It is currently on stage in Toronto at the Princess of Wales Theatre (for a second time) until April 16.

A few weeks ago, I saw the show with friends. During (and after), I was deeply bothered by it but I could not fully explain why.

Was it the black genital jokes? Or, was it the mostly white audience who found such jokes funny?

The show, widely lauded by critics, is set to hit the stage in Denmark and Norway later this year. As far as mainstream media (and audiences) is concerned, Book of Mormon remains a hit.

So, why am I writing this now? What else can possibly be said about it?

My issue with Book of Mormon extends beyond the theatrical stage.

To focus exclusively on the play without considering the cultural context of its reception allows fans and critics alike to reduce its offensive content to mere entertainment. There are deep seated reasons why, primarily white audiences, find Book of Mormon entertaining in the first place.

Scholars such as Svetlana Boym have argued that American popular culture has become a common coin for the new globalization, that is, its products mask cultural differences behind visual similarities. Like other forms of American popular culture, Book of Mormon is endemic of a return to drawing viewers into the cultural differences and visual similarities between past and present sites of colonialism.

For example, advertisements for Louisianatravel.com, the state’s official travel authority, have started appearing in buses across Toronto. These ads pair food such as gumbo, with sprawling plantations, creating a semiotic relationship between culture, (presumably white) tourists, and a history of black servitude.

In The Wounds of Returning, Jessica Adams explains that the new plantation economy of the South invites tourists to view themselves as slaves (without the brutality of slavery) and also as masters (without the visuality of said brutality) in the act of returning to the plantation.

Book of Mormon, I would argue, does the same thing.

It invites audiences to view themselves as pure white missionaries (even as Mormonism is satirized) but also as immoral black Africans (Uganda as a stand-in for Africa), creating a seamless ahistorical narrative about the “natural” differences between both groups.

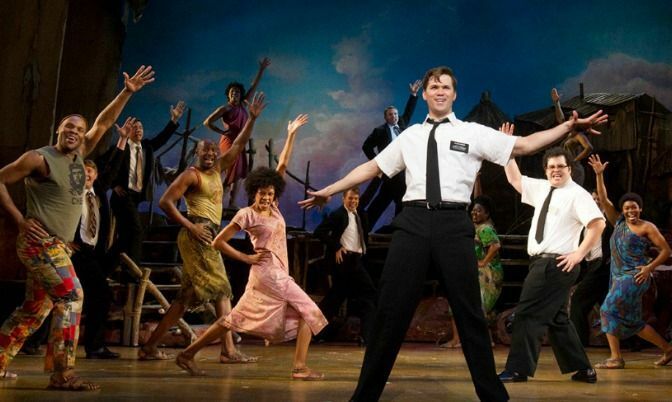

The show begins at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Missionary Training Centre in Provo, Utah where we meet its protagonists, Elder Price and Elder Cunningham, who are set to embark on a mandatory two-year mission to spread the word of Mormonism.

In the first musical number, “Hello!” we are introduced to Price, the successful straight man, and Cunningham, the overweight (and flawed) comedic foil. In the second musical number, “Two By Two,” we learn of Price’s dream to carry out his mission in Orlando but that in reality, he and Cunningham will carry out their work in a small village in northern Uganda.

The narrative of Book of Mormon is centred on Uganda (though its advertising omits this fact), where Price, but mostly Cunningham, convince the Ugandans to accept the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as their saviour and to convert to Mormonism.

Outside of being offensive and crass, this story is a not-so-subtle re-packaging of a lauded nineteenth-century colonial novel, Heart of Darkness.

Written by Joseph Conrad, the book explores a voyage to the Congo, while drawing a line of difference between European travelers and African villagers.

As Nigerian postcolonial writer Chinua Achebe once noted in his 1977 article, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness,’” white racism against Africa is such a normal way of thinking that its manifestations go completely unremarked.

Where students and scholars of the book often argued that Conrad was concerned not so much with Africa (and Africans) but with the deterioration of the European mind caused by solitude and sickness, Book of Mormon’s defenders have similarly said the play is not so much about Uganda but a satirical parody aimed at Mormon do-going.

If the play was set in Utah, then this argument would make sense; the backdrop is, however, in Africa as it is about Africans.

In the first Ugandan musical number, “Hasa Diga Eebowai” (a phrase that supposedly means “Fuck you, God”), Elder Price and Cunningham arrive in Uganda, only to lament that their luggage was stolen, the plane was crowded, and the bus was late, that is, Africa lacks the civility “naturally” found in America.

When the Ugandan villagers enter the stage, they are singing and dancing about the darkness of their homeland – its poverty, starvation, drought, and village leader Mafala even sings that the vast majority of the people have AIDS. The “evil” Ugandan warlord, who threatens the villagers with female circumcision and sexual intercourse with babies, also embodies this darkness.

Some people who read this will argue that I have completely missed the point of satirical parody – it’s not meant to be taken literally, it’s just a joke. Well, a lot of people I know who have seen the show did not find it funny at all. In fact, they were left just as shocked as I was by its contents, but even more so, by the joy expressed in the audience.

If Book of Mormon returns to Toronto for a third time, we really need to question the audience’s appetite for returning to the warped belief in the “darkness” of Africa for popular consumption.

By

By

![[REVIEW] Young People’s Theatre’s ‘Mary Poppins’ a must-see for the holiday season](/media/k2/items/cache/71a42ae7863301ba46b5e226eaecf171_M.jpg?t=20181122_183641)