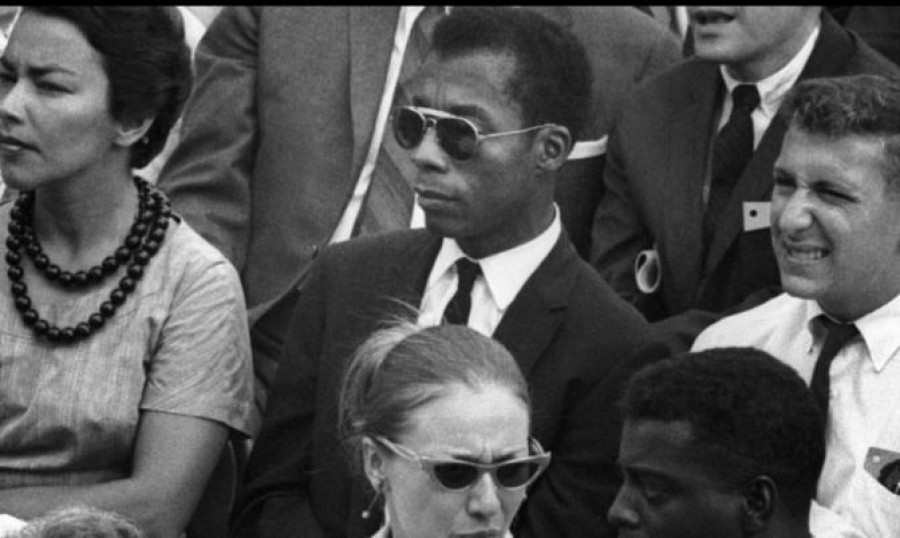

I love James Baldwin. With each poetic verse of an essay, text or (thankfully) archived filmed interview that through his eloquence affirms the power of prose it is easy to profess total devotion to experiencing the work that is the soul of James Baldwin (b. August 2, 1924, d. December 1, 1987). Once you meet Baldwin through any of his writings such as The Fire Next Time, Notes of a Native Son or Giovanni’s Room, you are under his spell.

I tell this young man that for Black Americans in the United States there would be no hope of understanding and overcoming the troubled history of race in America if it were not for the ex-pat whose writings and gripping commentary never wavered in his love for the sisters and brothers he championed.

Listen to the audio version of this article:

Nova Scotia Filmmaker Sylvia D. Hamilton remembers, “When I was making Speak It! From the Heart of Black Nova Scotia (1992) a short doc about Black youth, racism and empowerment, I began the film with a Baldwin quote: ‘Black people need witnesses in this hostile world which thinks everything is white.’”

Hamilton is a descendant of Black Refugees who settled in a rural community of Nova Scotia as a result of the War of 1812. “My ancestors, the Hamiltons, took their own freedom by escaping from a plantation somewhere in Georgia. They got themselves behind the British lines and eventually sailed to Nova Scotia in about 1814.” Hamilton’s films are celebrated for enlightening audiences with the brilliance of Canada’s Black pioneers coupled with the blunt reality of obstacles the communities had to navigate to actually thrive. She found warmth and inspiration in the books of Baldwin: “James Baldwin remains a touchstone for me. When I bought those books, I had no idea what he looked like because I had never seen his photo. Then, some many, many years later I saw his wide, enchanting smile, and there it was: a wide gap in his teeth, just like mine, and that of both my oldest and youngest brothers.”

In his final years of life Baldwin wrote 30 pages of a book titled Remember This House. This precious text was Baldwin holding ever so close to his heart--in a very protective way--his three friends Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King assassinated in 1963, 1965 and 1968. This book was to remain unfinished.

"I think he did write it." As if on cue—a little more than 25 years later—in walks director Raoul Peck (Lumumba, The Man by the Shore, Fatal Assistance, Sometimes in April) who would spend 10 years piecing together Baldwin’s final attempt to tell the story of America. Says Peck, “For sure this film became concretely a «project » 10 years ago. But the previous 30 years with Baldwin [Peck first read Baldwin as a 15-year-old], were as important in shaping who I am today and shaping the film.”

