Photographer: Zun Lee www.zunlee.com

IG, Facebook: zunleephoto

Twitter: @zunleephoto

Project Timeframe: Sep 2011 – present

Publisher/Contact/Pre-order: Ceibafoto LLC

Book Release: September 19, 2014.

Awards: Named on “PDN 30 2014,” Photo District News’ annual global list of 30 new and emerging photographers to watch.

Book Trailer: Father Figure – Exploring Alternate Notions of Black Fatherhood

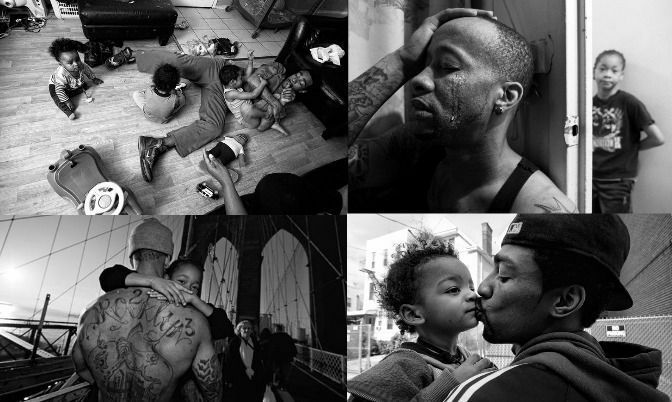

Over the course of three years, photographer Zun Lee built trusted relationships with Black fathers from different walks of life. He witnessed intimate parenting scenarios that are often missing from the public realm and that he himself did not experience as a child. Deeply autobiographical, the book of photographs titled Father Figure – Exploring Alternate Notions of Black Fatherhood connotes Mr. Lee’s attempt to deal with his own resentment toward his absent Black father.

Reportage photography has been one of our most valuable resources when it comes to examining the human race from the 19th century through today. Throughout history many have been intrigued by the story behind a single photograph—a captured frame of hope, despair, conflict or exhilaration. The instinct of many professional and amateur photographers to snap that split second of humanity has been a gift to all who seek a glimpse of the past. There is a stillness and an indelible command of focus that leaves an observer transfixed when a documentary image is the epitome of the perfect shot. Self-taught photographer Zun Lee has been on a lifelong quest looking for that perfect image—that loving father.

Lee, a Toronto-based physician and now self-described street photographer, was born in Germany but knew as a boy that his personal story was incomplete. He discovered early on that his upbringing to a Korean mother and father was not his true background. The real story: Lee’s Black father left his mother upon learning she was pregnant. The disclosure of this truth left Lee with a sense of loss and abandonment that stayed with him as an adult. In a search for the compassion of which he felt robbed, Lee and his camera sought out images of strong, involved and devoted fathers—Black fathers—who society has deemed nonexistent.

Photographing the Black father has taken Lee from Toronto to cities in the United States such as New York and Chicago, IL. He notes the dire statistics provided by agencies, such as KIDS Count Data Center in the U.S., that almost two-thirds of Black children are raised in single-parent households, the vast majority of them being led by the mother. Says Lee, “Father absence is a highly visible social issue that affects all demographics but stereotypes of deadbeat Black fathers abound in mainstream media. Much of the imagery countering these stereotypes has remained formulaic, too, often consisting of ‘über-dad’ archetypes, (for example The Cosby Show’s Dr. Cliff Huxtable), celebrity fathers and ‘traditional’ family patriarchs.”

Lee’s photographs cover a range of economic realities including struggling families. But they are filled with humor, sincerity and the unmistakable bond that an “everyday” Black father can represent. “Scenes that can stand on their own and humanize the black experience without demanding perfection or respectability,” says Lee. “I was raised in an African American context for most of my life, and the experience I and many of my friends had of growing up surrounded by loving Black families – that experience simply didn’t add up to how society wants to portray Black men and Black fathers.”

Some of Lee’s most exciting moments during the shoots: The moments I spent living and working with the families were perhaps the most fulfilling for me because it wasn’t just about photography. It was about immersing myself in contexts that allowed me to revisit my childhood, reclaim some of my experiences and above all, get to a place of forgiveness for any resentment I harbored.

Lee’s biggest challenge: The biggest challenge was identifying, approaching and developing relationships with fathers and families that I wanted to work with. I spoke with hundreds of individuals, several dozen expressed interest, but in the end only a handful of families developed the kind of relationship with me that allowed me to get access to the inner sanctum of personal life.

Lee’s immersive approach to photo documentary: I think in this day and age of instant gratification, we very much have grown to appreciate the timeliness factor over anything else. Posting “Insta” now trumps richness of content. Even when it came to my project, people wondered why it took me three years and counting to “snap a few pics” of Black fathers. Many wondered why I want to get to know certain families and become part of their lives, rather than just inviting a number of fathers into a studio to take their portraits. I was really motivated to get “close” to the individuals, both physically and emotionally, because there are few examples of work like this out there when it comes to our own community, yet there are so many untold stories that need to be foregrounded.

What I mean by "immersive” really describes the entire process end-to-end: taking time to research the subject matter and at an angle from which I want to approach it, developing a firm point of view of what it is I want to depict, approaching and finding the right individuals to work with. All of this takes time and patience. Especially the last aspect – developing relationships with the right individuals - you cannot rush this. You have to gain enough trust that people will feel comfortable to not only have you around within their private spheres, but also be OK with you photographing them in situations where they are at their most vulnerable. In other words, you have to spend time with the families not as photographer but because of a genuine interest to become part of their lives, so you don’t end up being an intrusion. And of course, not every father I meet is willing to go there with me. I know I myself would have had a hard time inviting a photographer into my life like this, I’m way too guarded for that.

Audience reaction to the story: Many individuals reached out because they could relate to the personal story of fatherlessness, or because they could relate to the challenges of fatherhood and what it means to be a good father, irrespective of race or ethnic background. At the same time, there’s also been considerable backlash and confusion regarding why Black fatherhood stereotypes are a problem at all, why the special focus on only Black fathers, and people who simply refuse to believe that Black men can be capable, affectionate loving fathers, period. I appreciate both sides of the collective commentary because it exemplifies why these images and a broader conversation are needed.

A behind-the-scenes anecdote for our readers: I met with the editor of a well-known imprint when I was still looking for a publisher. The person really liked the work but told me that it needs to be “bolder.” The work was too “cute,” too “sensitive” and it needed that element of danger, aggression and titillation. My subjects needed to be more menacing, the scenes more testosterone. And I would get support in getting connected to the “right subjects” to make this happen. Needless to say, this meeting lasted for maybe five or so minutes before I thanked the person and walked away.

Thus, the integrity of the who is behind the lens truly does matter.

As of this writing, Lee has never met his biological father and says he does not have any details about him, including his name. “Would I want to meet him? Absolutely,” says Lee. “But I'm not on a personal quest to find him. That's not a pre-requisite for closure for me.”

Lee’s work has been published in Burn Magazine, New York Times’ Lens Blog, Revista Photo Magazine, Slate, and many other journals. In June, he was the only Canadian invitee at the prestigious LOOK3 LOOKbetween 2014 photo festival in Charlottesville, VA. Lee is a member of the documentary and photography film collective Aletheia Photos.