My talented friend Bill Greaves died August 25, 2014. He was 87. But he was really young at heart, relevant and a source of happiness for many people. He spoke to the crime of racism in the United States with powerful and moving documentaries about our excellence. Films like Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice, The First World Festival of Negro Arts, Voice of La Raza and the multi-episode series on famed statesman Ralph Bunche are just a partial list of Bill’s numerous contributions.

I am a proud member of the Black Documentary Collective (BDC) in New York City which is how I first met Bill and his wife and film partner Louise Greaves. I knew Bill was a pioneer with an impressive career. I did not know that he already traveled the same path I was on: actor turned director turned documentary filmmaker because of how much we cared about our culture—with a plan to master both fiction and non-fiction with true representation of all communities on screen.

Louise affirmed my assessment: “The only thing that meant something to him was the message he was getting across in his films. It was about his people, and the truth, and justice. He thought of his work as being in line with the evolution of the human race. He was very optimistic in that sense. If people knew the truth, they would be changed. They couldn't live with untruths after that.”

I found a kindred spirit in Bill. And in getting to know him and eventually working on his crew, I quickly became one of the luckiest young filmmakers learning from the best.

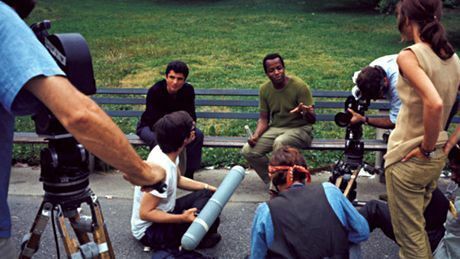

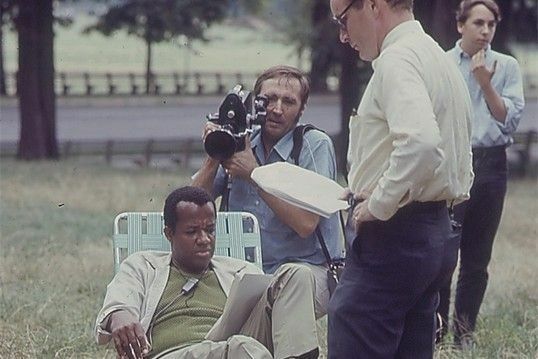

One late night in 2002 I had fallen asleep in front of the television and woken up to a crazy scene being played out on the tube. A very young Bill Greaves was being filmed by what seemed were behind-the-scene hidden cameras. Bill was shown running scenes with actors, then walking aimlessly through their Central Park set in New York, intercut with what appeared to be a mutiny from an exhausted crew. The crew comments were brazen and expressed their beliefs that working for this director was turning into one of the most bizarre and unsatisfying experiences they would live to see. I was shocked this was on television. And even more surprised a week later when I received a phone call.

Me: “Hello?”

Bill: “Nicole, Bill Greaves.”

Me: “Oh, hey, Bill! How are you?”

Bill: “Doing well. Nicole, did I hear that you own a PD150?” (The digital filmmaker’s signature tool at the time.)

Me: “Yes, I do!”

Bill: “Great! I’m wondering if you would be able to come film some scenes with me in Central Park. You see I did a film called Symbiopsychotaxiplasm about 35 years ago--”

Me: “Wait! You knew about that?”

Bill: “Knew about it. I planned it!”

Me: “Thank goodness.”

I was so relieved. We both laughed.

