Home is about community. It’s about feeling like you are a part of a family. Home is where you want to be.

For me, home is always where I feel the most safe and secure. Growing up, it was the smell of Caribbean food wafting through my parents’ house and hearing stories of their childhood in Barbados. It was where my friends and I shared dreams and cracked jokes. Home was where I could be my authentic self without worrying about what anyone else thought.

I was born and raised in Canada, specifically Montreal. Being raised in a West Indian household, my parents would always talk about ‘going home.’ Going back to the place where they grew up – where they didn’t feel othered by a country that didn’t accept them because of their Blackness.

So, as a child, I would ask, “When are we going home?”

My mother would laugh. “Home? You’re a Canadian. This is your home.”

Although my navel string is buried in Canada, I never felt Canadian enough. I’ve had teachers say I wasn’t going to amount to anything for no other reason than I was a Black kid in a predominantly white city. My experiences of anti-Black racism in my country of birth made me yearn to connect with my roots.

While Barbados is the home of my direct descendants, hearing my parents laugh when I called Barbados home made me feel caught between two cultures.

I feel like an immigrant when I’m in Canada and I feel like a foreigner when I touch down in Bridgetown.

I felt homeless.

For many of us who are children of Caribbean immigrants, there is a disconnect. Where is home? Is it a place that welcomes you with open arms or is it where your ancestors came from?

A few years back, I did an AncestryDNA test. I did have concerns about where my genetic material would end up, but my desire to know and understand who I was superseded that. The test results sent me to Nigeria, Ghana, Togo and Benin. Not surprising, but exciting. So, when I was offered an opportunity to travel to Ghana with a group, I was ready to pack my bags and go.

And maybe I’d find a type of home.

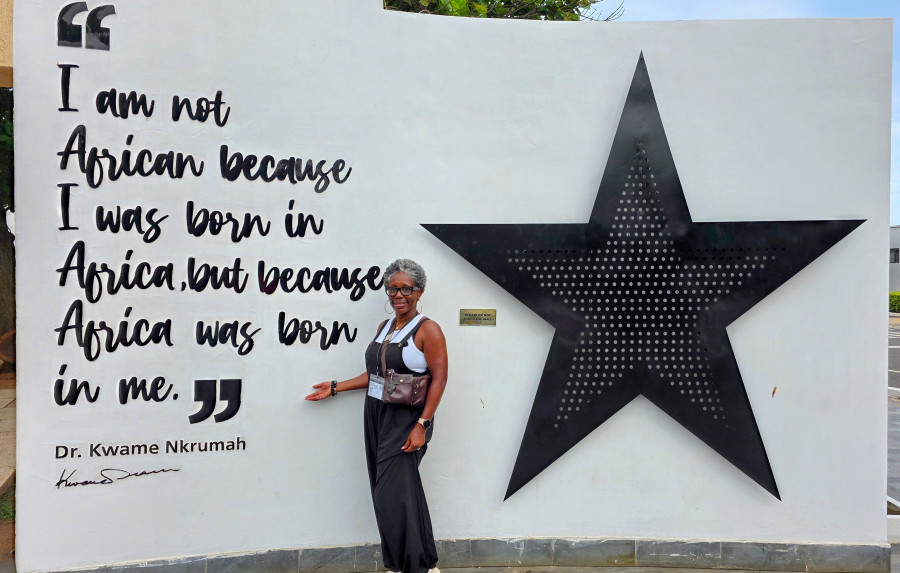

After 15-plus hours from Toronto to Accra, I stepped foot on the Motherland. I hoped that this pilgrimage would be the missing puzzle piece of who I am and where I belong. Maybe it would fill a gap and help me heal from the hurt of not feeling accepted.

But that’s not necessarily what I got.

When I stepped off the plane, Ghanaians welcomed me with ‘Akwaaba’. Everyone from the taxi drivers to the children who ran around the town we stayed in, told us how happy they were to see us come back home.

Back home.

I saw The Door of No Return at Cape Coast Castle that my ancestors were forced through as they shuffled, chained together, onto slave ships. And then I came back through The Door of Return, which welcomes the descendants of enslaved people back home. I wondered how I would feel about home, if my ancestors had not been stolen.

Most of the people I met on my travels throughout Ghana opened their arms to me, but some didn’t see me as their long-lost sibling. I was oburoni, the Akan word for foreigner that means, “those who come from over the horizon.” While there were greetings and ceremonies to welcome us, there were the tuktuk drivers triple-charging us or the chief who wanted us to buy land because we were rich Westerners.

Layered into those interactions were the moments when we were called ‘selfish,’ ‘greedy,’ ‘Eurocentric,’ or ‘privileged.’

I hoped to feel an instant emotional connection and belonging, but I didn’t. Ghana felt like a distant relative.

During the trip, I had a brief conversation about DNA tests. The Ghanaians we spoke to laughed at the idea of DNA deciding who is African because, for them, identity isn’t individual. It’s lineage and the clan you can name out loud.

“What is your last name? You don’t know your real name,” one of them asked. “I don’t know the tribe you belong to. DNA says you are from Ghana, but borders meant nothing. It was your tribe.”

I thought touching Ghana’s red soil would feel familiar – that my DNA results and my Blackness would ultimately connect me to my true home, but I was naïve. That was my fault because, like so many children of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, I romanticized Africa. I had absorbed a single story — this idea that touching down in Africa would unlock something instant and spiritual in me. But TikTok carousels show only one side of a Black Westerner’s journey back to Africa.

Some people may see this essay as their single story of the return to Africa, and, more specifically, to Ghana, as problematic. That wasn’t my experience. I was grateful to walk on the land where my ancestors walked and to see what they saw.

I enjoyed learning about the people, history, and culture of Ghana. The long bus rides from Koforidua to Winneba to Kumasi and back again turned strangers into friends as we talked, laughed, and shared snacks for hours. I met local Ghanaians who made my trip unforgettable, like the local seamstresses who welcomed us into their shops with laughter and warmth, the children who were excited to meet us, and the guides and locals who patiently explained the country’s rich culture and traditions.

Following my ancestry to Ghana was a learning opportunity in so many ways, including realizing that Africa isn’t the solution to my yearning for home.

Maybe no one place is.

This journey to Ghana taught me that home and connection don’t magically emerge from a plane ticket or a DNA match. Home is built through relationships, memories, and connections.

Maybe my home is Canada and Barbados and my connection to Africa. It’s something I carry with me in my DNA, shaped by every place my ancestors touched.

I may never know my tribe by name, but I’m rooting myself in the communities I choose and the ones that choose me.

By

By