Stylizing his public images after runaway slave posters from the 1800's, Wayne Dunkley has managed to create little monuments to Blackness in a public space, while asking the public for honest first reactions to those monuments. I had the chance to talk to Wayne about the danger of inviting public discourse, the gallery versus social media, and Black identity as an artist.

Can you talk a little about your goals for #WhatDoYouFeelWhen and what it’s all about?

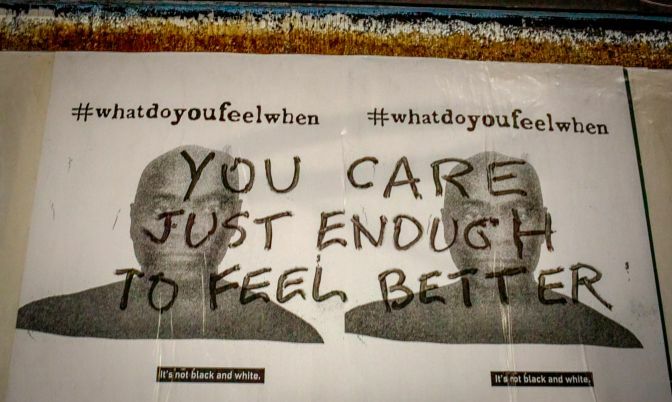

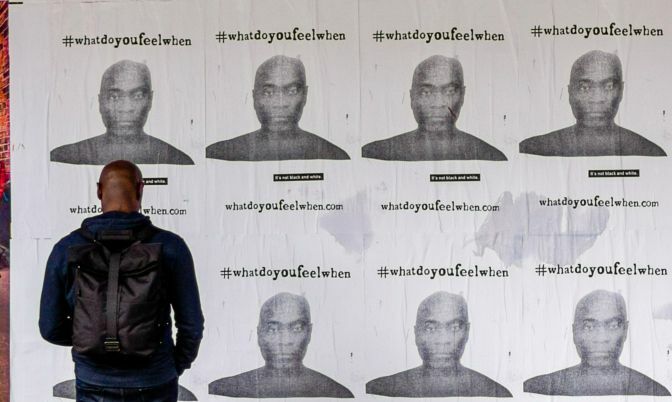

Launched at the end of September 2018 with the support of Canada Council for the Arts, #whatdoyoufeelwhen brought 1000 24x36” posters to Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto, and Montreal. I travelled to each city to document, photograph, and begin the process of building a different conversation on prejudice. Today, issues of prejudice (not only racism but many others as well) are front and centre in media and public discourse. The #whatdoyoufeelwhen project is designed to capitalize on the current growing awareness by placing a number of posters in several cities, while leveraging social media to help direct and stimulate the conversation. 1000 posters, 4 cities, and one face. The work intentionally provokes people to consider who, or what, is in front of them.

Is there power in both allowing others to speak without speaking, as well as allowing yourself to engage in, or direct the conversation?

By intentionally putting myself in front of another, I initiate a conversation with their internal dialogue. It’s what we naturally do when we encounter another person. By using an image of myself that looks a particular way, I am able to direct that conversation to engage a viewer’s personal story. This is a process that is rooted in history and has been going on for hundreds of years. The image on the #whatdoyoufeelwhen poster is stylized after escaped slave posters from the 1800s. These images were put out in public to hunt down and capture in pursuit of another person; I am putting these images out in pursuit of capturing something else entirely.

Your work invites the community at large to talk and take ownership of their feelings, which sometimes means hearing ignorant (though honest) reactions; which are feelings your work invites. Are you ever disturbed by any of the responses your work has garnered, and how do you deal with some of the most emotionally damaging commentary?

Reactions to the work vary greatly. Even though the work is designed to provoke, it is never intended to be accusatory. I tend to move past offence, and move into the realm of what is going on in that person that got them there? Yes, we react and need the space to be able to do so, but part of the problem is that most often we’re reacting to something within ourselves and projecting that reaction onto others. We all bring our experiences and our baggage to each conversation. Again, it’s that internal dialogue that I’m interested in.

As an artist, specifically with regards to #WhatDoYoufeelWhen, you are definitely taking yourself out of anything close to a “safe space” and putting yourself out there. You are literally putting your face on display and asking the random urban dweller for how that makes them feel. I’m curious about whether you think the idea of “safe spaces” is something that, as an artist engaging with the world, you should (or can) even care about while still being effective at making people think?