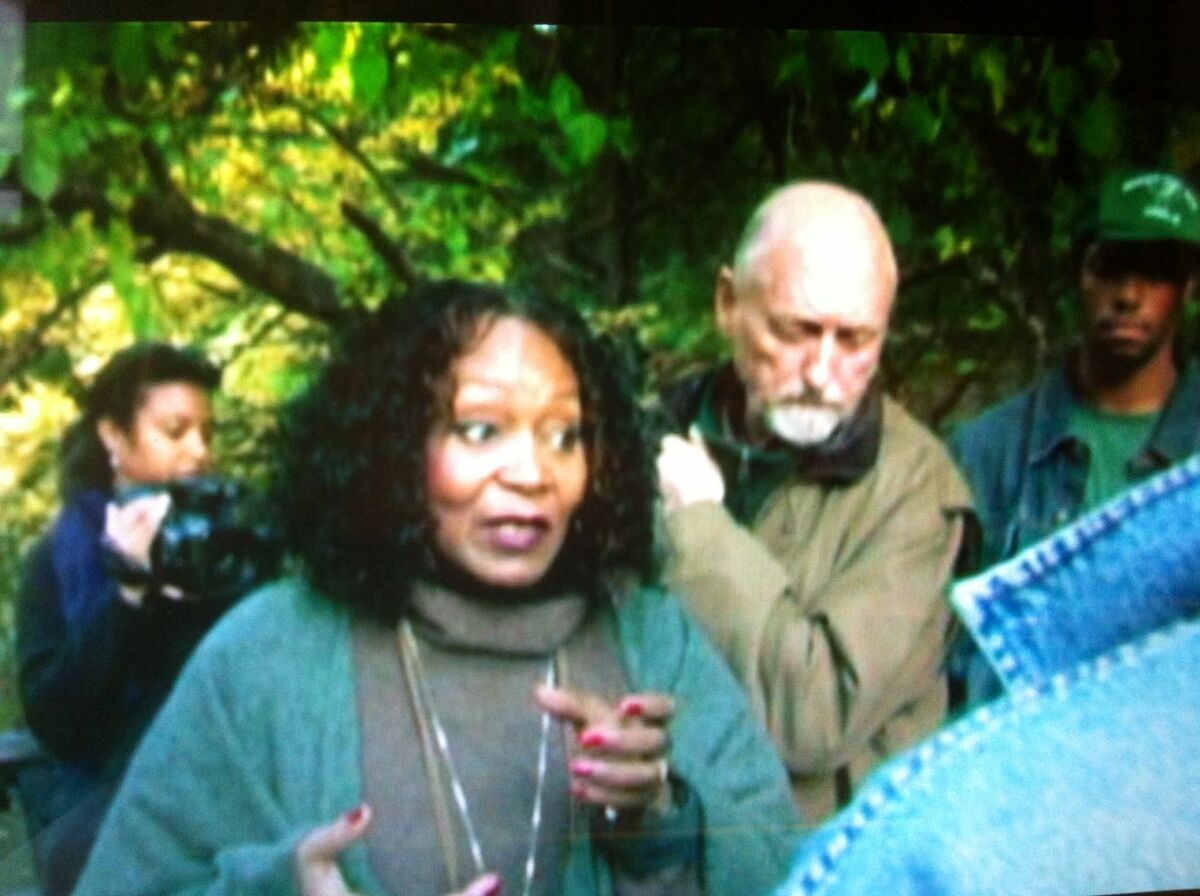

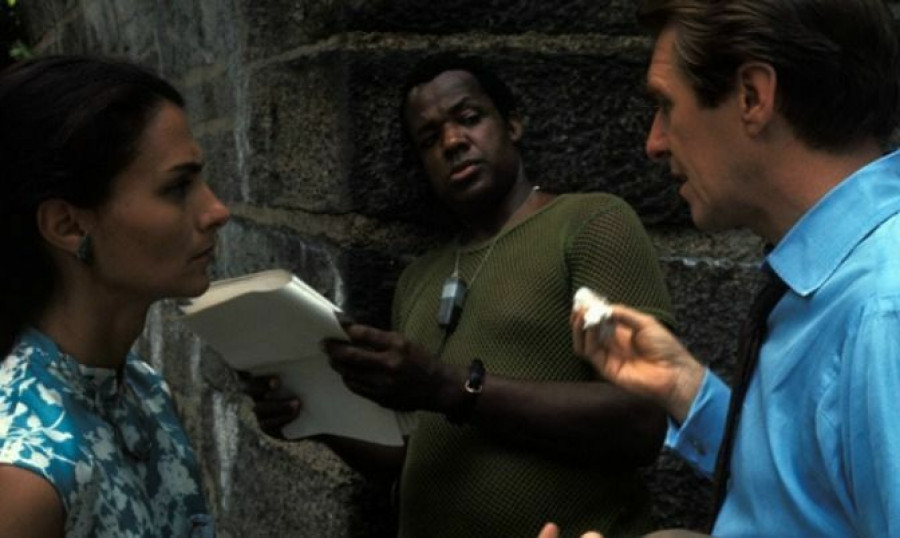

Bill wanted me to film scenes—steal scenes—in Central Park, showing the Fall and Winter seasons as we transitioned from one era to the next. Because before I knew it, I was bestowed the honor of assisting on Bill’s camera team for the highly anticipated sequel—some 35 years later—Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take 2 ½ executive produced by Steven Soderbergh and producer and additional cameraperson Steve Buscemi (we filmed on Panasonic AGDVX100s for the feature). Buscemi, our most recognizable star, would come to our Central Park set with a huge smile on his face and fully willing to go wherever Bill wanted to lead us. I and other crew members—new ones, such as fellow BDC members Henry Adebonojo and Jonathan Weaver, mixed in with crew from the original production—were clear on our assignment. We were to film ourselves as well as the throughline from Bill’s work with the actors on the first feature: An exploration of the craft of psychodrama. What exactly is psychodrama? I will leave that for at least one viewing of this film within a film, within a film to explain.

Both Symbios… have been reviewed as “entertaining, but somewhat hard to describe….” Sprinkle in “brilliant,” “bold,” “groundbreaking,” “the original reality show,” “not quite sure what it was supposed to be,” and you have summed up how much Bill Greaves marched to his own drummer. Both the original film and its sequel co-starring yours truly (in a tiny, somewhat embarrassingly foot-in-my-mouth role) are available through The Criterion Collection. And from what I was able to discern from the activity on set, expanding upon the methodical juxtaposed with the sometimes extremely relaxed work ethic, could be explained by the 11 years Bill lived and worked in 1950s Canada.

