronze sculptures of ordinary, fictional Black men in everyday poses. We strolled through the partly outdoor exhibit and chatted about Price’s inspiration and how these sculptures confront viewers.

ByBlacks: Bronze has traditionally been used throughout history as a material denoting wealth or prestige for a higher class. Would you say your usage of the material for these sculptures is either a critique, or reimagining of this tradition?

Thomas: It’s both. It’s about hierarchy of materials. Materials and scale in my work is incredibly important. Think back to the Roman days, when they would send an image of the Emperor around all parts of the empire to make sure that you knew that “this is power.” To me, these sculptures denote a sort of power on a smaller scale, that relate to this ancient Material (bronze) which is steeped in history and meaning. It’s attached to hierarchy which is attached to high status. It’s an expensive thing to work with, so there’s also a kind of prestige to the process. I’m using it to represent Black people who don’t even exist, in order to challenge the idea of who we see as having intrinsic value. When I speak of intrinsic value, I mean as human beings and as members of society. I reject the classical idea of what is great, and I’m placing myself and people who look like me at the centre. I don’t want to be “as good” as something. I want to be me. So it’s a different way of going about it, but a similar way of trying to empower an overlooked section of society.

ByBlacks: With regards to “Cover Up (The Reveal)” the figure appears to be wearing a hoodie just prior to “the reveal.” I wonder if what is being covered and revealed by the monument could also be conferred on to the viewer in terms of what their perception of the figure reveals about themselves? Prejudices, misconceptions, etc?

Thomas: Scale is one of the first things you’ll notice about this. It’s very important that this sort of mindfuck scale acts as an in-between so that it’s monumental, but still relatable. It’s not so big as to come off as architectural. I mean like, you can’t just dismiss it. You have a human relationship to it. This is still a person or a proposition about a person. The first question everyone asks is, “who is this? Who is that man?” When I tell them it’s a made up person, no one believes me initially. “Well, why is it there?” They just cannot make that jump between - “what has warranted the erecting of this sculpture? Why do they deserve that?” It’s a demonstration of just how a sculpture of a person is still seen as an indication of stature. So the idea is to challenge this whole idea of portraiture or statuary as being something earned, particularly when it comes to groups who aren’t white, by placing these fictional characters in those traditional modes. You don’t have to earn any respect to have a sculpture made of you.

ByBlacks: What’s the story behind the name for the sculpture “the cover up the reveal”?

Thomas: This work is definitely looking at racially based elements of state violence. The hoodie is this emblem which is being used to justify violence against Black Men. There’s no evidence to back it up, but it’s something that the media can use as a shorthand for “someone looks suspicious.” However, I know as a man that grew up wearing hoodies, you do it because it’s cold, or to hide yourself from judging gazes based on those suspicions. It’s a way of hiding your fragility away; especially if you’re a black guy and supposed to be hyper masculine and this kind of crap. What if you’re having a bad hair day? If you’re black though, that’s so loaded. So it’s called the “Cover up/the reveal” because it’s the ambiguity of “is he putting the hood up or taking it down? Is he just adjusting his collar?” It’s all about that in between action. The expression is caught in an in between, so you can’t say “oh this person is this or they’re thinking that.” What do you read into it? It’s about creating that extra narrative around it. I love placing these huge figures out in the public realm because you don’t know what you’re going to get in terms of interactions or opinion. Everyone can walk past. They’re not paying to go to a gallery. You get real feedback, but also in terms of the concept of this work, it’s about taking up space and getting people almost desensitized to an image.

ByBlacks: So people’s perceptions of black masculinity are what’s going to dictate how they see the statues?

Thomas: Exactly. It’s really in a way quite challenging. I think they’re quiet in the way that they do it. They’re very much allowing the viewer to open themselves up and just discover the things that are going on inside themselves, as opposed to saying “this is what’s happening” and closing it down. The sculpture’s effect is to make the viewer question what they think and why. I grew up very aware of how I dressed. How I stood. Was I smiling? It’s always a performance. That’s why my figures don’t smile. They’re not trying to look you in the eye. You, the viewers, do not make them exist. They’re there whether you’re there or not. And they’re not looking for approval or validation.

