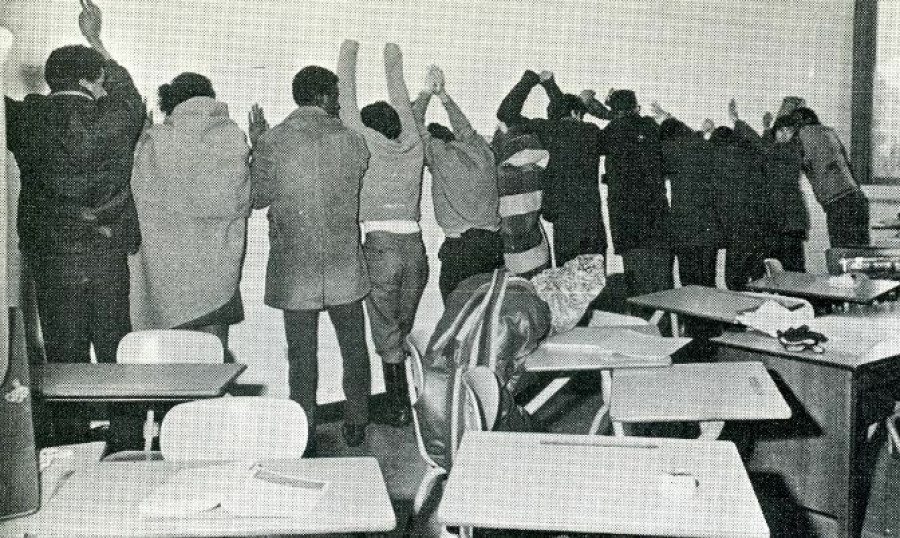

Also not easily recalled would be the attempt to set a group of Canadian university students (primarily from the Caribbean) on fire. But this is what happened in Montreal, 1969. Student protestors at the prominent Sir George Williams University accused Professor Perry Anderson of racism and a chain of events led to them being cordoned off in a ninth-floor computer lab that quickly filled with black smoke. This is history National Film Board (NFB) producer Selwyn Jacob never forgot. And for 40 years, he has wanted to document the riot for the screen. At this year’s Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), this powerful yet haunting entry from Canada is making its world premiere.

Producer Jacob was a recent Caribbean immigrant to Canada four months before the Sir George Williams University incident and says, “I could easily have ended up in Montreal alongside those students.” Forty years later, and now a producer with the National Film Board of Canada, he was finally able to bring this story to the screen.

“It’s not a flattering portrayal of the country,” says Jacob. “You have to do it in order to grow as a society and as a country. It would’ve been impossible to get a film like this programmed at the time this happened.” In 2013 he and veteran director Mina Shum (Double Happiness, Drive, She Said, and Long Life, Happiness and Prosperity) began production on what they both agree is “a national historic Canadian story.”

The film team managed to assemble a number of the players who still live with the pain of essentially being set on fire. It was 1969 and after a couple of weeks the nearly 100 students protesters were whittled down to six students signing their name to a formal charge. “Charges of racism from students? This was very un-Canadian,” says Shum, who admits she was shocked that she had never heard of this story.

Jacob adds, “We did a test screening in Vancouver of the film and 95% of the audience had never heard of it.”

Shum was set on filming “a very important part of our history. With racism, if we aren’t able to talk about what happened, we are not going to move past it in any relationship.” Shum, born in Hong Kong, arrived in Canada at nine months old. When explaining to her seven-year-old son that she was leaving for six weeks to direct a film she said, “I’m doing this for my father who endured racism, because he didn’t know the language and had ‘yellow skin.’ I’m doing this so this won’t happen in your lifetime.”

It becomes clear while listening to the gripping tales of those who experienced the events first-hand that the film is a necessity for these interviewees who remember 40 years ago as if no time has passed at all.

Jacob recalls that Senator Anne Cools, the first Black person appointed to the Senate of Canada and the first Black female senator in North America, wanted nothing to do with this story. Jacob says since Cools had spent four months in jail because of the Sir George Williams University Riots, she felt this shadow lurking in the background. “It wasn’t an easy sales job,” says Jacob. “I wrote to her, Mina spoke to her, Pat Dillon [publicist] spoke to her….” The film team conveyed their intention not to retry the case. According to Jacob, this was an opportunity to analyze how the country was and how the country has changed. “To get to a point where we can talk sensibly and with a sense of maturity in how we deal with racism. We can grow from the incident,” says Jacob.