Director Allan Wargon (Mr. Piper, Salt Cod): “Bill turned up at the Film Board unannounced and uninvited. He wanted to get a job and they wouldn't give him one.” The year was 1952 and Bill Greaves moved to Canada on the advice of friends he met in Hollywood including Canadian Louis Applebaum (Academy Award-nominated composer, The Story of G.I. Joe). Wargon says, “Bill was very keen to come. He just arrived… no invitations. Quite remarkable.”

His colleagues in the United States told him about the National Film Board (NFB). Bill, born in Harlem during its historic Renaissance was an actor turned director, and sought out an apprenticeship with NFB in hopes of directing films for a steady paycheck. He moved to Ottawa on a whim, not knowing a soul. When he arrived at NFB, he was said to have been regulated to lowly jobs such as washing floors around the offices. He was living on no income for many months.

According to Wargon, Bill continued to be friendly and extremely charming. Wargon soon offered him a regular seat at the dinner table to help him out financially. All the while, Wargon was convinced the Film Board could do much more. He says, “I went to the director of production and said ‘Look the guy is working. You really have to hire him.’ So they did hire him and he was put on staff, and given quite menial jobs to do like splicing film. Oddly enough he said that was the happiest time of his life, splicing 35mm film.”

“They gave him worst possible job,” remembers Louise Greaves about her husband in the hotsplice lab. She recalls him finally making a paycheck that only amounted to $2700 per year. “He was so happy. He needed to survive. So it was a step in the door.”

