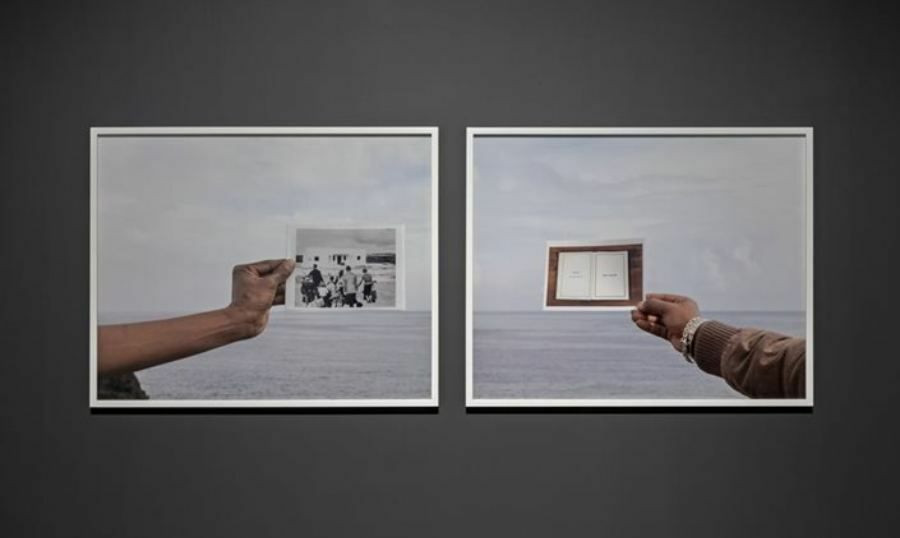

A description of his work says, "Petros’s art reflects his research into the complex layers of colonial and postcolonial histories connecting East Africa and Europe. Employing archival materials collected over a period of seven years, documents that attest to the Italian presence in Ethiopia and Eritrea between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Petros has developed an expansive suite of works that reflect on the lingering effects of colonial memory. Composed of a multimedia installation of serigraphs, photographs, sculptural works, a film and soundscape, the works highlight the ties between the contemporary resurgence of nationalism and a suppressed colonial past."

As a young refugee who entered Canada with his family after fleeing war in Eritrea, he’s maybe not the first person you could have assumed would become an international artist with a borderless world view. However, that upbringing, paired with a naturally creative impulse, likely shaped that unique perspective he draws on to reflect on the issues that inform his work. I spoke to him for Byblacks about his lived experience, how the untold stories of our past inform our present and future, and the dangers of being defined by a flag versus being a global citizen.

What sparked your interest in pursuing a career in art?

I was passionate about art from a young age. There was an art teacher in high school who understood there were experiences specific to me that I could engage with through art. Photography, film, and music were things of interest, but I simply had no sense that art was something I could do for a living. I thought of it as a hobby one could entertain while doing something more practical like being a lawyer. There were no models for me of how someone with my experience or position within Canada could even remotely entertain a position within the arts. Art was a mirror in which I was trying to see myself, which was an image that simply wasn’t out there at that time. One particular moment I can remember distinctly was when I was travelling in Central America with a German documentary photographer. He was taking photographs that were going to be part of photo essays for various German publications, which was really the first time I realized people could make a living doing art. He wasn’t even necessarily doing what I wanted to do, but it was at that point having a career in art became a possibility.

The English translation of your exhibition “Spazio Disponibile” is “Available Space”... what is the available space you’re referring to?

In a literal sense, I’m referring to the vacant ad section that appeared in an Italian periodic publication that ran from 1906 to 1943, which was almost the duration of Italy’s colonial project, called Rivista Coloniale. That’s what I’m referring to in a physical sense. From the artistic perspective, the space represents the historical gaps in memory, culture, and untold stories that have yet to be acknowledged or recognized. I’m always trying to find the metaphor that can transform a physical thing into a philosophical or conceptual proposition. When we talk about available space, we know the Italians meant Africa was an empty space to be exploited, where the people there were not considered as being present. It’s the same sort of thinking colonizers had about Canada. When I say available space, I’m looking backward in history in order to find the available alternatives and potential stories that were not given the opportunity to materialize. If I can’t find these gaps in history, it means I can’t find them in the present or future. In this way, what I’m doing becomes a historical interrogation of the now.

Whether you’re talking about Mexicans at the U.S southern border, or Syrians trying to enter Turkey or Greece, it seems like there’s less available space for migrants today. Why do you think that is, and how would you relate that to what you’re trying to say with your work?

Events of border closures and xenophobic racist policies ensure this kind of fear. To be nomadic is the story of the human species. This is where we are now. What Europe is having a difficult time recognizing is that the places they went to are now coming back to them. The omission of their own historical intrusion into other spaces has become a much larger part of the mobility story. I’m looking at this from the vantage point of someone who is Eritrean, with an affiliation to Italy, but also within the context of Canada. The largest movement of populations in modern times from one part of the world to the other is Italians. So the bitter irony of Italy now implementing policies to neutralize the movements of populations based on xenophobia and racism, brings to the surface their own historical imperial formation; one which is almost entirely forgotten. Italians may say they had a short-lived empire, but to those living under that empire, it was anything but. Therefore, what I’m looking at is how the effects of Italy’s empire continue to resonate across time. Modern-day policies that result in the dislocation, dispersion, and displacement of people, are messy events rooted to things that have happened in the past. Part of the reason the Italian government initiated colonialism in North Africa, was to try and stem the tide of Italians who were fleeing to North America in droves in an attempt to leave behind poverty and instability in Italy. They were trying to get them to go to Africa. So this specific triangulation in my work is showing that these are connected histories.

As an artist who came from Eritrea, studied in North America, and now lives between the U.S. and Canada but exhibits around the world, do you consider yourself someone bound by a flag per se, or more as a global citizen?

I abhor nationalism. My politics are aligned with the notion of no borders. This is what I fundamentally believe in. I’m as critical of nationalism and the way it may unfold in Eritrea, as I am of how it may unfold in Canada or anywhere else in the world. I recognize the privileged position from which I can say this to you. I’m more interested in a form of belonging that is international. The perceptive I have is aligned with the idea I can move and work from place to place, but I recognize my passport allows me to be able to do that. There’s a tension between the fact that I know my family was forced to flee the circumstances of war, but now I move around by choice while getting to address both forced mobility against mobility by choice.

Dawit L Petros: Spazio Disponibile (Available Space)

The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery

231 Queens Quay West, Toronto ON

January 25 - May 10

Byron Armstrong is a writer living in Toronto who has been published online and in print, for both local and national publications. He writes essays, short stories, opinion pieces, and in-depth interviews, within the sphere of politics, art, design, business, and travel. His general musings can be found on Twitter as @ByronArmstrong6.

By

By