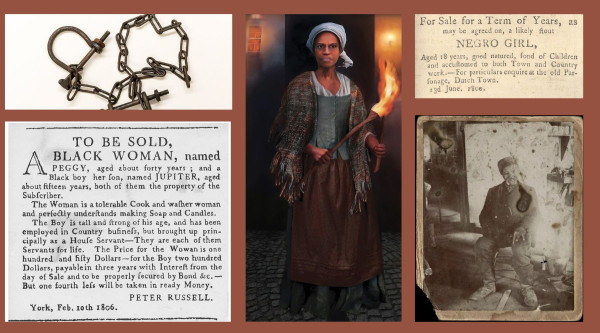

The son of freedom-seekers from Kentucky, Elijah was born on March 2,1844, in Colchester, Canada West (Ontario). His parents were George and Millie McCoy. Although born a slave, George had been freed by his white father, Henry McCoy, a tobacco grower and cigar manufacturer, at the age of 21. However, Millie was enslaved to the Gains family and thus any children the McCoys might have were destined, under American law, to be enslaved as well.

They fled to Canada in about 1837 with the help of the Underground Railroad. Like a great many African American refugees in Canada, George volunteered to help defend the province when the Mackenzie Rebellion broke out later that year. As a reward for his military service, George McCoy received 50 acres of land in Lot #11, on Snake Lane, Colchester South Township on which he constructed a single-story log cabin. He and his wife would eventually become the parents of twelve children, at least five of whom attended the Harrow Public School.

Elijah would become one of the greatest inventors of African descent in either Canada or the United States. During his lifetime he would patent more than 57 devices, and was internationally famous as a brilliant inventor. The McCoy family took a great risk; they began making preparations to return to the United States in 1846. According to some sources, this happened when little Elijah was only three years old.

Despite the danger that Millie and their children might be captured and re-enslaved, they did choose to cross over the Detroit River into Michigan. Their motive was most likely to improve the educational and future employment opportunities for their children. The McCoys settled in Ypsilanti, Michigan, although they apparently retained ownership of their Colchester farm for some years. Their new home was a cabin on the farm of the Starkweather family, who hired a great many workers to help harvest the fruits of their large orchards.

Once George established in his new home, he began growing and harvesting tobacco to use in the manufacture of cigars, his craft in which he had been trained in boyhood by his white father. The Starkweathers along with a number of their Washtenaw County neighbours were also engaged in the Underground Railroad operations, and the McCoys took an active part, according to an interview conducted in later years with Ann McCoy, the fourth child of George and Millie. She stated that once her father began growing and processing tobacco again, the family wagon was fitted with a false bottom. This was used to hide freedom-seekers on their way to Detroit river ports from which they could be transported across into Canada. As a boy, Elijah displayed remarkable mathematical and mechanical aptitude. His parents resolved to save enough money to send him to an engineering school that would accept a youth of African descent. He left for Edinburgh, Scotland, at the age of 16, and excelled at his studies. He returned to his Michigan home a qualified master mechanic and engineer.

The Civil War ended in 1865. The passage of the 13th Amendment to the American constitution freed all the slaves in the United States. Now secure from enslavement along with all his brothers and sisters, Elijah sought employment as an engineer. However he was forced, because of racist hiring practices at the Michigan Central Railroad, to accept a job far beneath his qualifications. Elijah began working as a fireman and oiler on the railroad. This required him to shovel two metric tons of coal into the firebox of the steam engine every hour. Furthermore, every time the train stopped to take on water, he had to walk along the tracks carrying an oil can so he could lubricate the moving parts of the heavy iron steam train. The working parts and particularly the axles of steam trains were very vulnerable to overheating, which could cause the warping of the metal or the outbreak of fires.

Elijah McCoy patented his first major invention in July1872 to help solve this problem. This was a lubricating cup that dripped oil into the moving parts of the steam engine and undercarriage, meaning that the mechanical parts were continually oiled while the train was in motion and there was no further need for manual oiling. The improvement of his lubricating cup in his home workshop resulted in a second patent one month later. The Michigan Central Railroad enthusiastically adopted the new invention, although some other companies were less willing to buy into an innovation conceived and developed by a person of African descent.The McCoy lubricating cup would revolutionizet he transportation industry, as would the progressively more sophisticated inventions patented by Elijah McCoy over the years.While other companies copied his design, the McCoy lubricating device was so unique and reliable that it is believed the term “the real McCoy” came into usage to distinguish Elijah’s invention from those of imitators.

Although he continued to patent his devices in both Canada and the United States, McCoy never returned to Canada to live. Elijah moved to Detroit with his wife, Mary E. McCoy in 1882, when he left the Michigan Central Railroad to focus his attention on inventing. On January 9, 1883, he patented an improved lubricating device, US patent number 270,238. At this point in his career he also consulted for the Detroit Lubricating Company. In association with the company’s manager, C.B. Hodges, he designed a new steam dome for locomotives patented in 1885, as well as another lubricating device patented on December 24, 1889, under patent number418,139. Newspapers of the 1880s commented on his more than 28 patents, under the achievements of “Our Colored Citizens,” in the Sunday Leaderof Wilke-Barre, Pennsylvania published March 11, 1888.

Elijah’smultiple patents over succeeding decades included a variety of new lubricating devices and other items relating to transportation. His inventions were adapted to many other uses, such as drilling for resource extraction, manufacturing, and for use in steam ships. He continued to invent well into old age, including an important breakthrough employing powdered graphite in lubrication for the airbrakes that were used in the much larger locomotives of the late 19th and early 20thcentury. He was 77 at the time.