Fellow NFB colleague Alvin Goldman (Eject at Low Level and Live, Camera on Labour Nos. 1- 4): “Bill had to do what every novice there had to do. He had to show that he could work as part of his group, keep his nose to the grindstone and work well with people even though you may not like some of them. Bill fit in very well within the unit he was working. I got the impression he didn’t have any enemies there, very very well liked. It was not the Deep South, he was working in Canada. We are a little different (laughs).”

Others may have considered Bill’s work in the editing room only slightly removed from doing the floors but Bill was eager to learn every aspect of filmmaking from the bottom up. And being that this was 1950s Canada, he was surrounding himself with how film—especially government produced film—was effectively used to influence its audience in the aftermath of war. Louise, born Louise Archambault in Montreal, points out “The government needed to explain to Canadian people why they were fighting Nazis and defending the mother country Great Britain. We were a part of the British Commonwealth. Unlike Americans, Canadians had no choice.” Louise believes her husband may have been the first non-Canadian to get a staff job at NFB of Canada.

But Bill’s true goal of directing film still seemed a ways off. Wargon recalls, “The powers that be were very reluctant to hire a Negro director. I guess they felt there would be repercussions with the people he would be directing. Well they finally did try it, and there were no repercussions.”

Bill is credited as director on many NFB films during his eight and a half year tenure, including High Arctic, Four Religions, Emergency Ward and many others. According to Louise, “Bill was the chief editor/director of Unit B. They were winning all the awards by doing creative, not propaganda. They were doing cinema verite before it was even talked about.” And, more importantly, Bill’s colleagues started to get to know how much experience he was bringing to the table.

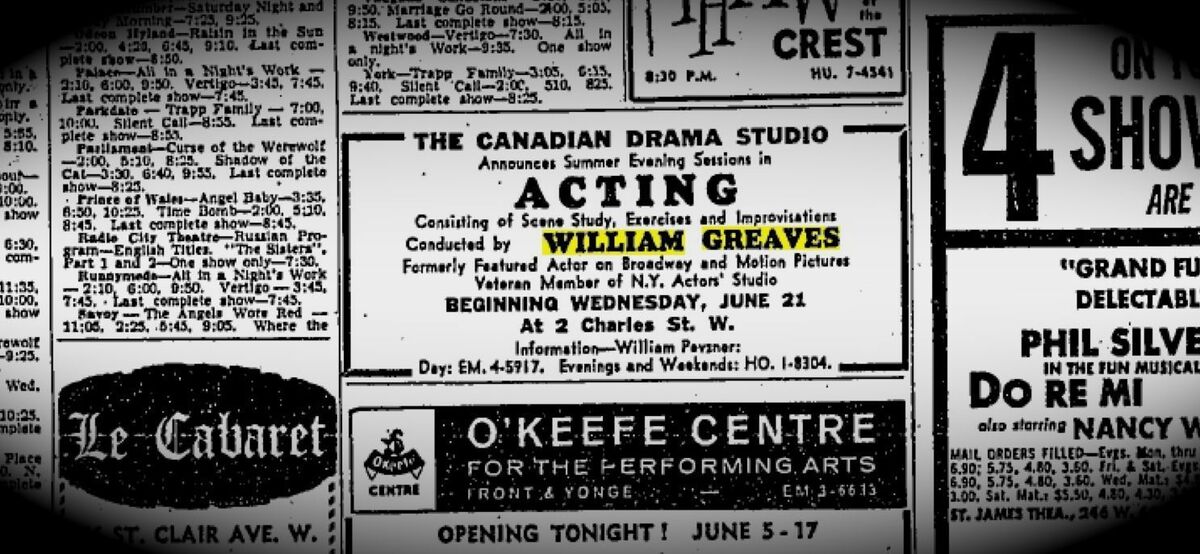

One of the resources Bill drew upon to set the tone for his films was his experience as a working actor. He had notable performances as a member of the reputable American Negro Theatre and was a member of the second class ever at New York’s famed Actor's Studio, which claims American ownership of Constantin Stanislavsky’s technique known as The Method. In speaking with all of those who had known Bill, no one in Canada’s acting community had ever been introduced to what some may call the “mumbling,” informal, and emotional memory style of Method acting. Louise remembers, “Directors at the Film Board were very curious... they continued picking his brain about The Method.” With a growing group of soon to be students, Bill realized he could make extra money. Thus, he launched weekend sessions of The Canadian Drama Studio in Ottawa and when NFB relocated to Montreal, the Studio relocated as well. The Canadian Drama Studio was their version of The Actors Studio.

