The 20-year-old environmentalist and climate activist currently studies at Trent University and challenged herself to become the first Black woman to hike the entire trail.

Zwena and her walking partner hiked for 8-10 hours, travelling 15-36 kilometres daily. While researching, Zwena learned about the trail's connection to the Underground Railroad and decided she wanted to explore and share what she learned. She met with local leaders and historians along the way.

Her other goals for the expedition were to break down barriers, encourage BIPOC to enjoy the benefits of being in nature, and express her surroundings' beauty through art.

What led you to get into climate activism and study environmental science?

Throughout high school, I attended different semester-long programs where I travelled to a location and intensively learned about a specific topic. Two of those were environmental stewardship and activism. Those schools were where I sharpened my tools and expanded my knowledge about climate justice. However, I realized that Black people were being left out of the climate activism story once I attended. So, I wanted to share stories and provide a space for Black people to be engaged with the outdoors.

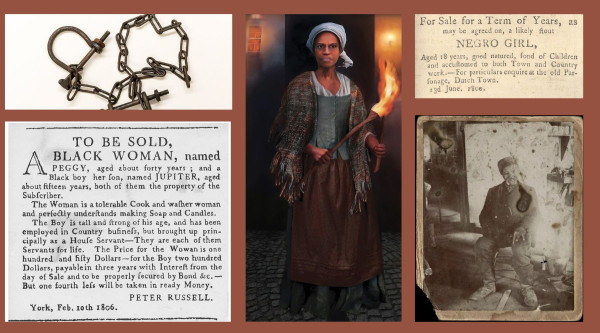

Can you tell me about Bruce's Trail's connection to The Underground Railroad?

While researching the logistics of the trail, I came across a snippet on a website about the trail's connection to the Underground Railroad. Those connections were in St. Catharine's and Owen Sound, where people used Underground Railroad terminals to seek freedom and create a new life. So I decided they'd be great places to connect with some historians and learn.

I stopped in St. Catharines and talked to a historian who told us about Harriet Tubman's connection there; that's where she'd take people coming from the south into Canada. So that was the first stop. There's also a point in Owen Sound, which was further north. People travelled there because there was a law that if you were enslaved, you could get taken back; crossing into Canada wasn't instant freedom. So people had to traverse further north.

The historians I talked to in St. Catharines and Owen Sound were descendants of people who came to Canada via the Underground Railroad. It was an impactful, powerful, and different type of storytelling. You usually visit a museum and get someone narrating somebody else's story. But this was a close, intimate history that feels different than when you're just learning about it from somebody who isn't connected. So I was grateful to have connected with both of those people.

How did people react to your plan to take on Bruce's Trail?

When I told my family, they said, "here she goes again." They weren't surprised at all, so that was kinda funny. Then when I began to expand to social media and reach out to people outside my circle, it was such an amazing connection. I met many other Black women leading outdoor organizations I wouldn't have met before. I was grateful for that. There was so much support, people giving gear, and financial aid, recommending people to stay with, and I was pleased with the feedback I got after releasing the project. There may have been some negative feedback, but as a positive person, I tend to focus on the people cheering me on.

{https://www.instagram.com/p/CeKF6dTJjtY/}

What are some of your takeaways from the trail from an environmental standpoint?

I appreciated that when we started hiking in April, there were almost no leaves on the trees, but everything was in full bloom by June. Being one with our natural environment gave me some perspective on the work I want to do within climate justice and activism. If you're not engaging with the environment, you're losing perspective because the environment has its own story. So, I considered it as learning, taking it all in and gaining perspective instead of coming into it with my own biases; I think that helped.

You've said one of your goals is to encourage Black and racialized people to "participate in nature." What exactly does that mean?

Participating in nature means tuning in on the trail, which is hard for a university student. For example, usually, while out on a hike, I'd be worried about what assignments I have, what's happening at work, and all these different things, but taking that much time out allowed me to sit and listen and be in the environment and always spend time figuring out other ways to care for the environment. So that's what participation in nature means for me; it's just being outside and taking that time to hike in silence, listening to the birds.

On the trail, we were given sage and tobacco from an Indigenous elder, and if we'd pull a wild edible to eat, we'd give sage and tobacco to the plant as a gift. So we picked up these tidbits of knowledge as we were hiking and finding different ways to show gratitude for the land we were walking on.

Why is that important to you?

It's important because BIPOC are on the front lines of the climate crisis. When you think about redlining and systemic racism, and climate racism, these all impact where Black people live. So, creating a space to have those conversations about how the climate crisis impacts the Black community was super important to me.

On the trail, one of my goals was to show Black joy. I showed viewers how to do their hair while on the trail. I wanted to highlight the fun and the freedom the trail brought. So much of my research was on people seeking freedom, so it was a continuation.

I also want to hold events where we discuss how to pack a backpack and explain the different terminologies because climate science has so much jargon. I want to be a middle person to translate that to community members.

What tips or changes can people make in their everyday lives to live more sustainably?

My first environmental love was composting and worms. I think it's a cool and easy way to get into it because it's just a food pile, then you turn that into the soil you can garden.

Using reusable water bottles is an easy thing to do. I started bringing reusable cutlery everywhere I went. I'm that eco-person that's gonna give you a bamboo toothbrush for Kwanzaa.

But being an environmentalist isn't about what you can buy; it's also about the conversations you're having because the climate and the environmental movement have been greenwashed and whitewashed. So, it's important to remember you can make a change by having conversations within your community about what the climate change crisis looks like. I remember my grandmother saying it wouldn't have been this hot 50 years ago; that's knowledge.

It doesn't cost anything to have conversations; it doesn't require a degree. Just being able to talk to your community and organize is super important. That'll continue to be important as the climate crisis progresses; things like community gardens and building community are the most effective ways.

What are some ways we can go about changing the way that we think and talk about the climate crisis?

It's essential to get information from different perspectives, whether you disagree or not, because it can help you expand your view of the issue. So, be open to changing your mind and opening your mind to grow.

I think that could help everybody in the climate crisis realize that we must look at this intersectionally. The climate crisis is a layered issue, not only of the environment but of race, of housing; all these different things are layered to create the climate crisis. So being open to different perspectives and looking at it from different sides is what I recommend.

By

By