But because a community showed up for a young girl who needed them most, and in return, she would grow up to make history for an entire nation.

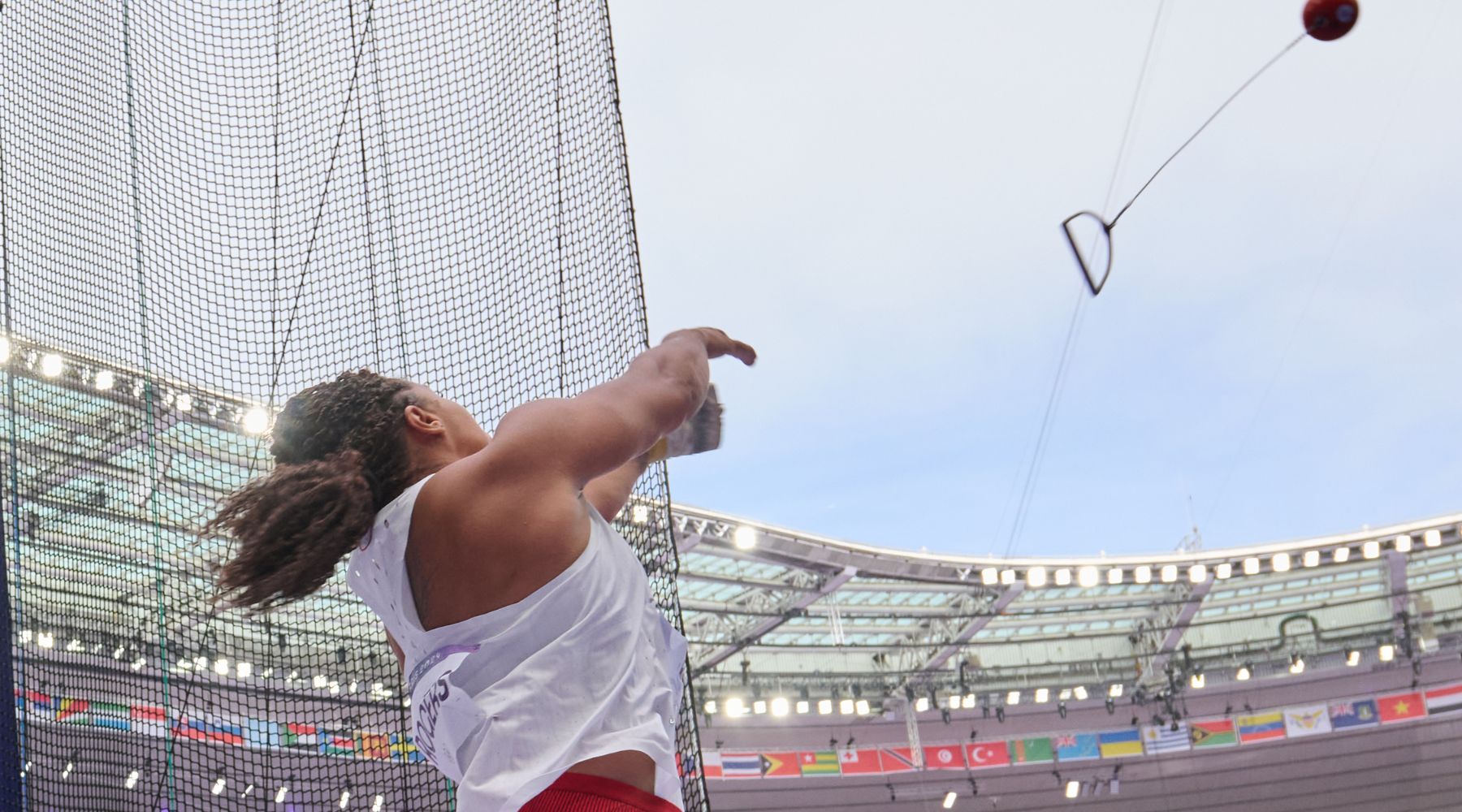

Today, Rogers stands as Canada's first-ever Olympic gold medalist in women's hammer throw and the first Canadian woman to win Olympic gold in any athletics event in 96 years. But her path to the podium? It started in the back seat of a car, couch surfing with her single mother, and learning what resilience really means before she ever learned to throw a hammer.

