Gary describes the transition from London to New York City as “No big deal.” He says, “Although a different country, the hustle and bustle, smells, and the attitude of inner-city living was very familiar to me. My neighbourhoods still felt the same. NYC was predominantly Spanish (Puerto Rican), whereas London was predominantly white. Navigating both places was exciting, dangerous and stimulating to a young black man.”

However, Gary describes Fredericton, N.B., as “entirely different” though it stimulated him in ways he “couldn’t foresee.” He bought his first Canadian home in 2008, two months after arriving and had to learn how to adjust to the lack of hustle and bustle the area outside New Brunswick’s capital had to offer. Gary was used to having transportation at his door in London and never needing a car, juxtaposed with the ruralness he experienced in New Maryland. “In Fredericton, one starts to walk through life at a different cadence to the rhythms of London and NYC, so my transition went. Forcing me to slow down is a by-product of living in Fredericton. I am no longer part of the rat race, and what I photograph has changed because of it. There were times that I felt I’ve been sent here to learn patience, which is never more noticeable than in the harsh N.B. winters.”

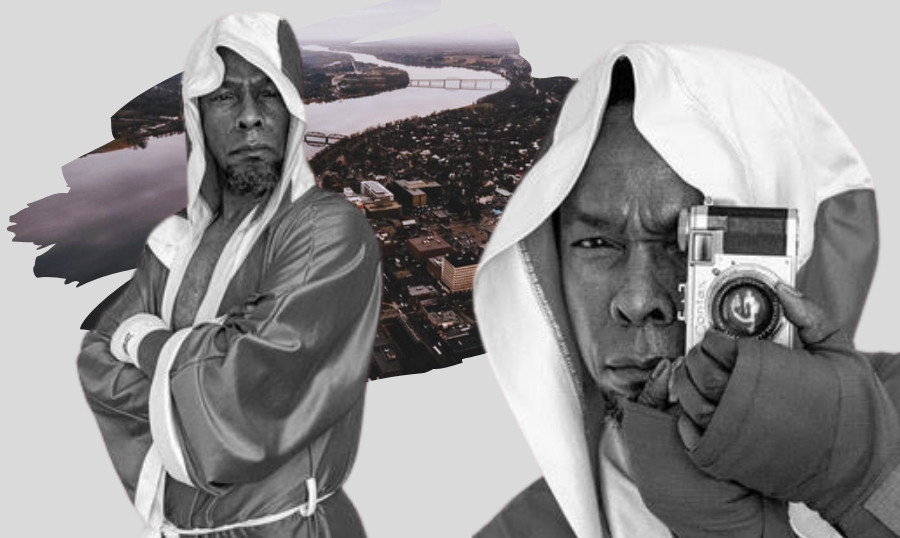

After fourteen years of calling Fredericton home, Gary will be the first Black person to have a solo exhibition at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery. As diversity rises in New Brunswick, more and more People of Colour are becoming the first of their race to be awarded or included in something. Coming from such diverse cities and knowing New Brunswick’s history, Gary had to wonder how this came to be.

“Since finding out that I am to be ‘the first Black’ to have a solo exhibition at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, my first thought was ‘Why am I the first?’ There have been Blacks in New Brunswick for over 300 years. There were artistic/creative Blacks here from day one. But, as a whole, Canada has not valued the artistic contributions of their Black citizenry, and N.B. followed suit. The only N.B. artist that I know of is Edward Mitchell Bannister, who had to leave N.B. and gain fame in the U.S., just to be accepted once again in the embrace of N.B. Art is important to me as an individual. Art helps me to explore, to see the world without limitation or restriction, and above all, to dream. Depriving those who came before me of the venues in which to show others their dreams; intentionally creating 'prisons of the mind' to enslave and pacify the populace. So, to sense that this was withheld from all who have preceded me has made this exhibition even more significant.”

He continues, “It has taken the Beaverbrook Art Gallery 62 years and although the number of Blacks in N.B. has increased, I’ve had to travel from London to NYC, back to London and finally to Fredericton—just to represent.” Gary hopes that being the first Black artist the Beaverbrook Art Gallery features, challenges how art is accepted, shared, and perceived in New Brunswick. “Being the ‘first Black artist’—in my view—now challenges the perceived corridors of acceptability for art in N.B. My exhibition will provoke discussion and debate and will violate and validate individuals in equal measure. The years of studying, learning, and teaching others my craft on different Continents; practising in areas not commonly associated with People of Colour, this exhibition has been my ultimate blessing to date. We all learn from those who have gone before us, and all I have learned has brought me to where I am today.”

Gary recognizes that this exceptional distinction means many artists before him were not given the accolades they most likely deserved. “I still shouldn’t be the bearer of such an appellation in 2022. With the Beaverbrook Art gallery being 62 years old and with all the significant strides Black people have made in the last 62 years prior, for this to be associated with me—for evermore—is a blessing that I hope will inspire others to be the ‘first something’ in their futures. But my being the first Black soloist in a provincial art gallery would not be a thing if N.B. art was truly open to all. For me, to still find colour barriers/markers that are still up, which I now must knock down is alarming, but by doing so, I make the concept of solo exhibitions by a Black artist at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery no longer a ‘first.’ The door is now open. I wish to thank Nadia Khoury, my representative at Gallery on Queen and to John Leroux at the Beaverbrook for taking the leap of faith and looking at photography as a credible art form (for art galleries) and for understanding it to be another medium for those of us with the desire to converse with imagery.”

