We had no idea where we would be at the end of the raging pandemic as COVID-19 upended our existence.

In the poignant documentary, Someone Lives Here, carpenter Khaleel Seivwright saw what was happening in his city. Due to the loss of jobs and homes, many Toronto residents were left in the cold as they wrestled to find somewhere to lay their heads. Shelters were high-risk and not as ‘safe’ as we would like to think they were. They were also consistently at 99% capacity, leaving those without refuge to battle the harsh winter elements. So Seivwright decided to take matters into his own hands with an idea he had been toying with for some time—his tiny shelters—an innovative, insulated, body-temperature heated mini-house for people experiencing homelessness to find refuge and solace.

“The idea was bubbling in my mind for a while. I lived in an off-grid community in B.C. on and off for about three years. I built something similar to the tiny shelter in this community to have a place to stay and for other people to use when I wasn’t there. But, then, coming back to Toronto, driving around to and from work, and seeing people in encampments, I had never seen that many people tenting in Toronto before. It was shocking. So the idea continued to bubble in my mind since March and April that someone could use this. And it was also partially for me. It was a place that I imagined I would love to hang out at sometimes.”

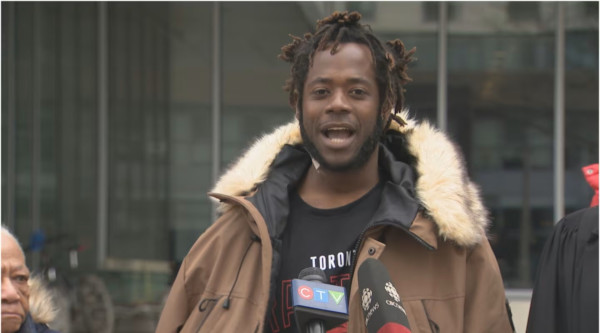

“I remember staying with roommates and telling them, 'Hey, I'm gonna go build something.’ No one understood what I was talking about. They were like, ‘Oh, that's cool. Yeah, right on (laughs).’ I was excited. At first, not many people knew about it. I started it anonymously and was trying to raise money to build more of them. It was a prolonged process. Only when it was picked up by CBC reporter Nick Purdon, who was jogging by a tiny shelter in the Don Valley and thought this would be a great story, that’s when it exploded. Then, we started making a ton of them. People needed something, and this is what I could do. I figured why not just do the thing that makes sense,” says Seivwright.

Unbeknownst to him, the media coverage would snowball into something extraordinary. And not just in Canada but internationally. However, when it finally received the attention of our government, things quickly went sideways. In one breath, it had the potential to become a collaboration with the City of Toronto. It’s difficult not to feel like said collaboration sounded more like a fact-checking mission delivered with a backhanded ‘I’m so impressed that someone like you did this.’

{https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EhFIRF4k7zA}

Then, only a week later, Seivwright was served with a legal injunction from the City of Toronto, ensuring a partnership was nowhere in sight. The onslaught of hurdles and emotions was a lot to bear. In the documentary, it’s easy to feel the heaviness of the load on Seivwright’s shoulders. Going against the institution (and Mama Seivwright) does come with costs. Nonetheless, there was never a moment when he was ready to call it quits.

“There were moments when I felt like, ‘ah, this is going to be bad,’ or ‘this is eventually going to get very bad.’ I didn't know how it would go, but as long as we were getting support to continue and there wasn't a legal injunction against me, I felt like we could keep doing this because it made sense to do so.”

“It was a ridiculous mentality that I didn't understand. It was all very illegal. But for some reason, it didn't cross my mind. I just thought, ‘This makes sense. I'll keep doing it.’ It didn't sit with me that this was illegal because it made sense,” says Seivwright.

What doesn’t make sense is the astronomical bill the City of Toronto paid to clear the encampments. 1.9 million dollars on cleaning up encampments in three city parks.

