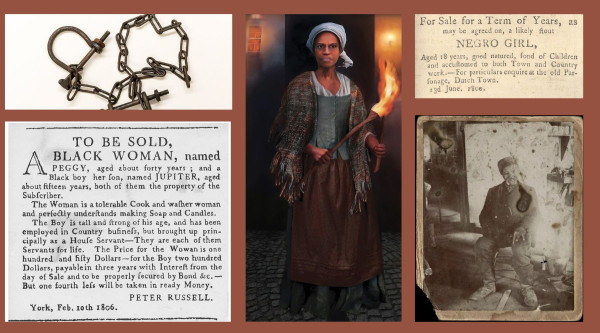

He had left behind the Jim Crow laws of the American south, which disenfranchised, segregated, and controlled the lives of African Americans, to embark on a journey that would take him first to England and then thousands of miles to the open unsettled prairies of Canada.

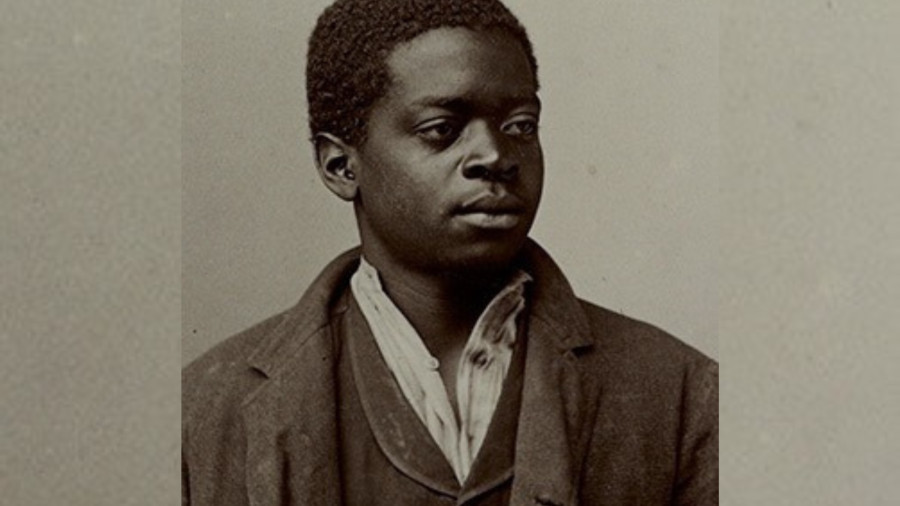

When Benjamin landed in Cardiff, he decided to make his way to London, a 150-mile trek he made on foot. Upon arrival, he was taken in by the Barnardo Home, a London-based charity created by Irish-born philanthropist Dr. Thomas Barnardo in 1866.

A year passed, during which time the staff at the children’s home tried to contact Benjamin’s relatives in America, but their letters went unanswered.

Over 60,000 boys like Benjamin were sent to Canada to "have a better life" - some were orphans, most were poor - and usually worked on farms until they came of age. Some became part of the families they were connected with, many were abused, others who were supposed to go to school could only attend according to the needs of the farmers.

So what was Benjamin's fate?

In March 1892 along with hundreds of other teen boys, Benjamin left England to join this Canadian farm training program. He would have been the only or one of very few Black boys in the group.

They sailed from Liverpool to Montreal, then continued by train westward to Barnardo’s 10,000-acre farm in Russell, Manitoba. Among the items Benjamin would have received as part of his “Barnardo Boys Canadian Outfit” were a pair of rubber-soled work boots, woollen socks, a boot brush, a New Testament bible, a traveller’s guide, and a copy of The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan.

The work day started with a bugle call at 5 am, a mid-day lunch, and ended at 6 pm. The house master and manager recited twice daily prayers, and there was a full church service on Sunday. Once the boys were trained, their one-year indentureship began on the various farms in desperate need of labourers. This is where Benjamin learned how to farm and care for livestock, among other tasks and chores.