“I just sort of discovered it when I was doing some research. I knew Greaves the documentary filmmaker, but then when doing research on Stanislavsky…” says editor Anna Migliarisi of the book About Directing, “…the history did not exist.” Her chapter, “The Method, Bill Greaves and Directing,” gives the essential chronology that holds Bill’s contribution to the Canadian talent pool up to the standard he required. “Whenever I can give a paper, I talk about Bill at conferences and inevitably people ask ‘Who is this man?’ I literally went through stacks of newspapers to find some stuff. And wasn’t he a handsome man?” Migliarisi felt committed, as herself an actress/director/historian/scholar to get the word out about the “intelligent, sharp and well-read Bill Greaves.” She said, “The more people I can introduce his work to I’m obliged and honored.”

It was the latter part of the 1950s and Montreal was known as homogenous in color, but harboring two distinct communities of English speakers on one end and French speakers on the other. But according to Migliarisi and echoed by actors in attendance of Bill’s classes, the studio “was a haven of diversity, openness and values that we honor as artists.”

Star of both Symbio films and long-time friend of Bill’s, Shannon Baker, recalls classes being held twice a week, with workshops continuing at the studio he established in Ottawa and others popping up in Toronto. “I was surprised that he accepted me. I never missed a class. He did challenging acting exercises that I later learned were what was called The Method. I was so excited to be learning the craft of acting.”

NFB’s Goldman ended up following Bill from their day job to becoming his assistant for the acting classes. Says Goldman, “What I learned from Bill was the opposite of what the French actors had learned from their teachers who go back to the turn of the early 20th century. We did a lot of improv. I learned the importance of not pretending when you’re acting a role, but actually living the role and what you could bring from it to make it real.” He continues, “And this was a great attraction to French-speaking actors, who were well-established by the way, right at the peak of their career. They felt something missing from their lives—gestures from the classical teaching and less emphasis on emotional involvement in characters they were portraying.”

Master classes with top New York instructors were an integral part of the studio experience, including a visit by the legendary Lee Strasberg at Bill’s invitation. Baker was in attendance: “Strasberg was very relaxed in Montreal and very supportive of Bill. He and Bill talked about the need for relaxation when performing. They both discussed the need for 'being in the moment' when performing 'being fully present.' Lee discussed the value of ‘the private moment' exercise as a way of tuning up the Actor’s instrument. They clearly respected each other very much.”

It is Greaves who is credited as bringing a soulful approach that seemed to revolutionize the art of acting in this region of the continent. Migliarisi uncovered a 1961 quote from an interview with Bill in the Toronto Star: “The actor who cannot bring his audiences into the life of the play is like a musician who cannot elicit sound from his instrument. A fiddle player may have bow work that is fabulous and his finger work may be impeccable. But if no sound comes out, what the hell?”

It was ultimately Bill Greaves the man, who impressed Baker’s recruit to the classes. “I told Louise that she must come and meet this man. She refused, saying he would never accept her. Six or seven months later she finally gave in and of course the rest is history.”

Louise, Bill’s future wife, had only known of him as the songwriter of one of her favorite recordings, “African Lullaby” on the B side of Eartha Kitt’s C’est Si Bon. Of the song Louise remembers, “He wrote it in English and Swahili. We’re talking about 1950. Not too many people were thinking about Africa at the time.” As Baker stated, his friend Louise did eventually accompany him to Bill’s Method-acting meetings. Louise recalls the following: “I went to the first audition... and I thought, I'll never pass an audition. But then he never asked anybody to do anything. He didn't have a ‘problem with talent’ issue. According to him we were all talented! Everybody had talent. See you all next Saturday. Everybody was in! I walked away and I said who is this guy? Taking willy nilly off the street? It was a very important lesson for me.”

