For 15 long minutes, I held my breath, trying not to panic. It was only after my husband called me back that I dared to breathe again. Everything was fine. It was just a broken taillight on the rental car.

Listen to the audio version of this article:

This incident was a few years before Sandra Bland died in police custody after being stopped for a similar traffic violation, but by then I’d already learned that something as small and harmless as a cell phone, a wallet, or a loose cigarette could be deadly for Black people interacting with police.

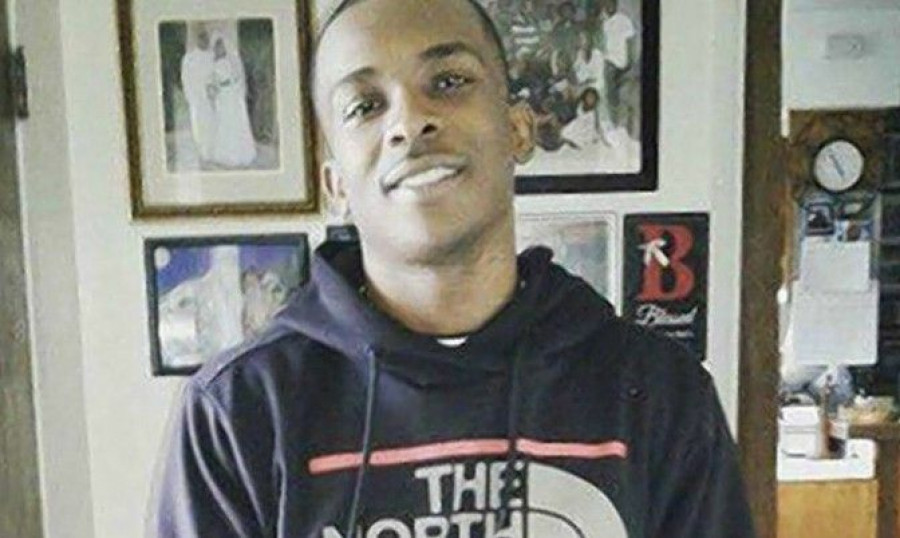

So, when Stephon Clark was shot and killed by officers just a few weeks ago with nothing in his hands but a phone, I was heartbroken, but not surprised. Clark has joined the long list of Black men and women killed by police and memorialized by hashtags and protests.

As I wrangled with the feelings of rage and frustration at the injustice of Stephon Clark’s death, I learned something that gave me pause: he was an anti-black misogynist, and he was not shy about it. His Twitter account is littered with tweets like, “Dark women bring dark days,” and “Black bitches <<<<<< I don’t want nothing Black but a Xbox.”

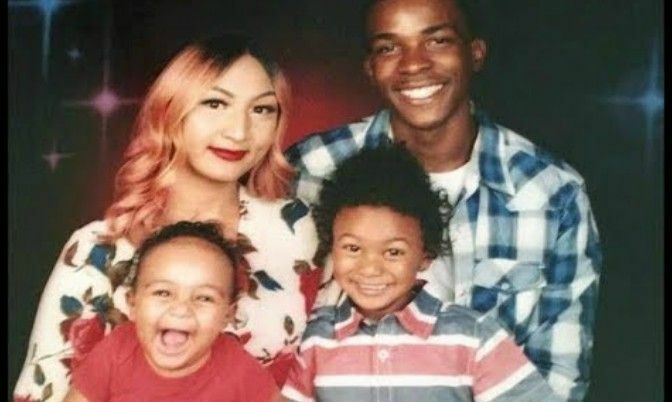

Stephon Clark with his fiancee and two children.

Clark’s sentiments are neither original nor rare. I have read words like those from other young men like him more times than I can count. I’ve seen Black women called roaches, bed wenches, bitter, ugly, and every kind of derogatory term you can imagine. Misogynoir—misogyny targeted specifically at Black women—is so commonplace that it’s hardly shocking.

And while it is infuriating, I’ve personally learned to push my rage aside simply because I cannot afford to be angry all the time.

But reading Stephon Clark’s hateful words in the wake of his death has brought that anger back to the surface. His misogynoir has made defending him difficult. Not because he deserved to die. He did not. As foul and harmful as misogynoir may be, it is not a crime punishable by death. Stephon Clark should be alive. His death was an injustice. It is terrible that his children must live without him, that his mother must bury her child, that all his dreams and aspirations will never be fulfilled.

No, the conflict comes from what defending him costs us. We are forced to reconcile the fact that we are standing up for a man who felt comfortable putting us down, degrading black womens bodies. We are forced to compartmentalize the pain of misogynoir and the injustice of state violence, even as the two intersect. We are forced to consider if, while still alive, Stephon Clark ever knew (or cared) that Black women have been the ones to lead the charge for justice, marching in the streets and creating movements like Black Lives Matter.