According to research by Dr. Daryl White:

"By 1901, Washington was a domestic servant in Edmonton to prominent local resident John Norris. Norris was a former HBC employee who became an Edmonton rancher and was a partner in Norris and Carey, one of the first stores in the community. Washington earned $180 a year (for comparison, a men’s bicycle cost $35 from the Eaton’s catalogue) but his room and board would have been included. Washington relocated north with Norris to Athabasca Landing a few years later."

In the ensuing years, long after he had left the training farm to strike out on his own in Alberta, Benjamin worked with various families on their homesteads in exchange for room and board while his desire to have his own farm became stronger.

In April 1908, the first of many Black families fleeing the Jim Crow Laws and racial discrimination of Oklahoma started arriving in Alberta. Benjamin would undoubtedly have heard of the racial problems these newcomers were having and perhaps knew that his very survival meant he would have to distance himself from them. He had left his worries and trauma behind in America, as they had done, and never looked back. Instead, his focus was on acquiring land, and he started that process in August 1909. As part of the process, two other farmers had to vouch for Benjamin and his ability to break land, farm crops, and care for livestock.

The inevitable happened just a few years later when a resolution was passed by the Edmonton Board of Trade on April 18, 1911, requesting the Canadian government to restrict the settling of Black homesteaders in central Canada and to segregate those already living there to an area away from white settlers. But Benjamin never lived in any of the Black communities of Pine Creek, Keystone, Campsie, or Junkins. He managed to remain for for a number of years, in the all-white area of High Prairie with its Dutch, English and Norwegian settlers.

Benjamin seemed to be having a lot of success as a homesteader so it's not exactly clear why he decided to make a career shift during the First World War. But just before his 40th birthday, he travelled to Edmonton to enlist in the military. He passed the medical test but was turned away because he was Black, in spite of federal orders that people should not be refused based on race. Benjamin was told that he should go to Montreal where there was a segregated unit.

On September 16, 1916 Benjamin enlisted in the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force in the No. 2 Construction Battalion, the first and only all-Black battalion in Canada’s military history.

Other volunteers like Columbus Bowen of Paxson and Quesker West of Athabasca Landing, both 21 years old, travelled from the growing Black communities north of Edmonton into the city to enlist. Less than a year later, Benjamin and the other soldiers embarked on the S.S. Southland in Halifax, bound for England on March 28, 1917, and arrived in Liverpool on April 6. The men went on to France, where among many tasks, they supplied lumber for the front and water for their troops in harsh weather.

Major Cole Harston, a 43-year-old native of North Carolina in the all-Black Battalion, was a friend of Benjamin who chose to list him as his next of kin instead of his own brother. It is possible they could have met in the Edmonton recruiting office when they were enlisting. Harston lived in Edmonton with his Quebec-born wife, Rosanna. But it appears that Harston died of pneumonia before he could make it overseas. Benjamin stepped in to make sure Harston's wife was taken care of. Privates were paid $1.10 per day, and they could assign part of their salary to their wives or family back home. Benjamin never married, but instead sent $135 of his pay to his friend's widow Rosanna.

Benjamin returned to Canada in 1919 and several years after the war, applied for a Soldier Land Grant. He waited for two years until the Canadian government finally approved his ownership of 160 acres in 1924. He worked hard and lived a simple life, owning two granaries, a log barn, and several cattle and horses. Over eight years, he broke and cropped over 90 acres of land. Benjamin never had a fancy life, just a free one.

The bold teen who may not have felt he had anything to lose by boarding a cattle boat, who experienced hunger and homelessness, who crossed the Atlantic several times, who had served his adopted country in a foreign land, and who successfully fulfilled his dream of becoming a landowner, still in his later years could not even read or write and regularly signed his name with an “X.” He was known as a farmer, a soldier, and a gentleman.

Benjamin Washington died on February 28, 1966, in Oliver, Alberta.

This story is part of our "Black History Month" series, where we celebrate the remarkable journeys and accomplishments of Black Canadians.

By

By