Artist:

Megan Morgan

Project Timeframe:

Commenced March 2013, completed November 2013, pending book publication Spring 2015 with Inanna Publications, Toronto.

Exhibition:

Featured in Gallery 1313, Toronto

Artist Recognition:

Featured artist on Wondereur.com, February 2014

Nominated for the Scotiabank Photography award by Karen Carter, Executive Director of Heritage Toronto, 2014

Dr. Annie Smith Graduate Scholarship Recipient, November 2009

Canadian Women’s Art Association Award Recipient, 2007

Gallery 44 Outstanding Photography Student Award, 2006 & 2007

Behind-the-Scenes Footage: 2 minutes in my studio

In her work “Mary and Susanna” photographer and artist Megan Morgan has composed a series of four large photographs inspired by the true story of Mary Prince and Susanna Moodie, slave and relative of slave owner respectively. Morgan first became aware of their story upon attending a presentation of York University’s Dr. Andrea Medovarski and her paper, Roughing it in Bermuda.

The story of Mary Prince and Susanna Moodie began when they met while Prince was enslaved in England. Prince agreed to tell her story of slaevery to Moodie, who happened to be an author, and a relative of a slave owner.

The Bermuda-born Prince would resonate with artist Megan Morgan generations later as Morgan was also born in Bermuda and raised in Canada, where author Moodie would eventually resettle and share Prince’s story. “The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave” is Prince’s story as told to Moodie in her book Roughing It In The Bush: Life in Canada, a popular text in Canadian schools.

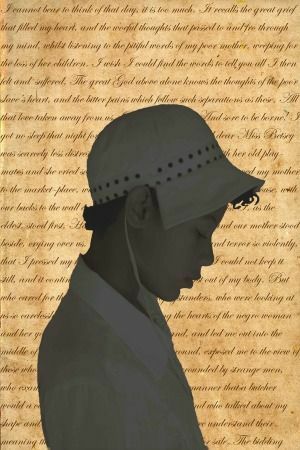

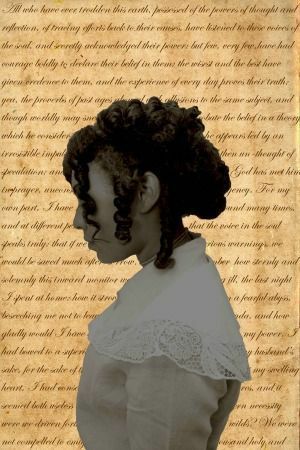

Morgan’s photography, set in the theme of hybridity, brought the pages of the book to life. The result: Two large photographs 24 x 28” and two, 26 x 32”, documenting this historical text on a very creative canvas.

Many documentarians working in historical film have struggled with acquiring archival footage when telling the stories of famous faces in history, mainly because of the exorbitant cost. A mere 30 seconds of film can range from hundreds to thousands of dollars. ‘Fair use’ acquisitions are free, but only after mounds of paperwork that involve legal and insurance professionals alike. What are filmmakers with a passion to tell the story of history makers to do?

Substitute images often make an appearance—such as recreations, title cards (text over a simple background), or other forms of representational footage. A bit more courageous is employing the work of visual artists like Morgan, who are just as inspired with the story.

“I immediately got the connection to Susanna Moodie’s Canadian canonical work as told in Roughing it in the Bush,” says artist Morgan. “But the autobiography of Mary Prince was published in an effort to help abolish slavery. A further reading of these two books opens up a window of new learning when you realize their connection. Were Moodie’s further Canadian pioneering recorded adventures influenced by this meeting? If so, in what ways? This very question challenges the notion of what it means to be Canadian. Further, this invites the question of what it means to be a Black Canadian.”

The strategic placement of two racially ambiguous women as an overlay to their handwritten texts are the images that really grab an observer’s attention. By photographing two actresses in this vein, Morgan takes away the influence of black and white--and therefore race in this unlikely partnership--and chooses to focus on their conversation instead. 'We Say to Each Other and to You’ is a photograph of the two women (represented by young women that I asked to play them as characters). In this photograph they are slightly silhouetted and facing one another. The words they wrote float behind them,” says Morgan.

She builds on this with the following panel: “There are of course no actual photos of Mary Prince due to the invention of photography not having been discovered during that time. ‘Mary and Susanna’ is a photo of the two characters facing the viewer. In this photo I am asking you directly to question what you are seeing and what you thought you knew about these two women before now. Each has a story to tell, what will you learn and discover about yourself, your history and your part in all of this?”