ByBlacks: The name of your “Numen” series relates to the Latin term for divinity or divine presence, and they’ve been placed in a classical Greco-Roman and Egyptian bust style. What are you trying to say about divinity or divine presence with the busts?

Thomas: Really, I’m not talking about the divine in terms of a real deity that is worshipped. I’m not talking about gods, Christians, or any other religion’s particular gods. I’m talking about the notion of what is worth worshipping, and subconsciously held beliefs about types of people. When you think of God who do you imagine? It’s probably going to be male, and quite likely, white. I always find it interesting that in African churches this white, patriarchal figure of “the father” continues to dominate. The more blonde, the more believable. It’s incredible. I think that just shows a huge element of social programming.

It’s at this moment as if on queue, a pair of young, black women begin posing excitedly with one of the Numen heads.

Thomas: I mean, look! You see. They’re seeing themselves represented like that. As soon as I installed these pieces in London, I had a black family come up and they couldn’t believe (sic)”What is this?” They just had this immediate intimate relationship of seeing themselves or seeing something they could relate to. It’s the second time I’ve displayed one of these, and I still get goose bumps now because it’s an incredible, genuine reaction. That’s just people reacting to an image that they haven’t seen.

ByBlacks: So is the idea of being just an artist, versus being a black artist, pretty much an impossibility?

Thomas: It’s a luxury that a lot of people don’t understand they even have. I think for me, as soon as I represented people who weren’t white, I was immediately asked “why do you only sculpt black people?” Which is a silly question to ask. The fact that I thought I needed to answer that question also gives me pause for thought. How have I been inducted into this? How have I been conditioned y’know? What things am I accepting that I should be reassessing, looking at, and trying to examine? Where does this come from? So I’m not really wasting my energy on trying to wrestle myself away from this label of black artist. I personally don’t use it. My work has been about what it means to have the experience of being black — I’m mixed race. My mother is white and my father is black; which perhaps gives me another perspective as well. It’s certainly part of my experience as a human being and is going to be a part of material as an artist.

I think it’s a very needed discussion that people need to engage with. I’m trying to convince myself that it doesn’t matter that people keep calling me a “black artist”, but it is an indicator of society’s need to pigeonhole or categorize. How does that limit the avenues that artists (wherever they’re from) have for acceptance as artists first. Women. Black and Indigenous people of colour. In terms of non-white (or non-gender conforming), it gets very specific in terms of what you’re allowed to do. I think it shows that there’s still a huge issue, and I think people who don’t have to experience that don’t want to talk about it. Their view is they aren’t racist or sexist, but they just want to live in a world where they can still benefit from all the things that are racist, sexist, discriminatory, or based in privilege.

ByBlacks: The privilege that supposedly doesn’t exist?

Thomas: Yeah, exactly right. What I’m saying is, you can’t have it both ways. You can’t say, “I’m not a racist but I want to maintain racist systems.” You’re not allowed to do that around me. You have to choose, because I’m too tired nowadays to even mess about with that. You see more of this populist facsism kind of wave sweeping through nations, trying to wash away the small change that we’ve made. I think that the trick is not to despair, but to double down and keep making stuff that addresses what’s happening in ways that people hopefully want to engage with. I think that’s why the arts have a place; because people are willing to step into that world to take time beyond their own struggles to engage with issues. You as an artist have this moment, and it might just be a fleeting moment, where you have someone’s attention. Someone who might want to be drawn into a thought process beyond, “how do I pay this month's phone bill?”

You can get that little moment, and then they can take on some of these ideas.

The Ordinary Men exhibit is on at Toronto’s Powerplant Contemporary Art Gallery until September 2nd 2019.

Byron Armstrong writes political opinion and in depth profiles of creatives and professionals within the spheres of art, design and travel. Follow him on Twitter: @Thebyproduct

By Byron Armstrong

By Byron Armstrong