Before Rogers became a world champion, she was just a kid trying to survive. Her mother, Shari—a hairdresser fighting to keep them afloat—faced down impossible odds. Single parent. Mounting bills. A mortgage that became a millstone. When selling their home didn't bring relief, mother and daughter found themselves without a safety net.

"We spent a year couch surfing with friends, sleeping in our car," Rogers shares, her voice steady with the kind of strength that only comes from lived experience. "We slept at her work a couple of times because she worked with some aestheticians who had those beds [for treatments]."

But here's what poverty couldn't touch: Shari's determination to protect her daughter's dreams. She secured subsidized housing through an organization called More Than a Roof, where they would live for the next decade. That roof became the foundation for everything that came after.

It was a client of Shari's who first mentioned the local track club in Richmond, BC. No grand plan. No Olympic aspirations. Just a suggestion that maybe track could give Camryn something to focus on.

Those clients who happened to be part of the local track club showed up in a big way, taking Rogers to practice, bringing her home, making sure she was safe.

They told her to try running. Instead, on that very first day, a coach brought her to the throws area. She was a natural. What happened next would alter the trajectory of Canadian sports history.

"I got to meet all the throwers," she remembers. "Everyone was just so nice and so welcoming, and I felt very accepted into this group and into this community right away. It was the first time I'd ever experienced that as a kid, which means a lot to you when you're younger, and you're trying to find your place."

By 5 PM that day, 12-year-old Camryn Rogers was throwing a hammer. Within hours, she'd found not just a sport, but a family, and she's never looked back.

The seeds of Olympic glory were planted early. Roger had performed in a choir at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics' opening ceremonies while still in elementary school—an experience she cherishes to this day, still keeping the outfit she wore. But it was watching the London 2012 Summer Olympics, the same year she started track, that crystallized her vision.

"I remember watching the Olympics, watching our Canadians compete, and I was like, 'wow, this is so amazing. I hope I can be there too one day. I can't imagine how cool it would be to represent your country and to be performing on the world stage and make Canada so proud'."

By 2019, competing for the University of California, Berkeley, Rogers won her first NCAA championship in Texas, breaking the 70-meter barrier and qualifying for senior worlds. That's when the impossible suddenly felt inevitable.

"I just remember feeling like I had really taken a first big throw where I felt super powerful, and everything worked together," she shares. "Because the Olympics were going to be the following year I just thought to myself, 'I'm not super far off from the qualifying standard now. I think I could actually do this', which was quite surreal."

What sets Rogers apart from many elite athletes is her commitment to education alongside her athletics. While competing at Berkeley, she didn't just show up to throw—she earned three degrees. A double undergraduate in political economy and society and environment. Then a master's in the Cultural Studies of Sport and Education, where she tackled the systemic barriers international student-athletes face in profiting from their talents.

When Tokyo 2020 finally happened in 2021, amid a global pandemic, Rogers competed in empty stadiums with artificial crowd noise piped through speakers.

"I remember thinking, ‘this is so strange. I'm at the Olympics, and the stadium is empty. They had fans cheering on the speakers. It was wild," says Rogers.

She finished fifth, becoming the first Canadian woman even to reach an Olympic hammer throw final. But she was also finishing her master's degree. The youngest competitor in that final by almost two years was already thinking bigger.

Two years later in 2023, Rogers smashed the World Championships in Budapest. That victory made her only the second Canadian woman ever to win a World Athletics Championships gold medal, joining hurdler Perdita Felicien, who had accomplished the feat 20 years earlier in 2003.

Up until that point, Rogers had been competing without a major sponsor. But the Budapest victory sealed the deal with Nike, and she signed her name on the dotted line the very next day for a multi-year sponsorship.

{https://www.instagram.com/p/C7W2zF2OtO2/?hl=en}

Her swag was different in Paris 2024. Rogers arrived as the reigning world champion and the favourite to win—a pressure few athletes handle with grace. But pressure has been Rogers' training partner since childhood.

In the final, American Annette Echikunwoke took the lead in the third round. Rogers was in second heading into her final two attempts. Everything she'd worked for—13 years of dedication, countless hours of training, her mother's sacrifices, a community's belief- came down to one throw.

