A close cousin to February Black history month promotions, rainbow capitalism comes off as a disingenuine attempt to capitalize on the existence of others not represented equally on a year-round basis. Count the rainbow flags, shirts, beach bags, and ice cream products this time of year, and you’ll know exactly what I mean.

So, here we are in Pride month and, of course, I’m writing about Black queer and trans artists. Hypocritical? Maybe. As a writer, acknowledging this means making an honest commitment to recognizing people from within this community on a more regular basis. As a community, I think our collective commitment should be to recognize their right to exist once Pride month is over, and everyone puts their rainbow flags away. One way to do that is to educate yourself about the lived experiences of black queer and trans people, and I think artists are oftentimes the most impactful at communicating that level of human experience. Not just because they can effectively articulate the injustices they face, with or without words, but because they can also show how they resist those injustices through celebrating their loving relationships with each other and themselves. Here are two recent examples of Black queer and trans Canadian artists powerfully articulating their experiences through sound, narrative, and both moving and still images.

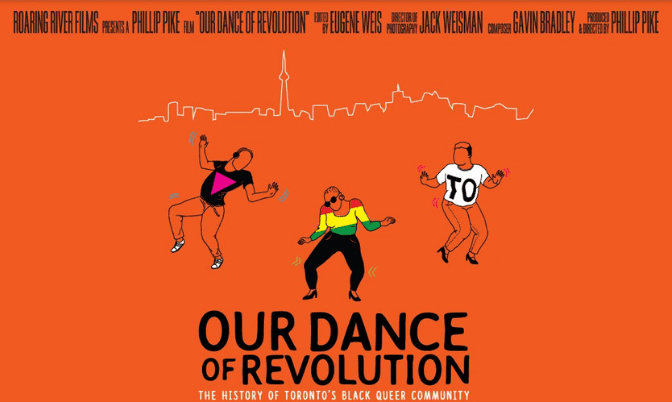

Our Dance of Revolution

The documentary film Our Dance of Revolution directed by Phillip Pike for Roaring River Films, tells the story of Black queer and trans activism in Toronto from the perspectives of those at the forefront of the movement. It takes us from the 80s Dewson House Collective at 101 Dewson Street, a commune of sorts for Black and Indigenous People of Colour (BIPOC) queer and trans youth in the 80’s, right up to Black Lives Matter’s disruption of the Pride parade and the present. There’s nothing like having a story told by the people who actually lived through it, and the authenticity and spirit of the movement explode off the screen as a result. The expansive documentary narrates a thirty-five year period that monumentalizes key organizations and individuals that came out of the Black Queer community through collectives like ZAMI and the Black Women’s Collective amongst too many others to mention. Thankfully, the “dance” doesn’t just focus on pain and struggle like some document of never-ending trauma. Instead, this is also a story of found family and generations of friendship and self-love that ultimately provide the emotional support to do the work of resistance. The film was well received at its official premiere at the 2019 Hot Docs Film Festival and continues to be screened around the world, currently holding a spot at the Mumbai International Queer Film Festival.

Variations in Black, Queer, and Otherwise: Works by Abdi Osman

Currently on exhibit at the Art Museum of the University of Toronto, Somali-Canadian artist Abdi Osman challenges notions of what it is to be African, Black, Muslim, queer, and trans. For example, in the Discovery Series (2007), Osman poses as himself in casual contemporary clothing, in drag as a veiled Muslim woman, and in traditional Somali male attire. He takes the same approach in the Discover Us Series (2008 - 2009), where he documents black queer and trans Africans in similar poses. These photographic series cause you to question your beliefs about queerness in not just a Black context, but also geographically (African), and religiously (Muslim). The Passport Series (2017) uses Osman’s passport photo printed on several large-scale scores of linen, all lined in a row. As a Canadian citizen who immigrated here as a Muslim Somali refugee, walking around them one by one mimics Osman’s experience of passing checkpoints and border crossings. Supposedly representing his citizenship and his “belonging” to Canada, Osman’s passport is notably a ten-year visa that is affixed to a Canadian passport that enables but does not guarantee entry into the USA. It speaks to the heightened state of surveillance, particularly as it relates to Black and Muslim bodies travelling from one place to the other. As with Our Dance of Revolution, Osman does not use his work to dwell on dark subject matter or “trauma porn.” Through series like Labeeb (2012) and Plantation Futures (2015), he instead focuses on intimate portrayals of queer and trans friendship and family; what he calls “everyday love scenes.”

By

By