Through archives and some clever casting to give voice to those too traumatized to speak—on both sides of the incident—the Ninth Floor is also an impressive accomplishment in its aesthetic design.

Director Shum credits her fascination with crime novels as influencing the film’s overall look providing a large part of the suspense. The survivors, whom she refers to as “the protagonists,” provide blow-by-blow accounts of an incredible story that Shum and her production team, led by the gorgeous cinematography of John Price, artfully reveal as a simmering burn.

“The antagonist is the university as a whole,” says producer Jacobs.

“The antagonist is also societal. I think the root of it is our capitalist society,” adds Shum. “Racism wouldn’t exist without an individual needing to have power over another individual. We should actually share that space. Through race, we devalue humanity and we value power.”

Shum’s use of space works to her advantage. One by one at the scene of the crime, a series of these former students unafraid to testify to their harrowing ordeal bring a palpable apprehension with every detail. Shum—who chose to forego actor recreations—says she and production designer Elizabeth Williams worked specifically on colour palette, texture and shape to establish a moody feel of the set, which harbours a sense of danger lurking nearby. “It was really important to create an environment for the participant,” says Shum. “We designed a sort of surveillance room set and deliberately painted windows so we could not see out of them. It provided a sense of mystery.” Shum says in order for the participants to feel ownership, she and the team showed them where the hidden cameras were. “We did this to pay homage to how they must have felt under surveillance.”

Figures such as Rodney John, Robert Hubsher, and Senator Cools to name a few, exemplify defiance in the telling of their story seamlessly punctuated with a treasure trove of archival footage. This reflection of their younger selves as optimistic rebel rousers was hardly cause for threatening the lives of students, far from home who wanted a fair shot at an education. Also caught in the archives in an embarrassingly unintelligent interview is a “faculty association” member who may have summed up what the late 1960s had in store for immigrant students. “The manner of West Indians are large gestures,” he says, and describes the behavior of laughing “immoderately” and the use of “picturesque language,” some of which he reduces to being “frequently obscene.”

The filmmaker's gift to viewers of this film comes in the form of a young talent, Nantali Indongo, who has an indelible link to the story that is clearly stated through her rendition of a signature Bob Marley tune. She also plays prominently in a scene so well choreographed in a busy Montreal train station, that Shum as a director credits the success of such a complicated shot to the limitations of a documentary crew of six and the insatiable persistence of production manager Dan Emery. The result: A powerful on-camera meeting of the generations without uttering a word.

Indongo’s presence in the film ushers in the future from which a Sir George Williams University incident may evolve: Damaged, but full of hope. Says Shum, “These students grew up to say ‘I’m going to figure out a way to keep agitating and change the world.’”

Jacob says, “There was a lot of shaming of the students at the time. Parents were ashamed of their kids. As a Black person, you don’t want to be judged or associated. They risked the parents never speaking to them if they chose to do this.” He adds, “There’s vindication for the students in this film.”

The filmmakers do not shy away from the questions surrounding Professor Anderson and how the incident affected his personal life as well. The journey that begins with who started the fire incidentally leads to a thorough examination of whether there was in fact racism at this university.

“Ninth Floor is the darkest film I’ve ever made,” says Shum. The feature marks her debut as a documentarian. “It was very emotional for me. I really had to look into the abyss here and go ‘Oh wow… humanity has a way of being cruel to each other.’” Shum says she has never cried as much shooting a film as she has with this one.

“I never let this one lapse,” says Jacob of his 40-year marathon to see this film through. “By waiting for those 40 years, you talk about life experiences shaping the film—there’s no doubt that racism persists. But Canadian society has evolved since 1969, and in many ways, it’s a different country now. The fact that the National Film Board is producing this film with Mina Shum as director and me as producer is one important measure of how things have changed.”

Show times:

Saturday, September 12th | 7:15pm | Scotiabank Theatre

Monday September 13th | 2:00pm | TIFF Bell Lightbox