Const. Michael Thompson, 37, was found in medical distress at his home in Durham Region on April 10, police say. He was rushed to hospital, where he died three days later.

Toronto police released a statement about the officer's death Thursday — more than seven months after it happened.

Meaghan Gray, a spokesperson for Toronto police, said Durham Regional Police started a sudden death investigation back in April. The results of that investigation came back in July, concluding Thompson died of a fentanyl overdose. In a written statement Thursday, police said the quantity of fentanyl in his system was too large to have been caused by casual contact with the drug.

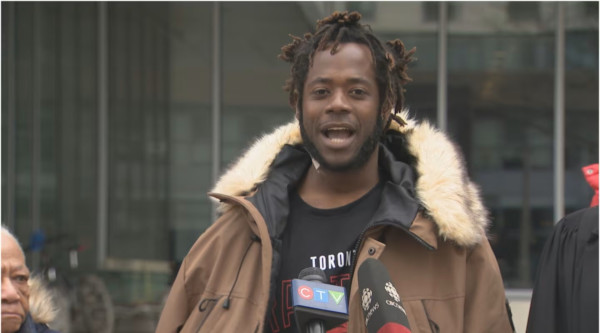

"This is something in the public interest," said Leigh Chapman, a registered nurse and harm reduction advocate. "We should have known about it in July."

Chapman is angry police did not make Thompson's cause of death public earlier. She's a volunteer at a supervised injection site in Toronto's Moss Park and lost her brother Brad to a suspected fentanyl overdose.

"[Thompson] overdosed in April, they found out the results of the [toxicology] screen in July and it's not reported until November?" Chapman pointed to a spate of drug overdoses in July, which resulted in harm reduction workers opening the unregulated safe-injection site at Moss Park.

Other overdose deaths were reported immediately, and Chapman said Thompson's death should have been no different. Police said, however, the information was withheld for investigative reasons.

"For the service as a whole, and members of the public, we wanted to wait until we had as much information as we could before we released that information today," said Gray.

Police investigation ongoing

"It is always a difficult time when we lose a member of the Toronto Police Service, regardless of the circumstances," the police statement reads. "It's even more difficult when the circumstances of a specific loss leave us with more questions than answers." Gray said the investigation into Thompson's death is an effort to answer some of those questions.

"We had to take a look at a review into his professional responsibilities as a drug squad officer, we wanted to take a look at any personal wellness issues that he had, and we wanted to broaden that review to include, for instance, a review of the protocol when it comes to handling exhibits at the drug squad." Police said the constable's death is an isolated incident.

"We don't have addiction issues at the drug squad," Gray said. "This was one officer who had taken drugs that included fentanyl, and he did overdose on those."

The statement said the constable was a good police officer who was respected by his colleagues, and that he had regular access to street-level drugs. The investigation into where Thompson acquired the drugs is ongoing. Gray said it's unclear whether or not he bought the drugs at street-level or got them from police exhibits. Still, she maintained protocols within the drug squad are strict.

"We've made some changes to some of the procedures and policies at the drug squad, but those were already very strict protocols," she said. "We don't believe this was an ongoing situation. We haven't determined, for instance, drugs were taken over a considerable length of time."

"Where he got the drugs from is not an answer we have. We may never know."

Disclosed death to attorneys

Gray said because of Thompson's role on the drug squad, Toronto police have disclosed his death to Crown attorneys who are working on cases the constable was involved in. Some of those cases come forward as early as next week.

"There will be some consequences in the justice system when it comes to cases he was involved in," Gray said. "That's just the inevitable outcome when something like this happens."

Thompson was hired by Toronto police in 2006. He was assigned to the drug squad in 2014. In the statement, police offered their condolences to his colleagues, family and friends. He was single and did not have any children.

"Everybody is devastated," said Mike McCormack, president of the Toronto Police Association (TPA). "We were devastated when we had to bury him in April. Too young, too early. It's a tragedy."

McCormack said officers on high-risk squads, like the drug squad, are monitored more closely than uniformed officers. They also meet with a psychiatrist annually to assess their well-being.

"It was a tragedy when we lost Mike," McCormack said. "He was a great officer, a very dedicated police officer, and it's really a very tragic circumstance to lose an officer."

Police said there are resources in place within the service to help its members deal with personal crises, health problems and other issues, like PTSD. Members of the service have also been asked to let managers know if there are gaps in services.

With files from Sebastien St-Francois and John Lancaster

By

By