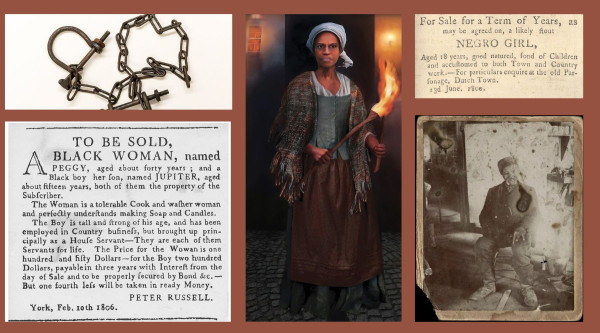

Bashir Mohamed researches and curates an ongoing archive of black history, discrimination and racism in Alberta. It’s an interactive archive that lives on his Twitter account.

“Twitter, for me, was a good medium,” Mohamed said. “Whatever I came across wasn’t behind a wall, it wasn’t an academic article. It’s in plain language that anybody can understand.”

Mohamed wants to make it clear he’s “not a historian.” Instead, he says he’s someone who has found holes in what people are being taught.

“I grew up in Alberta,” he said. “I was here from elementary [school] all the way to university, and I never learned about this history.

“When I started looking into the archives, I wanted to find an accessible way to share it.”

Mohamed’s use of Twitter is unique in that it allows people to interact with and easily share his findings. He says he has even effected change since he started doing it more seriously.

“Because of the attention, a lot of this got, publications have asked me to write for them,” Mohamed said. “The [Canadian] Encyclopedia asked me to write an article about a civil rights figure — Ted King — who fought against segregation, so, I did.”

Mohamed says his work has also had an impact on developments in Alberta’s legislature.

Bill 206, or the Societies (Preventing the Promotion of Hate) Amendment Act, was introduced by Craig Coolahan, the NDP MLA for Calgary-Klein.

“That came from an MLA reading one of my articles,” said Mohamed.

Mohamed says he’s not the only person who believes Canadians need to be better educated on black history.

“Most Canadians want to learn about it and take action and make sure it’s reflected in our curriculum,” he said.

A University of Alberta political science graduate, Mohamed is a public servant who works for the province and a freelance writer who contributes to publications spanning the country.

The Somali-Canadian’s family arrived in Canada in 1997 after fleeing the Somali civil war. But before coming to Canada, they spent six years in a refugee camp in Kenya, where Mohamed was born and raised.

Mohamed says he’s been a victim of racial abuse. A few years ago, a racial slur was yelled at him while he rode his bike through Edmonton’s Ice District. He recorded the incident and shared it with people, generating a lot of attention and reactions.

Mohamed says some people expressed shock that such racism could exist in Canada.

“That made me question if that was true,” he said. “That’s why I did some of the initial research.”

It was then that he found cases like Charles Daniels’.

“He was a black Calgarian who was refused access to a theatre in 1914, so he sued the theatre and actually won the case.”

Lulu Anderson was “a black woman who did the same thing in 1922,” said Mohamed.

What shocks him the most? “Seeing the institutional support [for racism] in Alberta.”

Mohamed found significant information about a notorious white supremacist hate group’s historical activities in Edmonton. He said the Ku Klux Klan, “which had somebody in the mayor’s office in 1931, approve cross burnings.”

At the City of Edmonton archives tonight. Came across this photo showing Edmontonians watching a speech by Klan leader JJ Maloney.

Interesting how they labeled it a 'Free Speech Special.' pic.twitter.com/tCiOrGojZl

— Bashir Mohamed (@BashirMohamed) February 8, 2018

Mohamed found that the group was provincially recognized by the Alberta government as a society until 2003.

“The height of their power was in the 1920s and 1930s, and that’s when they had supporters that occupied the mayor’s office,” he said. “They had MLAs that supported them and approved cross burnings.

“They had another phase that started in the 1980s which was more militant, in the sense that their leader was more aggressive.

“They were formally recognized as a society, and they were approved again by the government. The only reason their status as a society was discontinued in 2003, was because [they] didn’t re-file financial documents, and their status expired.”

The idea that groups practice beliefs that involve discrimination is what baffles Mohamed and motivates him to continue sharing this ongoing history.

“This is not something from 100 years ago,” he said. “This is fairly recent. We have a lot of far-right groups in Edmonton: The Soldiers of Odin, Proud Boys, and a few other groups.”

Watch below: (From January 2019) Edmonton police said their hate crimes unit was called in to help investigate after a prominent and well-attended mosque in the northwest part of the city was visited by a group whose activities are known to police. Albert Delitala reports.

His work to uncover and share this history is part of a movement that he hopes will ultimately lead to a lasting impact on education.

“The first step to solving a problem is understanding that there is one,” Mohamed said. “By ignoring it, we’re effectively whitewashing it, and it’s becoming more difficult for us to address systemic problems like inequality in our justice system and [in] education.

“In Canada, we assume these are not problems, so we don’t look into the history or the data.”

Mohamed has also looked into data on policing and how often minorities get carded compared to white people in Edmonton.

“We don’t have the data, so we don’t know the scale of the problem, whereas in the [United] States or other provinces, they do,” he said.

People have taken note of his Twitter account, and with over 10,000 followers, Mohamed has stirred up mixed reactions, however, he said, “the vast majority are positive.”

Teresa Zackodnik is an English studies professor at the University of Alberta. She teaches courses to do with black history and feminism and said she follows Mohamed’s Twitter account.

“He’s giving us the history that we absolutely need,” she said. “We don’t want to be naive and think we’re past racist periods in our historical past. We want to understand the connection between the moments we’re in now and the history that underwrites them, that makes them possible.

“Bashir is able to do that.”

Zackodnik said she thinks Mohamed’s use of Twitter lets people engage. She also said it displays bravery.

“It’s by no means easy or comfortable work, so when people are interacting with it and him, there’s a pretty dark side to it,” she said. “That’s significant labour all on its own.

“People are really being challenged by what he is publishing.”

Mohamed said although his work receives mostly positive reactions, there are negative ones too.

“The negative stuff is usually people who send me threats or call me a racial slur,” Mohamed said.

Because of this, he says he’s had to take security precautions while in public. Mohamed said it makes it feel apparent to him that racism and discrimination is alive and well.

“There hasn’t been an end point where racism is over,” he said. “I think a lot of people look at history and think… ‘Yup, this is where the bad things happen[ed] and then things got better,’ but that’s not necessarily the case.

“A lot of people who face segregation or formalized discrimination are still alive.

“There’s no hard point where something becomes the past. It’s all living. History’s not dead. It’s a process that is very active, and we all engage in it. To do better, we need to a) acknowledge that by implementing curriculum, and b) be open to challenging some of these assumptions we have.”

Mohamed said he wants others to know they can do what he is doing as well.

“I’m just one person,” he said. “I don’t consider myself a historian or an expert.

“If somebody is listening and they want to do this kind of research, they would be in the same place I was two years ago. It’s not just one person who changes things; it’s a community.”

Originally published on Global News.

By Taylor Braat - Global News

By Taylor Braat - Global News