In the case of his upcoming exhibition, A World Discovered Under Other Skies, at The Power Plant Gallery, he does it through his own cultural lens as a Haitian-Canadian artist. Mathieu has a sense of purpose that includes a responsibility for the next generation. As the first Haitian-Canadian artist with work bought by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, he used his visibility (and money), to keep the doors open for other underrepresented artists behind him. Mathieu intertwines his activism with his practice, much like how his work examines our intertwined existence in this world. Among other topics, I spoke to Manuel Mathieu about his journey as an artist, the realities of working within a structure while trying to build your own, and why he is ready for words like “struggle” and “resilience” to become past tense descriptors for Black lives.

When did you begin on this journey to become an artist, and when did it become a viable option in terms of being a career?

It all started about 15 years ago through my mentor, Mario Benjamin, a self taught Haitian artist who is my father’s cousin. It was a liberating experience. I was a rambunctious kid, but discovering a creative soul with that kind of purpose was revelatory. I immediately understood it as something I really wanted to do. As far as viability goes, it’s sort of a trick question because it’s never really definitive. I’m doing okay and putting money aside, but I’m not in an industry like engineering or medicine that civilization will always need in order to survive, and I’m always cognizant of that. I would say it became viable to me personally after I obtained my Master’s degree, around 2017 (Tiwani Contemporary, London UK), which is when I started showing with international galleries. That’s when I started making enough money that I could sustain my career.

It’s interesting because when you think of artists you don’t think of them as people who are necessarily thinking about money. There’s always that story of the struggling artist for instance.

It’s the Van Gogh comparison; artists are supposed to be half crazy and die penniless. I just did an interview where I discussed what I would do as the Minister of Culture to promote arts and culture. In Quebec, there are companies like Bombardier that have government support programs created for them to help secure their assets. Artists are also entrepreneurs who need programs to secure our autonomy. For some reason, it’s really ingrained in society that artists are part of the recipe, but not necessarily the main ingredient.

Do you think there’s an intentional undervaluing of artists? If so, why?

I think it’s economic. In Haiti, there’s a legacy of artists not being able to sustain themselves, so it’s hard for parents to see it as something to have success in. Even here in Quebec, it’s the public sector who finances art projects because there isn’t enough money coming from the public. If I was the Minister of Culture, I would recognize the need to get the public, specifically the next generation, accustomed to the idea of spending money on art. In certain European nations, you get a 100% tax return on any investment in art and culture. I proposed a tax credit of 20 or 35% on anything invested in art and culture, like an art piece or stage play. If you launch a real campaign to inform people they can have those kinds of tax credits through investing in art, you will create a boom in the local art economy. My other thought was the dissemination of a cultural passport, with the idea being that every year from 18 up to 25 years old, you would receive a stipend of $1000 to spend on culture. This would cultivate a mentality of sustaining culture and a curiosity about what art actually is. There are ways that wealthy nations can foster and sustain interest in the arts if they want to.

Can you explain how the theme behind the title “A World Discovered Under Other Skies?” relates to your upcoming exhibition?