Bill’s simple questions to prompt the actor such as "What were you working on?" and never criticizing the answers that came after, distinguished Bill from other acting coaches. “His question at the end of the session of ‘Do you feel that you achieved what you wanted to achieve?’ I also thought was very encouraging. You were never embarrassed or critiqued for what you failed to do. He would just ask ‘What do you want to do next time?’” Louise described it as a democratic class that thrived on Bill’s excitement with the artistry. And as a lifelong resident of Montreal, Louise felt she had never seen the amount of cultural interchange as she was witnessing in the student makeup of Bill’s class. Louise states, “In a French professional community here's a guy—a Black man—from New York who was teaching quite differently.” She came out of each session feeling an enormous amount of personal development as well.

Louise’s first class with Bill was in 1957. They married in 1959. The love story between the two went unnoticed by many in the class. Simply put as Bill later told Migliarisi of their romance, “She was just so beautiful. I had to ask her out.”

And that’s where we come back to my night having fallen asleep on the couch, waking up to the television on and seeing a handsome young Bill Greaves, a suave young Shannon Baker, a young dark-haired beautiful actress (“Is that Louise?” I’m sure I said out loud to no one else in the room) Louise Greaves and more Canadians and crew members from Bill’s past now on screen in this confusing yet wildly entertaining 1968 production of a bewildered and willing cast following the rambling bumbling “Do you feel that you achieved what you wanted to achieve?” direction from Bill in Central Park.

Later, on the set of the sequel with the cast and crew still willing to absorb the musings of this amazing film artist I had only known as a civil rights crusader, I was honored to have the front row seat for a mishmash of scene study, spontaneity, tension, relaxation, frustration and surprisingly poetic brand of storytelling. The genius of Bill Greaves was bringing together unpredictable combinations that ultimately filled the screen with real moments.

Our Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take 2 ½ producer and co-star Steve Buscemi: "One of my favorite films is Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One. I saw it at the Sundance Film Festival in 1992, was blown away by the filmmaking, and I couldn't believe this great American film had never been released! It was a privilege to know Bill Greaves and an honor to work with him on Take 2 1/2. He was truly inspiring and I will miss him dearly."

Bill Greaves, author of 100 songs, producer of more than 200 films, will be missed by his friends in Canada. According to Goldman, “He learned his craft superbly. He had his eyes set on the future, to become a filmmaker in the U.S.” Wargon agrees, “Clearly his mission was in the States, just using Canada as a training ground. He learned film quite thoroughly.”

Upon moving to New York in 1963 with Louise and by then a young daughter in tow, Bill reconnected with his Actors Studio family and was “discovered” by avant garde filmmaker Shirley Clarke. One of the films he screened for her was the NFB produced cinema verite-style Emergency Ward, which according to Louise, “pre-dates today’s hospital shows. Real doctors, real nurses. He was allowed total access. She saw it and said wait a minute. This guy’s good.” Clarke introduced Bill to George Stevens, Jr., the then head of the United States Information Agency. At the time the UN Film and Television Division was prepared to hire a director to do a film about international travel. Stevens said of Bill, “We need this kind of filmmaker.”

“Bill was way ahead of his time. He was my teacher and I am still learning from him,” says Louise. “He almost got sidetracked because life was so comfortable in Canada. He didn't feel the kind of scorn and racism that he encountered as a child. He was welcomed there. But he thought, ‘Do I go back and fight and possibly subject myself to this foolishness or do I stay here and be comfortable?’"

![[REVIEW] 'Black-ish' is Racist](/media/k2/items/cache/d985bd01090113d5c682cff917f71c98_S.jpg?t=20170411_011541)