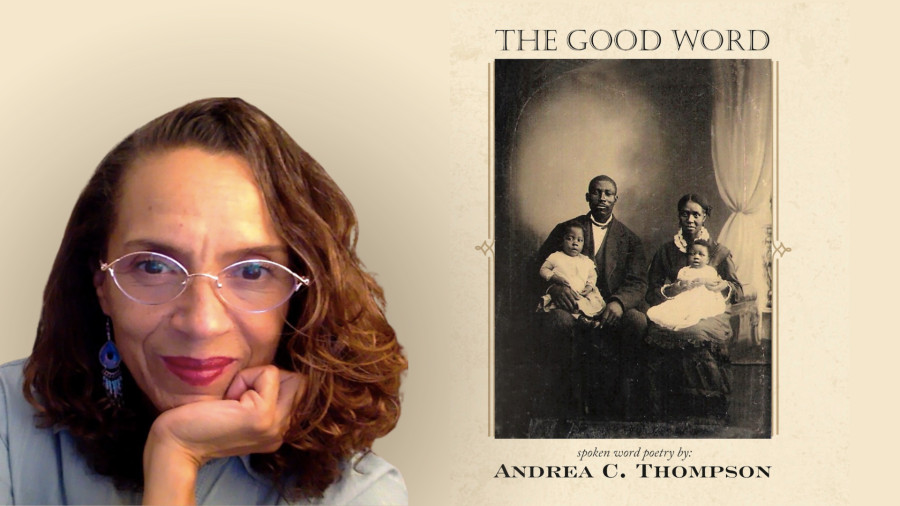

Highly decorated, award-winning Black Canadian storyteller, spoken word poet, and professor Andrea Thompson is leaving an exceptional legacy worthy of a review. And it seems she’s following in the footsteps of her ancestors too. Thompson’s paternal great-great-great-grandfather, Cornelius Thompson, was enslaved in the United States, but he made Canada his home via the Underground Railroad. In her latest spoken word album, The Good Word, Thompson delves into the experiences of silenced Black voices by unfolding questions of faith, race and reparations discovered through his journey. She also uses music, particularly jazz, blues and negro spirituals, as her accompanying tools to expand upon and deliver her stories. It’s a solid outing as she investigates how our Blackness in Canada resonates within ourselves.

Thompson grew up in an environment surrounded by poetry, music and literature. With the influence of her grandmother and grandfather, Thompson was exposed to the power of the word. From Shakespeare to Coleridge and her love of jazz, she knew all those worlds would collide one day. “I always thought that poetry was about an oral art form. Also, I sing as well in my specific style of spoken word. Singing is something I have always loved. The other thing that was a constant in my household growing up was jazz. I grew up listening to Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong and all the big bands. Especially listening to female voices like Billie Holiday. Women's voices singing around the house were a constant.”

{https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZK9O4VOBc4}

“And it's funny how I started singing. I was in my twenties or something, and I wanted to be more cool (laughs). I wanted to bring some hip hop vibes to my work. So, I knew I wanted to bring in musicality, and then I opened my mouth and out came this jazz cadence. I wasn't even a jazz fan at the time! I realized, oh, I'm terrible at hip hop (laughs). But I think it had that sense of musicality that had been in my blood and bones, and it just came out,” says Thompson.

Her resume speaks to the respect and accolades she has received over the years. Here is the condensed version: Thompson was a member of Canada’s first national slam team and featured in the award-winning documentary, Slamnation. She was also the host of the critically acclaimed Bravo TV series Heart of a Poet. In 2021, Thompson received the Leon E. & Ann M. Pavlick Poetry Prize. Additionally, she is the author of many essays on spoken word, has taught many poetry workshops and has designed and continues to teach the first spoken word full-credit course in the English and drama department at the University of Toronto (U of T). This is simply the tip of the iceberg.

“Canada is a bit behind. In the U.S., the top Ivy League schools like Harvard and Stanford have taught spoken word for the last 10 years. It's taken a while for Canadian universities. Before I taught at U of T, I taught a continuing studies course at Ontario College of Art & Design University (OCAD). And OCAD has since developed a comprehensive spoken word program. So they were really leaders in that way. But in terms of U of T, definitely in this English and drama department, it's their first course. So I'm very excited,” says Thompson.

All of these successes for Thompson add to the trajectory of spoken word in Canada. Especially since Black stories are being taught via multiple projects and schools, our storytelling is at the forefront. Like the influences from the United States, Thompson has worked tirelessly to bring our stories forward. But she also explained why Canada still needs to play ‘catch up.’ “I think it's a numbers game when you look at it in terms of influences. The thing about spoken word and what I've been writing about academically as well as in my last book, I guess I touched on it a little bit by inference on this collection, The Good Word, is the idea that spoken word, specifically in Canada has been influenced by this history, by Black history and culture, going back to slavery.”

“So we've got slavery and call and response. We've got covert communication using languages and covert communication. It starts there in North America. Then we've got the Harlem Renaissance in the twenties and the Black Arts Movement in the sixties. And so all of these things are happening in the States. I've ended up writing about contemporary spoken word Canada in the influences of Black history and culture. I've written mostly about the States because that was where our lineage came from. There's just a bigger Black population in the States who did what I did at U of T, just went and knocked on the institution's doors,” says Thompson.

Just like Sonya Sanchez at the doors of the University of California in the sixties, Thompson knew the existence of a program of this magnitude was a need. And her work continues to explore the Black population specifically. Focusing on our dominance and understanding of oral tradition, The Good Word came to fruition through her innate curiosity and many years of research. “I remember when I was a teenager, we would go to the country in the summertime for the schoolhouse reunion. And it suddenly dawned on me. I wondered, ‘how come everybody in the country is Black?’ What’s up with that? (laughs) I wasn't being taught Black history in school. So I didn't know it, and I took it for granted. Then I started learning. People decided, let's educate her about where she came from. So they gave me books and told me stories, and I've been learning through the years,” says Thompson.

And learning about her great-great-great-grandfather's life was both a history lesson and a moment for self-reflection. Both instances add to the album’s experience and Thompson’s life. Knowing where he came from and the person he was in correlation to who Thompson is and the woman she’s become. It was humbling for her and can be planted as a seed and life lesson for us all when listening to the album. We’re all human, and our life stories will be a part of our lasting legacy.

“He was a brave, amazing, larger-than-life human being. I heard he had a big afro and escaped slavery, so I had this mythological and heroic idea of him. And as I was doing the research, I found out other things. Things like, he left without his wife. And I said, okay, that's complex. Then he had somebody else write letters back home to try to find her because he couldn't write to or find her. He later started a new life, and I heard he wasn't very nice to his kids. I asked myself, do I put that in there? Is that disrespectful? And I thought, no, that's human because that's one of the woundings of slavery. He had his own complex challenges,” Thompson recounts.

“So I think, for me, comparing myself to him, there are times in my life when I've been heroic and had to deal with things all on my own. A little brown girl in a white environment who decided, ‘I'm going to be a poet’ as a kid and then tried to make a career out of that. How did that happen? That's an impossibility! (laughs) But here I am, middle-aged, and I haven't starved to death, so something worked out. I can see that overcoming the odds element in my own life and feel proud of it. At the same time, though, I can also see that I'm human, and there are times that I've gotten on the wrong path or haven't taken the right approach, but I think that's what it is to be human. And that's how I decided to tell his story. I wanted to include all of what made him a human being because that's the journey we're all on.”

This story is part of our “Women’s Month" series, where we celebrate the remarkable journeys and accomplishments of Black Women In Canada.

By

By