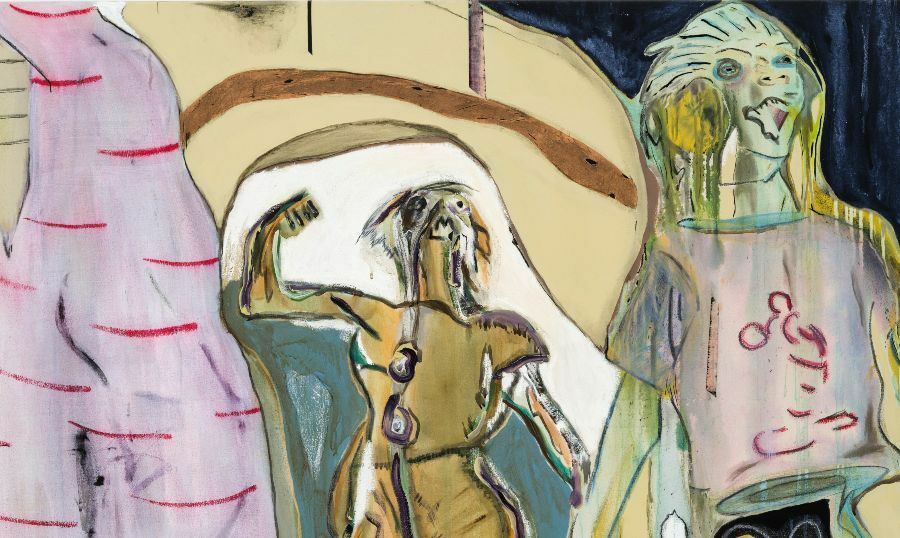

One of the curators of the exhibition actually titled it. It’s borrowed from something he read in political philosopher “Frants Fanon’s” book “Les Damnes de la Terre” (eng. The Wretched of the Earth). We integrated the idea of sky, as all the walls will be blue to create an immersive experience with paintings, drawing and ceramics. The relationship between the title and the work can go in several directions. I could talk about how specific works connect to my culture or examine what it is to be Black but not African-American, because a lot of what is understood about Blackness is related to African Americans.

Recently, the art world has been taken to task over its marginalization of Black artists and art workers...As a Black artist, with so much of your work looking at a country with a well documented struggle against colonialism, where do you see the need for a decolonization of the art world and how do you envision that happening?

I think it’s important for artists to understand we’re working within a bubble, and in order to truly examine that question you have to see things from outside the bubble, or the structures that are defining what is art today. It’s kind of difficult to do without reimaging the world. Unlike White artists, I’m not just doing art. I’m also an activist because I’m preserving my culture through my imagination. For instance, after the Museum of Fine Arts (Musee des Beaux Arts) bought my work, I became the first Black Canadian-Haitian artist to be shown at the museum, which I thought was unfortunate. So I initiated the Marie-Solange Apollon fund, named after my grandmother, for the Museum to buy the work of underrepresented artists. A White artist isn’t really obligated to think about things like that, because there are a number of people in their world who are just funding a bunch of different things for them. I started the fund with $25,000, which is money I didn’t put into funding my own career. I look at it as a kind of invisible tax I pay for having these values. I’ve also launched a film production company that helps mainly Black artists. That’s sort of my way to create visibility for my kind. Considering the machine we’re talking about, it’s very little, but it’s important because the small gestures may lead to the next Ava DuVernay in the next decade or so.

As an artist of the Haitian diaspora, when did you first come to this idea that Haiti’s story could sort of represent a microcosm of the world?

When we look at the Haitian revolution, there was a momentum that got us together, but today, it’s almost impossible to get us together because of the economic, geopolitical, and racial factors messing things up. That microcosm is suffering right now for many reasons. Haiti is a good place to understand the success of “empire”, which succeeded in breaking the country in every way possible. I have to say, in terms of Haiti, there’s still a beautiful context in that we’ve kept a level of dignity, self respect, and openness to the world, all throughout. We’re good people just trying to live, while overcoming problems orchestrated by invisible hands. There's dignity in our capacity to survive and preserve our culture at all costs.

There’s a sense of resilience through struggle.

I don’t want to use words like “resilience” and “struggle” to describe my work or culture. I want to use words that talk about where we go from there. I think resilience and struggle are launching places from where we can make big leaps as dreamers, artists and authentic souls. That word resilience is a trap, because we can get used to carrying around all this unnecessary weight that others have placed on us, as opposed to looking at why we’re having to bend under this weight in the first place. I try to bring these different perspectives, a space of ambiguity, into my work. When you see it, you’ll find that it caresses you on one side, and slaps you with the other.

Manuel Mathieu: A World Discovered Under Other Skies

The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery

231 Queens Quay West, Toronto ON

*September 26th 2020 to January 3rd 2021

Byron Armstrong is a writer living in Toronto, Canada who has been published online and in print, for both local and national publications. He writes short and long-form essays, reviews, in-depth profiles, and interviews. His writing focuses on the intersection between art, society, and politics. A link to all his published work can be found on his website: byron-armstrong.com.

By

By