Described by journalist turned filmmaker Jihan El-Tahri (Cuba: An African Odyssey, Frontline: House of Saud) as a “Modern Pharaoh,” Nasser headlines a 97-minute film, titled Nasser, and presented as a mix of historical footage and rare interviews over El-Tahri’s clear and academically sound narration.

Nasser fits the profile of an extended newsreel but with much more grit. Far from the cinema-verite style following the rise of an underdog often programmed in most festivals, this nonfiction experience takes the audience through a detailed explanation of military rule, the political ambitions of both the Communists and the Muslim Brotherhood and the genesis of Egypt’s industrial prominence.

Regarding “entertainment value,” Nasser is not the go-to choice, but it is an extraordinarily necessary piece of work for those monitoring the direction of modern-day Egypt. This programming choice was where TIFF took a chance—and it paid off.

Upon acceptance into the festival El-Tahri says “I didn't quite expect it. My assistant is the one who submitted. I didn't think of submitting to the ‘A festival.’ ” The film premiered to a standing ovation. “It was amazing! The cinema was packed. I was blown away by the extent of the response,” says El-Tahri who was very aware there would be a number of Egyptians in the audience watching a film that dissects an “extremely loved, major hero.”

President Nasser

Nasser died at 52 years of age. During his rule, which began after a peaceful coupe, he navigated the political relationships with both superpowers of America and Russia and Egypt’s involvement in the 1956 Suez Crisis and Six-Day War. Through scenes of victory and defeat, El-Tahri’s script very much aligns with the hypothesis she poses in the beginning: Will Egypt’s leaders be its liberators or its oppressors?

“I vowed to myself that I would never touch Egypt with a pole. I always break my promises,” says El-Tahri who begins the film in the aftermath of a revolt. “I saw an old picture which I never found again to put in my film (I was livid),” she says, “The picture was taken in 1951 right before the revolution in ’52. The placards read ‘Bread, Food and Social Justice’ which were written on the same signs we were walking with in the protests of 2011.”

El-Tahri notes that although Nasser is known as the founding father of modern Egypt, and is one of the leaders who conceptualized pan-Africanism and pan-Arabism, there was only a small moment of independence while the country was in transition. Nasser’s story—though triumphant in some aspects of establishing the country’s identity—documents a failure of post-colonial governance.

“There was so much hope after national independence in the 60s,” says El-Tahri. “We were creating a new world, but on the foundation of the world that was on the foundation of the old one.”

In spite of Nasser’s best efforts—a career military leader and eventual co-founder of the Non-Aligned Movement—his legacy, though complicated, may have inspired those who succeeded him.

El-Tahri spent five years, even spiraling into debt to finish this film, all the while knowing this was only the first of a trilogy: “My documentary is trying to follow the thread of how visionaries fell into the trap of dictatorship. It is the first of three parts: Nasser, Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak.”

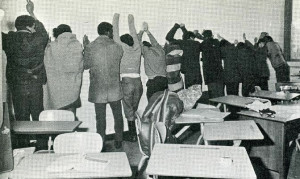

Revolution 2011

El-Tahri notes that her proposed trilogy represents the “dance between the military and Brotherhood since the beginning of the revolution in 1952.” She says, “We're at the crossroads and although the actions from Jan 25, 2011 have been totally crushed and silenced, in its place are the exact same group of people we revolted against.”

Through El-Tahri’s 30-year career of impeccable work as a researcher and interviewer, her Nasser audiences receive first-hand accounts from founding members of the Muslim Brotherhood, testimonials from Nasser’s allies in the Free Officers Movement and on-camera revelations from a number of top officials.

The investigative nature of her work has seen her banned from Egypt “for 18 years with only a week per year in my own country.” Unstoppable, her work philosophy involves bypassing man/woman-on-the-street interviews and “finding out what’s happening upstairs. It’s a small clique but I learn why and how decisions are made. This is the clique that decides our fate.”

For those who are interested in how she is able to get such powerful individuals of high rank to talk? “I talk to people for a year before I stick a camera in their face. I know more about them than they remember themselves.” Thus, El-Tahri notes the inevitable, which is less question and answer and more reminiscing about very specific moments.

“I do films that are heavily archive-based—archives that have never been seen before,” says the prolific filmmaker. “I find all the people everybody thought was dead. It’s time-consuming, money-consuming in-depth work where there may be no space for it.” But for El-Tahri who spends her off-hours as a club deejay and finds the enthusiasm and energy of Egypt’s young people spurring her on, says she knows why she does it.

“There is an often-quoted Zambian proverb: When the elephants fight, it's the grass that suffers.” Says El-Tahri, “The Egyptian people have been the grass forever really.”