Creating a safe space isn’t a goal, it’s a by-product. The trick is to be able to make work in a sweet spot on the continuum between safe and threat that doesn’t allow for someone to simply react on auto-pilot. What I’m most interested in, and what’s at the core of this project, is that moment of encounter. What happens inside of us when we encounter someone different from ourselves? I recognize this moment of encounter can be a moment of discomfort and yet, discomfort can stir us to consider things in ways we could not or would not have before. I want the discomfort in my work to create a dissonance with the viewer’s world view, in turn opening them to question their unspoken assumptions. There are a 1000 things that happen in our minds subconsciously in a moment of encounter that we don’t even realize effect the way that we respond to the person in front of us. I am trying to expand that moment so that we can see the accumulation of all the other things that are going on. It’s like taking a portrait with the burst photo mode on your phone, the camera takes multiple photos at once - allowing you to look inside of a moment and realize there are many things going on that feed into the final photo; the tilt of your subject’s head, the movement of their eyes, the upturned corner of their mouth. All of these elements are constantly changing. The closer you look, the more you can begin to see all of the pieces and elements of the moment that combine to give you a whole picture of a person.

Politically speaking, much of the very right-wing nationalist rhetoric, though surprising for many, has been potentially attributed to certain elements in the community always holding these views (ie. anti-immigrant), but only now feeling emboldened enough to make them known. Do you think there’s a danger in not allowing for views contrary to your own in public discourse, or do you think those views incite more danger if allowed to be shared? Where does #WhatDoYoufeelWhen sit in either reasoning?

There’s a push to polarize. Public discourse is public for a reason, when contrarian views are suppressed, they will, inevitably, emerge in other less healthy ways. Of course, blatant hate and disrespect should never be tolerated, yet I feel as though some of what we see today comes from people not being given opportunity to voice difference. The challenge is to create contexts where those views meet others in respectful ways. We are often governed by our opinions on a handful of single issues that, when stitched together, are less a cohesive belief system and more a collection of the things that we fear, or things that challenge our assumptions and threaten our comfort and familiarity. There’s a push to categorize. We encounter someone and we want to put them in a box so that we know how to socially engage them. We do that instinctively. Sure, we can start with some of those categories, but are we limited by them? At some point we need to shift from identifying someone by the category we think they so neatly fit into, to identifying a fully realized human being with a name. At the end of the day you’re dealing with an individual who is living in front of you.

You’ve said your web-based art practice focuses on the challenge of creating spaces. How does the idea of creating space figure into #WhatDoYouFeelWhen on both a physical and intangible level?

The poster itself is claiming a physical space in the midst of the cacophony of noise out there. It takes its place alongside an endless stream of advertising and other things demanding our attention. It becomes a visual pause. As a photographer, I’ve always been interested in what’s going on beyond what we can see with our eyes. My first solo landscape show was entitled “Other Places”. This is in reference to the idea that the way we perceive an image is shaped by our history and experiences. This is similar to the moment of encounter and how we view those who are different from us. This concern of looking behind, looking below, and looking further inside to see what’s going on, has long been a part of my practice and is an essential element of #whatdoyoufeelwhen.

In the ongoing debate about whether street art is vandalism, there seems to be a very Black and White view. Either it is, or it isn’t. Obviously you don’t qualify your own work as vandalism, but do you think there are times “street art” actually does qualify as vandalism?

I reserve judgement on most street art except for when it infringes on pre-existing public work. I think public spaces have been primarily co-opted by advertising which I find problematic. In a way we're saying the only avenue for legal visual public discourse is through advertising, and that’s extremely limiting.

Once you’ve completed posting the 1000 flyers across 4 cities, do you have any plans to go back, collect some of these, and do a proper gallery show with some of them in the future? Do you think that having these shown in a gallery somehow takes way from the impact of the work?

Absolutely not. As the project continues to grow and evolve, a gallery is just one of many possible ways to further engage the work. One of the things that distinguishes #whatdoyoufeelwhen from degradation and removal of the/a black male is the emphasis on the photographic image. Having travelled to each city, I have thousands of photographs of the posters in each location. One image is an entire story in and of itself. The richness of the photos makes this a natural fit for a traditional gallery context. Viewing an image of the poster creates yet another level of encounter.

You’re both a photographer and new media artist. Social media, specifically Instagram, is a form of new media that appears to have bypassed the gallery system and allowed for more artists to not just be seen, but also make a living. As someone who has shown work both in galleries and on the street, and also engages in the use of social media to show your work to the world, how do you see that changing the importance of galleries in the future…if at all?

I believe galleries will always have a place. There’s a specificity to a gallery that can’t be replaced by Instagram. I’ve been really fortunate to live through a period of history where technological discoveries are happening at an accelerated pace. We have an insatiability with the new - we’re constantly wanting to displace what came before. The result of that is we rush to replace the old with the new - should video replace film? should digital replace analogue? What tends to be the case is that room is found for both. We assume when a new form of technology appears that it will displace old forms, over time we come to realize the value of the two coexisting.

Are you a Black artist…or an artist that happens to be Black? What is the importance to you?

I am both and I am neither. If the association with blackness means that my work becomes limited in the scope of its reach and accessibility, then that’s a concern. If that association allows for someone to find a place in my work, then so be it. For me, it goes back to the simplest of elements...this is a story and this is who it’s from.

Byron Armstrong is a freelance writer and lifelong Torontonian, raised in Jane-Finch and living downtown.

By

By