Gary notes that his exhibition is about “differences,” more precisely the similarities of differences between boxers in North America. It also speaks about the similarities of differences that exist in his and Larry Fink’s photography worlds. “Larry Fink and I are from completely different backgrounds, but the sport of boxing has allowed us to connect; spiritually and esoterically. The medium that we both use to connect with the world allows us the privilege of entering a realm that few outsiders rarely have the chance to see. Our contradiction is that Larry Fink is a white male photographing Black boxers and me, Gary Weekes, a Black male photographing white boxers. Both of us sticking out like a sore thumb in our respective arenas, but both being accepted as documentarians revelling in the beautiful ferocity of ‘the Sweet Science.’”

Gary adds that “The exhibit pits us as photographers in the same light as the pugilists when ‘squared-off’ and ‘staring-down’ one another at the weigh-in or just before the fight. Larry in this case is the ‘old pro,’ the holder of all the accolades, with a list of accomplishments (wins) as long as his arm. Me, on the other hand, an ‘up and coming’ photographer—hungry—hoping to take Larry’s title. To win, we show the skills that have been honed for decades, with our fight venue being the Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Thus, pushing documentary style photography just a little further, for the benefit of our craft and our artistic oeuvres. There will be no knockouts or ‘points win,’ just the acknowledgment that we’ll put on a brilliant show that will cause people to learn more about each artist and to witness history in the making.”

Gary is no stranger to boxing and has enjoyed the sport for years. “I always enjoyed the sport of boxing long before I picked up a camera. My only foray into the sport was as an 11-year-old in a boxing club situated in my junior school gym in London, England. This was where I learned about the science and brutality of the fight game and where I quickly learned that I didn’t have the heart necessary to be a boxer. I decided then that I would love the sport from a safe distance outside of the ring. Fast forward to me in my late twenties with my cousins and friends, 4 am in the morning waiting to watch Mike Tyson on pay-per-view in my cousin’s bedroom in London. We’ve been up since midnight watching all the preliminary bouts while eagerly waiting for Tyson’s world title charge to commence. At 4:03 am the fight would be over with a spectacular flurry of accurate punching by Tyson and the look of utter annihilation on his opponent’s face. Although frustrated and amazed in equal measure, I knew I’d be back for the next 4 am three-minute fight in the future!”

Gary discovered photographer Larry Fink while revisiting NYC, “I saw Larry Fink’s Boxing Monograph on one of my trips back to NYC to visit my family. Whenever I visit NYC I tend to visit photography bookstores and boxing was my first encounter with Larry’s work.

I was immediately amazed at how I saw elements in the style of Larry’s images which I felt was very similar to what I was shooting at the time. I loved that his depiction of boxers was beguiling, totally devoid of the artifice shown in the magazine Sports Illustrated. I was intrigued by the warts and all quality of these images and the beauty imbued therein. Larry’s images connected with me on a technical level because it reflected how I ‘saw’ the world at that time. My own images were shot with a wide-angle lens and apart from using flash, dealt with people just ‘doing their thang.’ When I got the opportunity to shoot at Fredericton Boxing Club (thanks to my coach and neighbour David Furneaux), I knew that I wanted a decidedly pared-back look to my imagery—reminiscent of Larry’s, but with more of ‘me’ and how I saw boxing, rather than it being just a homage to Larry Fink’s Boxing Monograph.”

While living in Fredericton, Gary has made increasing the visibility of Black artists a priority on his agenda. “My involvement as a Board Member of the Fredericton Artists Alliance (FAA) and the New Brunswick Black Artists Alliance (NBBAA) has made the participation of Black storytellers incredibly important. When Kodak brought out the Box Brownie, it was said that ‘Photography was now available to the masses.’ I don’t believe this statement to be true for my Black ancestors. The cost of the cameras and processing was still out of the reach of many Blacks of the day and consequently, we lack a lot of true day-to-day documentation of how our communities existed at this time. Digital cameras and camera phone technology have levelled the playing field, and now we see stories from the Black diaspora that were never visible before. Visibility brings a sense of belonging, pride in ourselves, and our communities. We now feel that everything is possible because we see and show the love that our people have always had for one another—not clouded or misconstrued by the media. Our history has been an oral one, passed down from generation to generation, with our elders tasked with doing so. This will continue…, but alongside our verbal history will sit our visual history and Black achievements both big and small will be documented by those with cameras and phones to make an archive that is true to us as a people and not misinterpreted or misrepresented by the gatekeepers of negative media, who have penned and described Black people as ‘less than’ for far too long.

Change has always been slow, but the power in digital photography and the ability of those who participate therein, will challenge the status quo and will effect change more rapidly than ever before.”

By

By