His brilliance was widely recognized during this lifetime, with newspaper articles citing his inventions published across the United States and beyond.

Among many other honours, the Bethel AME Church in Detroit mounted an exhibition of his mechanical drawings accompanied by a banquet, musical performances, and lectures by local dignitaries, as mentioned in the Detroit Free Press of December 15, 1901. However, Elijah was never financially able to invest enough money to manufacture his own products, so he sold his patents outright to companies that went on to make millions from his creativity and design expertise.

In later years, he decided to sell shares in his more recent patents to finance his own workshop and independent manufacturing company. It was not until he was quite elderly that he was able to establish the Elijah McCoy Manufacturing Company, which he did in Detroit at age 77 in 1920.

Elijah McCoy married twice. His first wife was Ann Elizabeth Stewart whom he married in 1868, but she lived but a short 4 years. He married again in 1873, to Mary Eleanor Delaney. Known as the “Mother of Clubs,” Mary became a community activist and philanthropist of considerable note. One of her accomplishments was as a founding member of the Twentieth Century Club, a group of leading ladies of African American Detroit. They lent their voices to multiple worthy causes, including demands for a new school bill to improve public education, as reported in the Detroit Free Press of February 17, 1899. With the support of Elijah’s invention income, another of Mary McCoy’s accomplishments was the establishment of the Phyllis Wheatley Club, which she represented at the National Association of Colored Women’s convention in Detroit held in August, 1899. The organization, first established in Nashville, had a Detroit chapter by1897. Its purpose was to serve the community through moral and educational uplift, provide assistance in housing for Black women in urban settings, and to support both the aged and young girls.

She also helped established the Michigan State Association of Colored Women, and represented the organization at state and national meetings. Mary E. McCoy was an ardent supporter of suffrage for Black women, and president of the Lydian Association of Detroit, which was a self-insurance organization to provide sick benefits and burial funds for Black women in difficult circumstances. As founding President of the Sojourner Truth Memorial Association of Michigan, she helped raise funds in honour of Sojourner Truth to provide African American children of formerly enslaved parents with scholarships to attend the University of Michigan. With Detroit’s first African American schoolteacher, the Toronto-educated Fanny Richards, in 1898, Mrs. McCoy was co-founder and first vice-president of the Phyllis Wheatley Home for Aged Colorored Ladies. Both the Phyllis Wheatley Club and the home for the elderly had as their namesake the first published African American poet, and both served the Detroit Black community for many years.

She also helped found the McCoy Home for Colored Children. This was both ano rphanage and a daycare centre for the children of women engaged in domestic service. ElijahMcCoy, too, was engaged in community activities. He was the first to introduce Booker T. Washington to a Detroit audience, and the Detroit Free Pressof March 3, 1895, noted he had been selected to give an address at the memorial to be held at Detroit’s Bethel Church in honour of the late Frederick Douglass on the following Tuesday. In June, 1906, he and a number of leading citizens of African American Detroit founded “The Business Men’s Council,” of which Elijah McCoy was named the second vice-president. The organization was intended to “establish cordial relations between themselves and the white people of the city, and to take steps to instruct those colored brothers who have not lived here long, in the history of the lives of the earlier residents.”

Tragically, after nearly a half-century of marriage, Mary passed away as the result of a terrible car accident in which Elijah was also injured. This took place in 1922, and Mary died in 1923. Elijah traveled widely over the course of his life to disseminate information about his inventions and to conduct sales to various corporations. For instance the Appeal newspaper of St. Paul, Minnesota, noted on May 9, 1903, that he was in town to “close a large deal with a major railroad corporation.” At 80 Elijah McCoy patented a tire he had designed. He also invented a variety of non-transportation related items, some of which he also patented. One was a folding ironing board that was designed to serve the needs of his wife, Mary, and another was the lawn sprinkler.

The Star Press of Muncien, Indiana, of June 15, 1924 reported that by that year the US government had granted 57 patents to “Elijah McCoy, a negro.”For a time, Canadian Pacific Rail paid him substantial royalties for the use of his various intentions. However, despite his and his wife’s generous philanthropic efforts, and having patented nearly 60 devices over the course of his long career, Elijah still found himself without sufficient means in his later years. Sadly, he passed away in the Poor House at Eloise Michigan, in 1929. Although he had once been very comfortable financially, and his income had enabled his wife Mary to support multiple worthy causes throughout her lifetime, Elijah McCoy never reaped the full rewards he was due for his many inventions. However his brilliance is recognized in many ways, including the fact that the first US Patent and Trademark Office established outside of Washington DC –the one in Elijah’s adopted hometown of Detroit –was named after him by the United States Senate in 2011. Mary, too, is remembered. According to the press release dated November 9, 2016: “On July 29, 2016, legislation introduced in the House of Representatives by Congresswoman Brenda Lawrence, Michigan’s 14th District, was signed into law by President Obama to rename the Post Office building located at 10721 E. Jefferson Ave, Detroit, MI as the ‘Mary E. McCoy Post Office Building.

This essay was written by Karolyn Smardz Frost, Ph.D and originally published on the Rella Brathwaite Black History Foundation website.

By The Rella Brathwaite Black History Foundation

By The Rella Brathwaite Black History Foundation