As a multidisciplinary artist who focuses primarily on photography, Morgan incorporates video, textile construction, installation and performance. “Hybridity in its many forms interests me,” she says. “Race, like gender and fabric is a form of camouflage. It covers and defines the body. It is not static. It is categorical and at the same time manages to erase and speak for identity; it is flawed. My work investigates the complexities and constraints involved when discussing the subject of race, gender and family history; the very things that inform identification.”

Morgan grew up in Canada having been adopted by her white grandparents upon her parents’ death. Her hybrid style resonates with her upbringing she says: “I’m seen as Black and claim Black identity. In Canada we don’t talk about race very much. But it became a conversation once I got into school. And, even though my grandparents did the best they could, I had a very naïve point of view.”

As an adult Morgan went in search of her father’s side of the family—the closest she could get to the story of her African roots. “My work has come from exploring what the world means to me and others…a unique perspective, in that I’m aware of who I am and what I look like, but missing vital pieces,” says Morgan. “I had contact with my father’s family, even though I was never allowed contact before. All is good now but I had to personally seek them out.”

As an artist, Morgan connects to her sense of self by diving into painting, performance, and photography, noting that for her “the camera is the most powerful tool.”

For her interpretation of the “Mary and Susanna” story, Morgan photographed and enlarged excerpts from the text that she says were a turning point in the lives of both women. “Both were both torn away from something,” she reflects. “Susanna Moodie arrived as an emigrant following her husband’s wishes to move to Canada and Mary Prince was taken by her mother to be sold on the auction block.”

Screen grabs from the text read as follows:

Mary:

“We followed my Mother to the market place where she placed us in a row against a large house with our backs to the wall and our arms folded across our breasts. I, as the eldest stood next to Hannah next to me, then Dinah; and our mother stood beside, crying over us.

My heart throbbed with grief and terror so violent that I pressed my hands tightly across my breast, but I could not be still and it continued to leap as though it would burst out of my chest.

But who cared for that? Did one of the many bystanders who were looking at us so carelessly, think of the pain that wrung the heart of a negro woman and her young ones?”

Susanna:

“Well do I remember how sternly and solemnly this forward monitor warned me of approaching ill, the last night.

I spent it at home: how it strove to draw me back as from a fearful abyss, beseeching me not to leave England and emigrate to Canada, and how gladly would I have obeyed the injunction had it still been in my power.

I had bowed to a superior mandate, the command of duty: for my husband’s sake, for the sake of the infant, whose little bosom heaved against my swelling heart.

I had presented to bid adieu forever to my native shores, and it seemed both useless and sinful to draw back. Yet, by what stern necessity were we driven forth to a new home amid the western wilds?”

“Although there exist several scholarly papers on this subject, this is not something that the general public even has a clue exists,” says Morgan. “Yet, as Canadians we are all familiar with Susanna Moodie’s work and we learn about the Underground Railroad in Canada in schools, but there is so much more to our complicated history than that.”

Morgan collaborated with Dr. Medovarski on the research. Yet her passion to bring this story to contemporary audiences in her unique storytelling style stem from her personal history as a Bermuda native whose travels attempted to dictate her identity: “My concerns have a psychological orientation. The only way to reconstitute yourself when you have been consistently misidentified is to confront subjectivity and perhaps even become the very ‘thing’ that objectifies and categorizes you. My aims seek an in depth look at the parameters, definitions and constructs of identity.”

And what does Morgan hope will be a takeaway for those who see this work? “Our notion of history and representation is inordinately skewed to privilege the dominant culture, but all of our stories are important. I thought this was the perfect opportunity to bring history, culture, literature and even feminism into the spotlight.”

Morgan will have related work featured in Harvard University Press with an essay by Dr. Deborah Willis in the Journal, The Image of the Black in Western Art, Volume V Part II, October 31, 2014. She was also the featured artist on Wondereur.com, February 2014 and was nominated for the Scotiabank Photography award by Karen Carter, Executive Director of Heritage Toronto, 2014.

![[REVIEW] 'Black-ish' is Racist](/media/k2/items/cache/d985bd01090113d5c682cff917f71c98_S.jpg?t=20170411_011541)