Tractors crawled at a snail's pace as police rolled in on a procession of bikes and horses. The mood was sombre and telling. Heavy and permanent. A simple job for some, yet a devastating outcome for many. It all played out on television as we watched violent police clashes, tactical gear, and muscle power clear out campsites. Compassion and understanding were null and void, and Seivwright didn’t understand the thought process behind it. Many don’t.

Read this: Jesus Was A Carpenter: The City of Toronto vs. Khaleel Seivwright

“Something that bothers me is the overall investment in these encampment evictions. It seems so clear to many people. But I don't know why it doesn't seem clear that when you pay many officers to move people around who don't have somewhere to be—what are you doing? You're paying someone money to displace someone, and they will be homeless somewhere else. It's not a solution. It's such a short-term mentality. I don't understand it. You have people in office who have been politicians for decades, and somehow they're advocating for this approach to homelessness. What is their idea of success? It doesn't add up to me that investing money in doing that continues to make sense," says Seivwright.

In Someone Lives Here, listening to one of the interviewees, Taka, discuss her story of homelessness and the crushing inhumane blows accompanying it is like listening to a philosophy class in the human condition. She serves as an endearing and wise sub-narrator in the documentary. Yet, on the other hand, hearing her voice and the perspectives of other displaced persons is a deep dive into an abyss of despair, sadness and authority.

After the snow melted and spring settled in, a new chapter began for Seivwright. After cleaning, reassessing and redirecting his energy, he had to recharge and reflect. “I was pretty overwhelmed, and overall, I felt very low afterward. I went to B.C. to live with a good friend for a few months. I went completely off the grid. I would wake up, make coffee on a propane stove and go for a nice walk. I was roughing it. I did it for almost nine months. I had this overwhelming feeling that I was doing something wrong or that there was something else I should be doing. When the chapter closed with Toronto’s tiny shelters, I felt like it wasn’t over, in a sense. There had to be something else to do other than just leaving. Then I came up with the idea of building camper trailers and using that as a sustainable way to raise money.”

{https://www.instagram.com/p/CmxNuRbv2jq/}

“I had the thought of combining building science with camper trailers. For some reason, building science has not been applied to camper trailers to make them thermally efficient as passive homes. Why not do that and have a thermally efficient trailer? That’s what made sense to me. That's what I'm doing now. I've never had my own business, so we're going to see how this goes,” says Seivwright

The premiere night for Someone Lives Here is already sold out. The documentary is a fantastic piece that gives the viewer a comprehensive look at Seivwright’s inner workings for his tiny shelters, alongside the lives of a few tiny shelter recipients. He eventually settled with the city and was prohibited from creating or placing his tiny shelters in public parks. Ideally, he wants to put his new camper trailers in tiny home communities. Talk about forward thinking. Perhaps if we could be more like Seivwright and see homelessness as a crisis rather than a burden, we can find ways to move forward constructively.

Where is the investment in affordable housing? How can programs reach the people they are intended for if said recipients don’t have cell phones to call hotlines? How can we find long-term solutions rather than applying a band-aid for a temporary fix? Even Hamilton, Peterborough, and Bellvue have tiny home communities that assist in helping those in need. Kitchener’s A Better Tent City has a community-based approach to assisting residents facing chronic homelessness. Could that be a model that works in Toronto?

As Seivwright says throughout the doc, “It doesn’t make sense. It just doesn’t add up.”

These are all valid questions we’ve been asking for a while now. Seivwright will always be remembered as the guy who willfully did what he could with what he had, and that, I’m sure, will never be lost on many.

As Derrick Black, a Moss Park encampment resident, the first to receive a tiny shelter, states, “I hope the city can see what we’re fighting for and help poor people. There are a lot of people on the street that need places. We want the same thing the mayor has. We want our own key. That’s what everybody is looking for, a place someone can call their own. It doesn’t matter. A home is still a home.”

Someone Lives Here has a second screening on May 4th at Hot Docs Festival, you can also stream it on the Hot Docs website from May 5 - 9.

By

By