Her hammer flew 76.97 meters, almost 1.5 meters ahead of the silver medalist. History made. Dreams realized. A packed Stade de France erupted as Rogers became the first woman from the Americas to ever win Olympic gold in hammer throw.

{https://www.instagram.com/p/DPhDJvpDw2p/?hl=en}

This time, unlike Tokyo during the pandemic, her mother was there. Shari Rogers, who had sacrificed everything, who had shielded her daughter from the worst while nurturing her best, was front and centre for it all.

Shari clutched a necklace Camryn had given her when she was just seven years old, a necklace she wears to every single competition, holding it tightly each time her daughter throws while looking away, because she's too nervous to watch.

For Camryn, the real victory was being able to show her mom that everything she did to get them back on their feet was for these big moments. "Even on the days when I would have trouble seeing those bright sides, she always did. She always saw my potential and believed in me.” Rogers’ mom has travelled with her to every international medal she’s won, every championship, including the NCAAs.

{https://www.instagram.com/p/C7UrrQUvYAp/?hl=en&img_index=1}

Thanks to Rogers and fellow Canadian Ethan Katzberg, Canada has become a hammer-throwing powerhouse, with both sweeping gold medals at Paris 2024—only the second time in Olympic history a nation accomplished this feat. Together, they've put a once-obscure event on the national map.

What most people don't see, though, is the crash that comes after the high. Rogers openly shares her struggle with post-Olympic depression, a phenomenon common among elite athletes but rarely discussed.

"It's really hard to explain that feeling, and it's so overwhelming and overpowering. It's like this high, and then it can be followed by a really big low. I was going through it for a few months. It took a while to get out of it and feel very normal again."

Think about it: 13 years of your life dedicated to six minutes of competition. One minute per throw. The intensity of that singular focus, the achievement of the impossible, followed by the question every champion must face: Now what?

Rogers found her answer in movement, literally. Her coach relocated to Austin, Texas, so she followed, maintaining her training schedule while also job hunting. Her plan: work in the field informed by her three degrees until she retires from throwing, then attend law school.

In 2025, Rogers continued her dominance, setting a new Canadian record of 78.88 meters at the Prefontaine Classic and successfully defending her world championship title in Tokyo—returning to the same venue where she'd made her Olympic debut four years earlier as the youngest finalist.

Rogers doesn't just throw hammers—she's dismantling barriers. As a Black woman in a predominantly white sport, as someone who rose from housing insecurity to the Olympic podium, she's proving that excellence knows no background.

"What I love is seeing how much the sport's grown in such a short period of time. One of the most rewarding moments that I've had as an athlete and being involved in hammer throwing in particular, is getting messages from younger athletes and especially from moms who will just say, 'Hey, my daughter and I, have been like watching you and your progress and it's been so great to cheer you on and my daughter today told me that she really wants to try hammer throw out of nowhere. Do you know where we could try hammer throwing? Is there somewhere we could find like a track field club? 'I just get blown away because I remember when I first started, I had no clue what it was either. That very morning that I started it, I had no clue what the sport was and by 5:00 PM I was throwing a hammer."

Rogers regularly visits families supported by More Than a Roof during holidays, never forgetting where she came from. After winning Gold in Paris, she was able to tour her medal, visit friends and family, and host a meet-and-greet at her local track club in Richmond. “I got to see some of my old teachers from high school, who I hadn't seen since I graduated, which was so special. I loved all of them so much. It really takes a village and being able to have those experiences really grounds you.”

Rogers' story isn't just about sports. It's about what happens when a community invests in a child. When a mother refuses to let circumstances define her daughter's future. When a 12-year-old shows up to something new and finds belonging, when talent meets opportunity and relentless work ethic.

At 26, Rogers is planning for her first year without major championships since the pandemic. No Olympics. No World Championships. Just time to work, to learn, to prepare for what's next. Because champions aren't made in competition, they're built in the quiet moments between the roar of the crowd.

She hopes to share her experience, pass it on to other people, and encourage others to get involved with both hammer throwing and sports. But more than that, she's living proof that your circumstances don't get to write your ending. You do.

By

By