Peck’s masterful storytelling of the literary icon who was affectingly aware of the human condition allows for scenes of an engaging interviewee, encompassed by visual essay (voiced by an unrecognizable Samuel L. Jackson), exposing a bigoted pop culture that fed into the imperialist nature often attributed to the U.S.

Part of this film’s legacy will be that it premiered at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) by invitation of Cameron Bailey, TIFF’s Artistic Director and longtime Peck colleague. TIFF’s documentary programmer Thom Powers, who oversees the TIFF Docs section where I Am Not Your Negro appeared has thoughts on why the film received a standing ovation and went on to win the Grolsch People’s Choice Documentary Award: “It’s not a case of a film being rushed out to fit current events. It has a timeless quality that would make it fitting for any year. But this year turns out to be an opportune time to hear the voice of James Baldwin. Too often, our media is preoccupied with what’s happening right now. It’s like a sickness that prevents people from taking a longer view for which this film is the antidote.”

Oscar-qualifying screenings in New York and Los Angeles accompanied by Peck, its astute and highly accomplished director, also provided many preview audiences a time for reflection and introspection. In New York’s Harlem, the film team programmed a walking tour of Baldwin’s childhood streets, with Columbia University Community Scholar and Harlem Historian John T. Reddick who sensed Baldwin’s ability to “not only expand the boundaries of his intellect, but also the boundaries of the physical city, beyond the narrow confines of his block and neighborhood.” Reddick walked his band of Baldwin enthusiasts to the front entrance of the community’s legendary Harlem Hospital: “Baldwin first meets Martin Luther King in 1958 while working on a Harper's Magazine article about King published in October, 1958. Well, in late September of that year Martin Luther King was stabbed and seriously injured during a book signing at Harlem's Blumstein Department Store.” Thus, threats that could be fatal for King would not be unfamiliar to Baldwin and King’s army of disciples. As we learn in Peck’s portrait, news of his friend’s demise—the third attempt to exterminate the civil rights movement—would knock the breath out of Baldwin.

Peck’s film shows just how much strength Baldwin displayed through his intellect to continually slay those with “moral apathy” who he calls out as the country’s “moral monsters.” Raoul Peck: “I have a favorite quote from Baldwin. ‘Every human being is an unprecedented miracle. One tries to treat them as the miracles they are, while trying to protect oneself against the disasters they’ve become.’”

There is a cleverness par excellence in Peck’s directorial feat that only the 10 years time and dedication could produce. So I had to ask him, “You grew up with Baldwin. You were intimately involved with his work for a decade while making this film. Now you've released it to global audiences. What are you going to miss now that you’re done?”

Peck’s reply: “Baldwin is not somebody you can « leave » behind. He was part of my life a long time ago and for sure will continue to be an inspiration, a bulwark against stupidity and arrogance, a source of wisdom and a political philosopher to whom you can always go back to for some solace and a poet who can always reconcile you with this crazy world.”

It would actually be a most ignorant move on my part if I were not to share with the next generation of #BlackLivesMatter that a filmmaker was able to take present-day news footage of Ferguson uprisings, photographs from the 1950s persecution of schoolgirl Dorothy Counts, images of a spirited people living under a cloud of systematic oppression, film clips from the #OscarsSoWhite cinema library, memories of an effervescent Lorraine Hansberry challenging and unmasking a flawed politician considered a civil rights hero, and much more to keep an audience of all races mesmerized while holding on to an ounce of hope even though the deaths of three civil rights icons would be waiting in the wings.

I Am Not Your Negro is a gift to the young man who never knew Baldwin—to us all. And, it comes with a footnote: Anyone new to Baldwin has to pay attention while watching this film, because Baldwin is not going to tell you again. Baldwin as prophet sends a chill to our bones. But if you listen carefully, and Peck directs you to do just that by immediately launching into Baldwin’s contemplation of a Black man’s optimism as possibly his burden, you experience the lesson in Baldwin’s resolve. Says filmmaker Hamilton, “His wit, his intelligence and his uncompromising analysis remain important to me. While some may be coming late to the Baldwin party, I am sure they will be glad they did.”

The film is scheduled for a theatrical release February 2017 and later in the year on PBS.