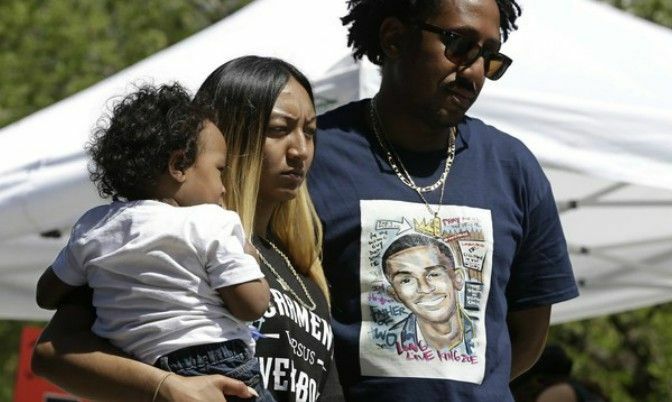

Stephon Clark’s fiancee Salena Manni, holds the couple's son, Aiden as she and Clark's uncle, Curtis Gordon attend a rally. (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli)

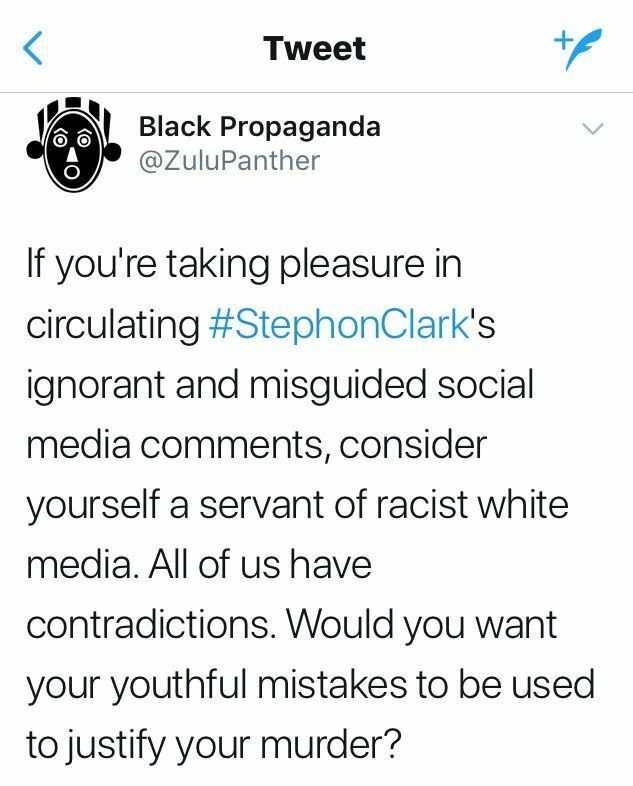

The weight of this conflict is heavy, and it is being made heavier by the reality that we are being unfairly judged for it. Many Black women have spoken out about their feelings on Stephon Clark, and the response from Black men has been incredibly disappointing. They have crept into the comment sections of Black women’s Facebook statuses, tweets, and online articles to tell us that Clark’s misogynoir should not matter. Black women have been accused of being bitter, of centring ourselves, of engaging in character assassination and justifying Clark’s death. We have been compared to media outlets who shared photos of Trayvon Martin showing the middle finger or dug up Philando Castile’s traffic-related charges.

They’ve wrapped their reprimand in the shroud of, “Don’t speak ill of the dead.” They do not see how their approach speaks volumes about them. Black men who refuse to give Black women space to feel angry about Stephon Clark’s misogyny show that the only justice that matters to them is the kind they benefit from. They reduce Black women to emotional mules who should cry for them as we ignore our own pain. They ask us for solidarity without a single thought to how they could stand beside us too.

A tearful Sequita Thompson, center, discusses the shooting of her grandson, Stephon Clark, during a news conference. (Rich Pedroncelli / Associated Press)

Their attitude is a reminder that as Black women, we live in the intersection between Blackness and womanhood—quite literally between a rock and a hard place—and we do not have the privilege of prioritizing state violence as our main battlefield. For us, the fight for safety and justice has to be more holistic than that. It must also include standing up against things like misogyny, sexual assault, and domestic violence, often at the hands of Black men.

A house divided against itself cannot stand. And as long as Black men continue to ask Black women to be silent about the ways they harm us, our community will remain fractured. Stephon Clark’s death and the discovery of his misogyny is heartbreaking, but it is also a valuable opportunity for Black men to close the gap and heal the wounds Black women have been suffering since the Civil Rights era.

It is a chance for them to check their misogynoir, to call their brothers higher, to defend Black women from other Black men who devalue and belittle us. It is time that they acknowledge that we can and must fix the injustices within the Black community even as we battle fiercely for justice from those outside of it.

Talia Leacock-Campbell is passionate about helping women tell their stories and speak their truth as a copywriter for small businesses and personal brands and ghostwriter to CEOs eager to establish their expertise through writing. Other than a laptop and a story to tell, the keys to her heart: seafood, literature, and killer shoes.

By

By